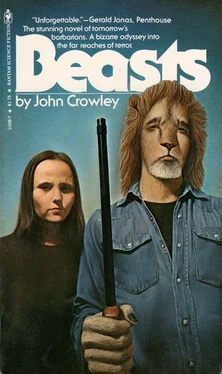

John Crowley - Beasts

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Crowley - Beasts» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1978, ISBN: 1978, Издательство: Bantam Books, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Beasts

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bantam Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1978

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0553111026

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beasts: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Beasts»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Every hand is raised against the half-human, half-animal mutants who roam the desolate frontier. The lost, predatory creatures men call

BEASTS

Beasts — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Beasts», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Some days later. Flying home from the margins of the gray sea, weary, talons empty. From a great height he saw the man moving with difficulty over the marshy ground: followed his movements with annoyance. Men caused the world to be still, seek cover, lie motionless, swamp-colored and unhuntable, for a wide circle around themselves: some power they had. The man looked up at him, shading his eyes.

Loren stopped to watch the hawk fall away diagonally through the air as cleanly and swiftly as a thrown knife. When he could see him no longer, he went on, his boots caught in the cold, sucking mud. He felt refreshed, almost elated. That had been a peregrine: it had to be one of his. At least one bird of his had lived. It seemed like a sign. He doubted he would ever read its meaning, but it was a sign.

The tower seemed deserted. There was no activity, no sign of habitation. It seemed somehow pregnant, waiting, watching him; but it always had, this was its customary expression. Then his heart swelled painfully. A tall, bearded boy came from the tower door, and saw him. He stopped, watching him, but didn’t signal. Loren, summoning every ounce of calm strength he owned, made his legs work.

As he walked toward Sten, an odd thing happened. The boy he had carried so far, the Sten who had inhabited his solitude, the blond child whose eyes were full of promise sometimes, trust sometimes, contempt and bitter reproof most times, departed from him. The shy eyes that met his now when he came into the tower yard didn’t reflect him; they looked out from Sten’s real true otherness and actuality, and annihilated in a long instant the other Sten, the Sten whom Loren had invented. With relief and trepidation, he saw that the boy before him was a stranger. Loren wouldn’t embrace him, or forgive him, or be forgiven by him. All that had been a dream, congress with phantoms. He would have to offer his hand, simply. He would have to smile. He would have to begin by saying hello .

“Hello,” he said. “Hello, Sten.”

“Hello, Loren. I hoped you’d come.”

So they talked there in the tower yard. Someone seeing them there, looking down from a height, would not have heard what they said, and what they said wasn’t important, only that they spoke, began the human call-and-response, the common stichomythy of strangers meeting, beginning to learn each other. In fact they talked about the hawk that floated far up, a black mark against the clouds.

“Could it be one you brought in, Loren?”

“I think it must be.”

“We can watch it and see.”

“I doubt if I could tell. They weren’t banded.”

“Could it be Hawk?”

“Hawk? I don’t think so. No, That would be… That wouldn’t be likely. Would it.”

A silence fell. They would fall often, for a while. Loren looked away from the blond boy, whose new face had already begun to grow poignantly familiar to him, terribly real, He ran his hand through his black hair, cleared his throat, smiled; he scuffed the dead grass beneath his feet. His heart, so long and painfully engorged, so long out of his body, began to return to him, scarred but whole.

Painter lay full length on his pallet at the dark end of the building Loren had once lived in, The cell heater near him lit his strange shape vaguely. He lifted his heavy head when they came in, easeful, careful. If he had been observing them in the tower yard he gave no sign of it.

“A friend,” Sten said. “His name is Loren Casaubon. My best friend. He’s come to help.”

The leo gazed at him a long time without speaking, and Loren allowed himself to be studied. He had often stood so, patiently, while some creature studied him, tried to make him out; it neither embarrassed nor provoked him. He stared back, beginning to learn the leo, fascinated by what he could see of his anatomy, inhaling his odor even as the leo inhaled his, Half-man, half-lion, the magazines and television always said. But Loren knew better, knew there are no such things as half-beasts: Painter was not half-anything, but wholly leo, as complete as a rose or a deer. An amazing thing for life to have thrown up; using man’s ceaseless curiosity and ingenuity, life had squared its own evolution. He almost laughed. Certainly he smiled: a grin of amazement and pure pleasure. The leo was, however he had come about, a beautiful animal.

Painter rose up. His prison weakness had not quite left him; now, when he stood, a sudden blackness obtruded between him and the man who stood before him. For a brief moment he knew nothing; then found himself supported by Sten and Loren,

“Why did you come here?” he said.

“Reynard sent me. To help Sten.”

The leo released himself from them. “Can you hunt?”

“Yes.”

“Can you use those?” He pointed to Loren’s old rabbit wires hung in a corner.

“I made them,” Loren said.

“We’ll live, then,” Painter said. He went to where the snares were hung and lifted them in his thick graceless fingers. Traps. Men were good at those.

“Can you teach me?” he asked.

“Teach you to be a trapper?” Loren smiled. “I think so.”

“Good.” He looked at the two humans, who suddenly seemed far away, as though he looked down on them from a height.

Since the moment in the dead city when he had seen that there was no escape from men, no place where their minds and plans and fingers couldn’t reach, a flame had seemed to start within him, a flame that was like a purpose, or a goal, but that seemed to exist within him independently of himself. It was in him but not of him. It had nearly guttered in the black prison, but it had flamed up brightly again when he had taken the man Barron in his grip. In the days he had lain with Caddie on the pallet here in the darkness he had begun to discern its shape. It was larger than he was; he was a portal for it only. Now when he looked at the men and saw them grow small and far-off, it flared up hotly, so hotly that it blew open the doors of his mouth, and he said to them, not quite knowing why or what he meant: “Make me a trapper. I will make you hunters of men.”

Furious, Hawk broke his stoop and with a shriek of bitter rage flung himself toward the prongs of a dead tree. The rabbit struggling on the ground, hurt, helpless, had been the first edible creature he had seen all day. And just as he was diving to it with immense certainty, already tasting it, the big blond one had stamped out of the weeds with a shout.

Hawk observed the intruder mantle over the rabbit. He roused, and his beak opened with frustrated desire. They were driving him off: from his home, from his livelihood. The wind, too, pressed him to go, creeping within his plated feathers and causing the ancient tree to creak. Unknown to him, a family of squirrels lay curled inside the tree, not far below where he sat, utterly still, nosing him, alert with fear. Hawk didn’t see the squirrels: there were no squirrels there.

Painter slit the twitching rabbit’s throat neatly and then attempted to take it from the snare. He knew he must think, not pull. There was a plan to this. His unclever fingers moved with slow patience along the wire. He could learn this. He suggested that the man within him take a part: help him here.

He gutted the rabbit, and slit its ankle at the tendon; then he slipped one foot through the slit he had made so that the rabbit could be carried. The hitch was neat, satisfying, clever. He wouldn’t have thought of it: the boy Sten had shown it to him.

The long prison weakness was sloughing away from him; and even as his old strengths were knitting up in him, cables tempered somehow by loss, by imprisonment, he felt his being knitted together too, knitted into a new shape. Carrying the rabbit, enjoying the small triumph of the snare, he went up a low hill that gave him a view over the wide marshland. The feeble sunlight warmed him. He thought of his wives, far off somewhere; he thought of his dead son. He didn’t think anything about them; he came to no conclusions. He only thought of them. The thoughts filled him up as a vessel, and passed from him. He was emptied. Wind blew through him. Wind rushed through him, bright wind. Something brilliant, cold, utterly new filled him as with clear water. He knew, with a certainty as sudden as a wave, that he stood at the center of the universe. Somehow — by chance even, perhaps, probably, it didn’t matter — he had come to stand there, be there, be himself that center. He looked far over the winter-brown world, but farsighted as he was he couldn’t make out the shape of what lay at his frontiers, and didn’t attempt to. From all directions it would come to him. He thought: if I were raised up to a high place, I would draw all men to me.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Beasts»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Beasts» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Beasts» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.