Admittedly Richard did have one thing in common with all the memoirists of the postwar period: He too was never in the war, in the trenches. First they sieved out the tubercular ones — the hunchbacks’ turn was still to come. But if one happened to ask Richard with a show of surprise why his number hadn’t yet come up, he bent down over the table and breathed his secret: “You know — just between you and me — I’ve got— flat feet. . .”

I still remember the painful night when the old Café des Westens closed its doors forever and Richard went around collecting our signatures. That sampling of immortality for his autograph book was the last service he was able to perform for literature. Then Richard vanished, and it took a while before he surfaced in the Romanisches Café. Imagine the pain he felt, returning home as a visitor and an outsider, calling for newspapers instead of distributing them?!. .

For a while a rumor did the rounds that Richard was going to open a new Café des Westens. Nothing would have been more natural. His physical condition, his training, his outlook — all qualified him as an ideal host for modern literature. But nothing happened; Richard did not open another establishment. Half a year later he was forgotten. Not only because people still owed him money; he was forgotten for historical reasons, like a writer who has outlived himself. Richard once had a part in a movie that dealt with the literary milieu of the West End of Berlin. Who knows where that film is playing now? Not once but twice Richard’s portrait was hung, painted by renowned artists — one of them was König — in the Sezession. Art treated him as a patron merits. Today the portraits are hanging in some chilly drawing room somewhere, where no one has any idea of Richard’s character. . And a new generation of writers is growing up, without Richard to stand over their cradles. To think that they will never know Red Richard!

One day he showed me a box of butterflies. They were wonderful butterflies and moths, velvety, particolored, red ones and red-and-black and black-and-yellow ones. Someone had invented a process that kept the delicate covering of dead butterflies intact. Richard bought the — as it were — embalmed butterflies to make brooches out of. There are women who will wear insects on their bosoms, I thought. Richard is saved.

A couple of months later, I saw that Richard had a postcard from Leopold Wölfling, the well-known Habsburg archduke. “Dear Richard,” the card began. It was the parallel between their historical circumstances that had brought them together. Richard the Red, ex-king, and Leopold Wölfling, ex-prince, were friends. Leopold Wolfling wanted to open a butterfly exhibition in Vienna. But the ladies didn’t want butterflies. Brooches are worn on exposed and strategic places — and the lacquered butterfly wings were not robust enough to be certain of withstanding an energetic male attack! Now, if Richard had come up with something revealing, say an original form of décolletage, that would have been another matter! But he had offered a barrier instead. The times are not that interested in barriers.

The business did badly, and now Richard is doing badly. But his personal destiny, which in spite of everything seems to put news on his path, chose him of all people to discover Rathenau’s murder. Richard happened to be walking along Königsallee, ten minutes after the assassination. He knew just what to do. Richard called the newspapers. If it hadn’t been for him, the extra editions could have been delayed by — why, an hour or by even more!

That was the last time Richard made contact with history. Every evening he sits at a little café on the Kurfürstendamm and reads the papers — papers that have passed through others’ hands. He is said to own some shares on the stock market. Maybe he is able to live on them. His soul wanders the hunting grounds of the past. Whenever I see him I feel as melancholy as if I had just been looking at an old newspaper, or reading old articles of mine.

That’s how dear Richard is to me. .

Neue Berliner Zeitung—12-Uhr-Blatt, January 9, 1923

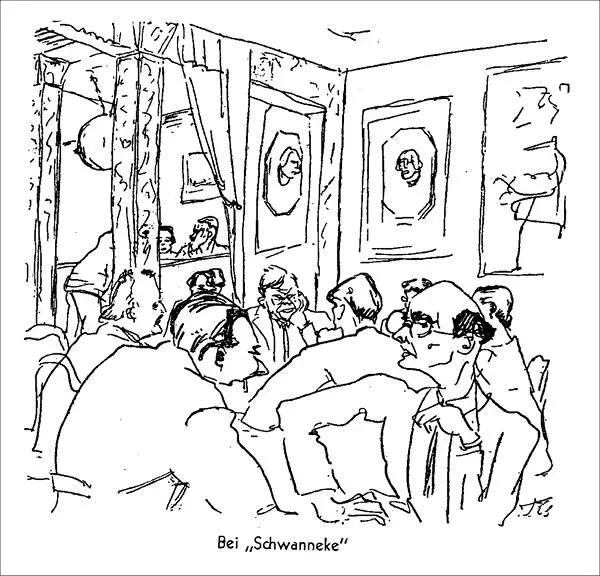

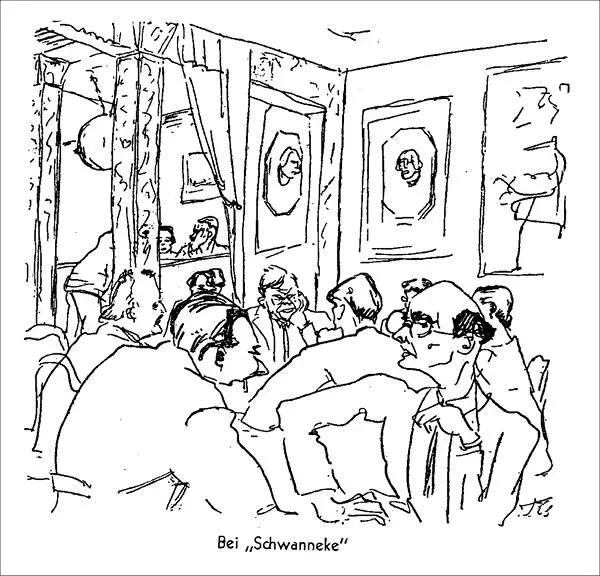

22. The Word at Schwannecke’s (1928)

“At Schwannecke’s”

Although the noise of the chattering clientele is much more significant than the topics of their chatter, it does finally constitute that type of social and indistinct expression that we refer to as rhubarb. The very particular volume in which people tell each other their news seems to generate all by itself that acoustic chiaroscuro, a sounding murk, in which every communication seems to lose its edges, truth projects the shadow of a lie, and a statement seems to resemble its opposite. And, just as it is difficult to see an object clearly by the light of a harsh but flickering flame, so it is difficult for the man straining his ears to evaluate what he has just heard, particularly — as is most often the case — when it is told him in confidence.

The watering hole for Berlin artists and literary figures — where one can be sure to find at midnight all those who only hours before had sworn that they would never go there again, yes, that they hadn’t set foot there for years — houses a class of established bohemian whose creditworthiness is beyond question. None of the clientele really needs to go to bed any later than his bourgeois instincts would tell him to. And each of them, at the end of every evening, promises himself not to go there tomorrow. But the fear that his friends, who are waiting to have a nice talk with him, would say nasty things about him behind his back, prompts him bravely to show his face when it might actually be more courageous to stay away. He comes so as not to disturb the harmony — formed of fear and distrust — of the nooks and corners, and to protect himself and his table mates from the calumnies that are waiting on the lips of those at the next table. If someone had the ability to sit at every table at once, he would hear nothing but good about himself, and yet even such contortions would pale in comparison to those of the others. Still, many approach the very cusp of the miraculous by table-hopping very quickly to keep tabs on what is being said. But even so they fail to match the speed with which those who remain seated change the subject — and, on occasion, their minds as well.

Admittedly there are also some seated customers of such seniority that their rank just about permits them to stand when required, but no longer to visit other tables. Even they are not proof against the fear that somebody somewhere might be saying bad things about them. But they bear the burden of being unpopular as proof of their importance — and these eminences turn the suspicion that less elevated customers are careful to disguise as courtesy into naked contempt and disdain. All the people one doesn’t need right now are — for the person who will need them in a year’s time — no more than air* which he breathes but doesn’t need to see. Softly, softly! Before long they will have roused themselves from their transparent anonymity into that pseudonymous corporality without which it would be impossible to occupy a seat behind an office desk. Those who even today ask for nothing better than to be shadows of bodies will one day cast shadows of their own, shadows of patronage over new, anonymous, transparent airy shades. It will fall to them to dole out the movie-reviewing assignments, which today fall into their laps once or twice a year like manna from heaven. They themselves will be participants at conferences they are today sent out to cover, and they will attend premieres sitting next to critics, critics themselves, but representatives of some “new direction,” with a new terminology, which will help save them from making judgments and ensure that they stick to prejudices. Therefore it is advisable for cautious spirits not to overlook anyone here, to take in even the least of those present with a certain respect, and to greet the shades in such a way as to suggest that they had the power of speech and were capable of replying. In the long years I have observed the German literary business, I have seen zeroes attach themselves to real numbers, and amount to totals that need to be reckoned with. Yes, a few of the company at Schwannecke’s who seemed merely to serve the negligible function of being ornamental vertical lines have become strokes that put paid to the innocent plans of others.* And some illiterates whom one might come upon in the anterooms of editors, trying to spell their way through newspaper headlines, are now all at once reviewing books themselves.

Читать дальше