Redesigning facades on the Kurfürstendamm, 1927.

Still more confusing is interior design. I have learned that those hygienic white operating theaters are actually patisseries. But I continue to mistake those long glass tubes mounted on walls for thermometers. Of course, they are lamps, or as people more correctly say, “sources of illumination.” A glass tabletop isn’t really there to permit the diner to view his own boots in comfort during a meal, but to help a metal ashtray produce those marrow-piercing, grating sounds when slid across it. There is a class of objects that are wide, white, hard-wearing, deep, and hollow; have no feet; and look like chests. On these, it seems, people sit. Of course they aren’t anything as straightforward as chairs, but rather “seating accommodation.” Similar confusions are also possible with those living objects collectively referred to as “staff.” A girl in red pants and blue jacket with gold buttons, with a round fez on her head, whom — but for the fact that the treachery of these times has begun to dawn on me — I would certainly have taken for a man, but then was foolish enough to take for a sort of royal guard in a costume drama. In fact this girl is in charge of the cloakroom, and of the sales of cigarettes and of those long, slender unjointed silk dolls, who look like merry hanged corpses.

Domestic interior design is a fraught affair. It makes me hanker for the mild and soothing and tasteless red velvet interiors in which people lived so undiscriminatingly no more than twenty years ago. It was unhygienic, dark, cool, probably stuffed full of dangerous bacteria, and pleasant. The accumulation of small, useless, fragile, cheap, but tenderly bred knickknacks on sideboards and mantelpieces produced an agreeable contempt that made one feel at home right away. Countering all the tormenting demands of health, windows were kept closed, no noise came up from the street to interrupt the useless and sentimental family conversations. Soft carpets, harboring innumerable dangerous diseases, made life seem livable and even sickness bearable, and in the evenings the vulgar chandeliers spread a gentle, cheerful light that was like a form of happiness.

The lives of our fathers’ generation were lived in such poor taste. But their children and grandchildren live in strenuously bracing conditions. Not even nature itself affords as much light and air as some of the new dwellings. For a bedroom there is a glass-walled studio. They dine in gyms. Rooms you would have sworn were tennis courts serve them as libraries and music rooms. Water whooshes in thousands of pipes. They do Swedish exercises in vast aquariums. They relax after meals on white operating tables. And in the evening concealed fluorescent tubes light the room so evenly that it is no longer illuminated, it is a pool of luminosity.

Münchner Illustrierte Presse, October 27, 1929

18. The Very Large Department Store (1929)

Large department stores are nothing new in Berlin. But there seemed to be the odd person who bemoaned the lack of a very large department store. Some were not content with the existing four- or five- or six-story department stores, and they dreamed ambitiously of department stores that were to have ten or twelve, or even fifteen stories. It was not part of their plan to be nearer to God — which would have been a futile endeavor in any case — because, on the basis of everything we know, we don’t get any nearer to him by climbing up toward the clouds, but if anything perhaps the opposite: the nearer we are to the dust of which we are made. No! The people who dreamed of very large department stores were only out to lift themselves above the smaller department stores, just as with today’s runners, one of whom tries to outstrip the other not to reach his target the sooner, but merely to reach some arbitrary mark before the other does. The dreamers of department stores dreamed of a skyscraper. And so one day they built the very large department store, and everyone went along to look at it, and I went with them. .

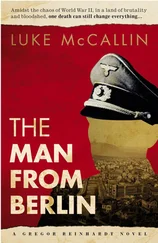

The Karstadt department store on Hermannplatz with swastika flags flying (1939).

The old, the merely large, department stores are small by comparison, almost like corner shops, even though in its essence there is little to distinguish the very large department store from the merely big ones. It is simply that it has in it more merchandise, more elevators, more shoppers, flights of stairs, escalators, cash registers, salesmen and floorwalkers, uniforms, displays, and cardboard boxes and chests. Of course the merchandise appears to be cheaper. Because where there are so many things close together, they can hardly help not thinking of themselves as precious. In their own eyes they shrink, and they lower their prices, and they become humble, for humility in goods expresses itself as cheapness. And since there are also so many shoppers crowded together, the goods make less of a challenge or an appeal to them; and so they too become humble. If the very large department store looked to begin with like a work of hubris, it comes to seem merely an enormous container for human smallness and modesty: an enormous confession of earthly cheapness.

The escalator seems to me to typify this: It leads us up, by climbing on our behalf. Yes, it doesn’t even climb, it flies. Each step carries its shopper aloft, as though afraid he might change his mind. It takes us up to merchandise we might not have bothered to climb an ordinary flight of steps for. Ultimately it makes little difference whether the merchandise is carried down to the waiting shopper, or the shopper is borne up to the waiting merchandise.

The very large department store also has conventional stairs. But they are “newly waxed” and anyone going up them runs the risk of slipping and falling. I think they would like to have dispensed with them altogether, those old-fangled things, that in the context of elevators and escalators seem little better than ladders. To make them appear yet more dangerous, they are newly waxed. Almost unused, they do nothing but carry their own sheer steps aloft. Leftovers from the old days of ruined castles and merely large department stores — before the advent of the very large kind we have now.

The very large department store would perhaps have been built much higher still if it weren’t that people believed it required a roof terrace where the shoppers could eat, drink, look at the view, and listen to music — and all without getting too cold. This seems a rather arbitrary belief, as it doesn’t seem to be ingrained in human nature that, following the successful purchase of bed linen, kitchenware, and sports equipment, the shopper should feel the need to drink coffee, eat cake, and listen to music. But what do I know? Perhaps these requirements are built into the human character at some deep level. Anyway, it is to cater to them that the roof garden was built. In the daytime a lot of people do sit there, eating and drinking, and though it is not for me to assume that they do so without pleasure, it still looks to me as if they were merely sitting and drinking to justify the existence of the roof terrace. Yes, even such pleasure as they do evince may have nothing more than justificatory motives. If the people themselves, having been borne aloft by the escalators, were still, even in their diminished mobility, recognizable as shoppers, then, by the time they got to the roof, they had reached such a degree of passivity that utterly equated them to merchandise. And even though they pay, still it seems as though they were paid for. .

Читать дальше