The fox came to him in prison. He thought at first he had invented him too. Not a prison like this one: white, naked, without surfaces, only the cryings-out of steel doors shrieking closed together. Get you out of here. What did he want? Nothing. Out of there: away from darkness, through the shrieking doors, into Sun’s face again. Why?

Accept it as your due, the fox had said. Only accept it. You deserve my service; only accept it.

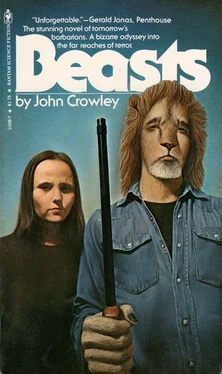

“Painter,” said the fox.

Take me as your servant, he had said. Only go by my direction for a while. For a long while, maybe. Take what you deserve; I’ll point it out to you.

“Painter,” said the fox.

If this were the fox before him now in the black prison, he would kill him. The fox had betrayed him, freed him from the white prison so that he could die in the black; had given him over to the men. Had killed his son.

Would kill him. Sun alone knew why he wanted such deaths. And if this were the fox.

“Painter.”

before him now he would

“Your servant,” said the fox.

“You.”

“I’ve come to get you out. Again.”

“You put me here.” His long-unused voice was thick.

“An error. A piece of planning that went badly. My apologies. It’s worked out for the best.”

“My son is dead.”

“I’m sorry.”

Painter moved his arms against the shackles. Reynard, hardly taller than he, though he stood, bent over him, leaning on his stick. “How ill are you?”

“I could still kill you.”

“Listen to me now. You must listen. There is a way out of this.”

“Why? Why listen?”

“Because,” Reynard said, “you have no one else.”

From the window of the consulting room, Barron looked down on them. Like a scene from some antique cartoon or fairytale, seeing them together. Hideous, in a way. Misdirected ingenuity. Frankenstein. He wondered at the fox, though; had he been right, about his own nature? It would be interesting to see what limits there were to his intelligence. Certainly he was cunning, cold, in a way no man could be; but still he apparently had been unable to see that the price he had asked for his betrayal was too high, and that to leave him in peace was something the government couldn’t possibly do. Once Reynard was of no more use to them, he certainly couldn’t be set free to do more mischief.

Tests, maybe. It would be interesting to see. A misdirected experiment, perhaps, and yet perhaps something could be leamed from it.

What were they saying? He cursed himself for not having forseen this, not having the courtyard bugged.

In the morning, Caddie found a food shop and ate, pressed in among other bodies, watching the windows steam up and the steam condense to tears that streaked the panes. An argument started and threatened to become a fight. Everyone here seemed touchy, frustrated, at flashpoint. What did they want so badly, which they weren’t getting? What was it that goaded them?

She began her circuit of the park again, carefully studying faces and places, wondering what she could do alone, if she couldn’t find Reynard. Nothing. She had no idea where Painter was. Government channels are silent . But she couldn’t give up, not after having come so far, counted so much on this plan, readied herself so carefully for any sacrifice…. She found that she was hurrying, not searching, driven by anxiety. She stopped, and closed her eyes. No hope, she must have no hope. When her heart was calm, she opened her eyes. At an intersection of streets not far off was a slim, black three-wheeler, closed and faceless.

She approached it by stages, uncertain, and not wanting to reveal herself. When she passed by it, walking aimlessly and not looking at it, as though passing by chance, the passenger door was pushed open by a stick. “Get in,” Reynard whispered.

His traveling den smelled richly of him, though he himself was obscure in the shuttered darkness. The man up front was uniformed. Caddie looked from him to Reynard, uncertain.

“My jailer,” Reynard said. His harsh sandpaper voice was fainter than ever. “On our side, though. More or less.”

Still not knowing how freely she could speak, Caddie gave him the paper the bearded man had given her. She saw Reynard’s spectacles glint as he bent over it, his nose almost touching it. He folded it, thoughtful.

“It’s Meric Landseer who’s done this,” he said at last. “Yes. His tapes. Prepare ye the way of the Lord. Well. It’ll do. Yes.” He put the paper back in her hand, and leaned close to her, seizing her wrist in the strong, childlike grip she had first felt in the woods, in the hollow tree. “Now listen to me and remember everything I say. I’m going to tell you where Painter is. I’m going to tell you what he must do to be free, and what the price is, and what you must do. Remember everything.”

When he had told her, though, she refused. He said nothing, only waited for her answer. She felt she would weep. “I can’t.” she said.

“You must.” He stirred, impatient or uncomfortable. “We don’t have time here to talk. If I’m missed, they’ll suspect something. They’ll prevent this. Now I’ll tell you: it was I who sent the Federals to the Preserve, to arrest Painter, Do you understand? Because of me he’s where he is. He might have died. He will die, now, if he’s not freed. His son. I murdered him. By what I did. Do you understand? All my fault. You might have starved. His wives and children. All my fault. Do you understand?”

He had taken her wrist again, and squeezed insistently. She looked at his black shape, feeling well up in her a disgust so deep that saliva gathered in her mouth, as though she would spit at him. Alien, horrid, as unfeeling as a spider. She wanted desperately to leave, to do this without him, but she knew she couldn’t. “All right,” she said thickly.

“You’ll do it.”

“Yes.”

“Exactly as I said.”

“Yes.”

“Remember everything.”

“Yes.” She pulled her wrist from his fingers. He pushed open the door with his stick.

“Go,” he said.

She went across the street to the park, pulling up her jacket collar against the cold wind, which blew papers and filth against her ankles as she walked. She wouldn’t weep. She’d think of Painter and Painter’s son only. As though she were an extension of the gun and not the reverse, she would execute its purposes. She wouldn’t think .

The pillared shrine contained only an enormous seated figure Caddie thought she should know but couldn’t remember. His name, most of his left leg, and some fingers had been erased by a bomb. The black rays of the blast still flashed up the pillars and across the walls as though frozen at the moment of ignition. The same desperate and illegible slogans marked this monument, sprayed across the slogans cut in stone. With malice toward none, and justice for all.

Vengeance.

At the side of the building the bearded man sat on the steps, eating hard-boiled eggs from a paper and talking animatedly to a group of men and women gathered around him. The step was littered with eggshell and his beard was flecked with yolk.

“Brutality,” he was saying. “What does that mean? It doesn’t matter what they do. Their morality isn’t ours, it can’t be. It’s enough that we see the right in our terms, and if we see it we must act on it. The basis of all political action…”

He turned and looked at her, munching. She gave him back the paper he had given her, with the picture of the leo on it.

“I know where he is,” she said.

“Without the shackles,” Reynard said.

“We can’t,” Barron said. “How do we know what he’ll do?”

“A crowd of people is outside,” Reynard said. “They’ve been waiting all night. Do you want them to see him shackled?”

Читать дальше