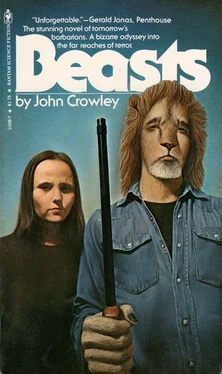

John Crowley - Beasts

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Crowley - Beasts» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1978, ISBN: 1978, Издательство: Bantam Books, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Beasts

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bantam Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1978

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0553111026

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beasts: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Beasts»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Every hand is raised against the half-human, half-animal mutants who roam the desolate frontier. The lost, predatory creatures men call

BEASTS

Beasts — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Beasts», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Very soon he would start south. His children had already departed, and he saw his wife less and less often as she scouted farther south. That evening she would not return; and soon winter would pinch him deeply enough to start him too toward the warmth. He lingered because he was ignorant; he had never made the journey, didn’t know from repetition that the summons he felt was that summons. His first winter he had spent in the warmth of an old farmhouse; the second he had been flung into late, and he had only managed, mad with molt and cold and near-starvation, to come this far before spring saved him.

Returning at evening to the empty tower over the brown and suddenly unpopulated marshes, he had seen the big blond one arrive on foot; watched him tentatively explore the place. Then he slept. Men were of little interest to Hawk, though they didn’t frighten him; he had lived much in their company. The following day another arrived, smaller, dark. The first visitor pointed Hawk out to the second where he stood on the tower top. Hawk went off hunting, deeply restless, and caught nothing all day. He stood sleepless long into the night, feeling the pressure of the wheeling stars on his alertness.

Below him in the shed, Caddie pressed herself against Painter, squirmed against him as though trying to work herself within the solidity of his flesh; tears of relief and purgation burned her eyes and made her tremble. She stopped her ears, too full of horrors, with the deep, continual burr of his breath, pressed her wet face against the drum of his chest. She wanted to hear, smell, touch, know nothing else now forever.

The next morning she was awakened by the growing burr of an engine. Painter was awake and poised beside her. She thought for a moment that she was in Reynard’s cabin in the woods, where in her dream she had been sleeping. The engine came close — a small motor-bike, no, two. Painter with silent grace rose, stepped to the boarded window, and peered through the slats.

“Two,” he said. “A blond boy. A dark girl.”

“Sten,” Caddie said. “Sten and Mika!”

She rose, laughing with relief. Painter, uncertain, looked from her to the door when it opened. Morning light silhouetted the bearded youth for a moment.

“Sten,” Caddie said. “It’s all right.”

Sten entered cautiously, watching Painter, who watched him. “Where’s Reynard?” he said quietly.

Painter said: “Shut the door.”

Mika slipped in behind Sten, and Sten shut the door, The leo sat, slowly, without wasted motion, reminding Sten of an Arab chief taking a royal seat on the rug of his tent. The room was dim, tigered by bars of winter sunlight coming in through holes in the boarded windows, spaces in the old walls.

“You’re Painter,” Sten said. The leo’s eyes seemed to gather in all the light there was in the room, to glow in his big head like gems cut cabochon. They were incurious.

“All right,” he said.

“We thought you were dead,” Mika said.

“I was.” He said it simply.

“Why did you come here?” Sten said. “Did Reynard… How did you get away from them?” He looked from the leo to the girl, who looked away. “Where is Reynard? Why are you here and not him?”

“Reynard is dead,” Caddie whispered, not looking up.

“Dead? How do you know?”

“She knows,” Painter said, “because she killed him.”

Caddie’s face was in her hands. Sten said nothing, unable to think of the question that would make sense of this.

Eyes still covered, unwilling to look at them, Caddie told them what had happened; she told them about the capital, about the hospital, the bearded man, tonelessly, as though it had happened to someone else. “He made me,” she said at last, looking up at them. “He made me do it. He said there was no other way of getting Painter free except to trade him for you, Sten. And there was no way he could keep from telling all he knew about you unless he was dead. So we planned it. We made a distraction at the hospital — the crowd — so Painter could get away. He said it was the only way.” She pleaded with them silently. “He said he longed for it. He said, ‘Do it right; do it well.’ Oh, Jesus…”

Mika came to her and sat beside her, put her arm around her, moved to pity. Horrible. She thought Caddie would weep, but she didn’t; her eyes were big, dark, and liquid as an animal’s, but dry. She took Mika’s hand, accepted absently her comfort, but was uncomforted.

No one spoke. Her brother sat down warily opposite Painter. Mika felt, in spite of the golden, steady regard in the leo’s eyes, that he saw nothing, or saw something not present, as though he were a great still ghost. What on earth was to become of them? They lived at the direction of beasts. Reynard had used Caddie as he might a gun he put into his mouth. In the mountains with the leos she had witnessed inexplicable things. Now in the shuttered shack she felt intensely the alien horror that Reynard had inspired in her the first time she had seen him; the same horror and wrongness she felt when she thought of certain sexual acts, or terrible cruelties, or death.

“He sent us both here,” Sten said softly to the leo. “He must have meant for us to meet.” He raised his head, tightened his jaw in a gesture Mika knew meant he was uncertain, and wanted it not to show. “It’s my plan, when things are — further along, to protect you. All of you. To offer you my protection.”

Mika bit her lip, It was the wrong thing to say. The leo didn’t stir, but the charge that ran between him and her brother increased palpably. “Protect yourself,” he said. Then nothing more.

They were engaged in some huge combat here, Mika felt, but whether against the leo or beside him, and for what result, she didn’t know, And the only creature who could resolve it for them was dead.

There are bright senses and dark senses. The bright senses, sight and hearing, make a world patent and ordered, a world of reason, fragile but lucid, The dark senses, smell and taste and touch, create a world of felt wisdom, without a plot, unarticulated but certain.

In the hawk, the bright senses predominated. His scalpel vision, wide and exact and brilliantly hued, gave him the world as a plan, a geography, at once and entire, without secrets, a world that night (or — in his youth — the hood) annihilated utterly and day recreated in its entirety.

The dog made little distinction between day and night. His vision, short-sighted and blind to color, created not so much a world as a confusion, which must be discounted; it only alerted him to things that his nose must discover the truth about.

The hawk, hovering effortlessly — the merest wing shift kept him stable above the smooth-pouring, endlessly varied earth — perceived the dog, but was not himself perceived. The dog held little interest for him, except insofar as anything that moved beneath him had interest. He recorded the dog and its lineaments. He included the dog. He paid him no attention. He knew what he sought: blackbird on a reed there, epaulet of red. He banked minutely, falling behind the blackbird’s half circle of sight, considering how best to fall on him.

Through a universe of odors mingled yet precise, odors of distinct size and shape, yet not discrete, not discontinuous, always evolving, growing old, dying, fresh again, the dog Sweets searched for one odor always. It needed to be only one part in millions for him to perceive it; a single molecule of it among ambient others could alert his nose. Molecule by molecule he had spun, with limitless patience and utter attention, the beginnings of a thread.

The thread had grown tenuous, nearly nonexistent at times; there were times he thought he had lost it altogether. When that happened, he would move on, or back, restless and at a loss until he found it again. His pack, not knowing what he sought or why, but living at his convenience — usually without argument — followed him when he followed the thread of that odor. Somewhere, miles perhaps, behind him, they followed; he had left a clear trail; but he had hurried ahead, searching madly, because at last, after a year, the thread had begun to thicken and grow strong, was a cord, was a rope tugging at him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Beasts»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Beasts» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Beasts» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.