In complete torpor they are regaled with the sounds of an excellent orchestra. Their eyes take in distant steeples, gasholders, and horizons. Rare delicacies are offered in such profusion and with such insistence that their rarity is lost. And just as, within, the merchandise and the shoppers became modest, so too the delicacies on the roof become modest. Everything is within reach of anyone. Everyone may aspire to anything.

Therefore the very large department store should not be viewed as a sinful undertaking, as, for example, the Tower of Babel. It is, rather, proof of the inability of the human race of today to be extravagant. It even builds skyscrapers: and the consequence this time isn’t a great flood, but just a shop. .

Münchner Neueste Nachrichten, September 8, 1929

19. “Stone Berlin” (1930)

Berlin is a young and unhappy city-in-waiting. There is something fragmentary about its history. Its frequently interrupted, still more frequently diverted or averted development has been checked and advanced, and by unconscious mistakes as well as by bad intentions; the many obstacles in its path have, it would seem, helped it to grow. The wickedness, sheer cluelessness, and avarice of its rulers, builders, and protectors draw up the plans, muddle them up again, and confusedly put them into practice. The results — for this city has too many speedily changing aspects for it to be accurate to speak of a single result — are a distressing agglomeration of squares, streets, blocks of tenements, churches, and palaces. A tidy mess, an arbitrariness exactly to plan, a purposeful-seeming aimlessness. Never was so much order thrown at disorder, so much lavishness at parsimony, so much method at madness. If fate can have arbitrariness, then this city has become the nation’s capital through a whim of German fate. As if we wanted to prove to the world how much harder it is for us than it is for anyone else! As if there had been one contradictory detail — a capstone — lacking from the structure of our contradictory history! As if we had felt challenged to come up with an aimlessly sprawling stone emblem for the sorry aimlessness of our national existence! As if we had required one more proof that we are the most long-suffering of the peoples of the earth — or, to put it more malignly and medically: the most masochistic. The story of how absolutism and corruption, tyranny and speculation, the knout and shabby real estate dealings, cruelty and greed, the pretense of tough law-abidingness and blathering wheeler-dealing stood shoulder to shoulder, digging foundations and building streets, and of how ignorance, poor taste, disaster, bad intentions, and the occasional very rare happy accident have come together in building the capital of the German Reich is most fascinatingly told in Werner Hegemann’s book: Stone Berlin.

Here in Germany expert understanding tends to go hand in hand with barely comprehensible jargonizing. Expertise lacks style, knowledge stammers just as if it were ignorance, and objectivity has no opinions. Werner Hegemann is one of the rare exceptions (no less German for all that) in whom expert knowledge makes for passion, and passion feeds hunger for knowledge. Style sharpens his judgment, the facts plead for his opinion — if it needed a plea — truths underpin his convictions, and a winning edge of malice sharpens, points, and rounds the writing. This edge of malice produces something close to a vendetta when the subject turns to Frederick the Great, whose sobriquet the author has evidently vowed never to use without encasing it in quotation marks. He is Werner Hegemann’s special enemy. Not since Voltaire, it seems to me, has Frederick the Great had to suffer a wittier antagonist. Here is the embodiment of the vengeance of German literature on the Frenchified Prussian. The present writer lacks the historical knowledge to refute or uphold the author’s views. He is a “layman,” but the “reader” in him would affirm that the passages of the book he most enjoyed were where Hegemann’s stylistic adroitness fed on the weakness of his historical enemy, and where the sharpness of the writing is surely sufficient to make even Frederick’s fans admire Hegemann’s authorship.

It is, so far as I know, the first successful attempt to follow the stone traces of history in such a way that makes it possible to hear the soft and vanishing tread of the past. Reading it is like looking at someone’s testament and hearing it read in the testator’s voice. Anecdotes, seemingly merely tossed in, acquire symbolic weight through the way in which they are used and the context in which they appear. The author’s near-omniscience in the fields of literature, history, philosophy, and architecture is fused together by his overall historical perspective and his style, so that his “expertise” becomes unobtrusive, and no more than a natural element of his language. The private in the historical is raised to the level of the human, thanks to his fine passion for justice. Passion for justice: That seems to me particularly to characterize this book and its author. With the zeal of the true writer he pursues injustice throughout history, like God following sin through generations still unborn. The striking relevance of the book to today is also rooted in this quality. It is fortunate enough to appear at a time when the scars of the absolutist lash are healing over rapidly, but confusion shows no signs of lessening. The stupidity that is our inheritance and the ignorant snobbery that we have learned from our recent rulers dim and becloud our freedom. Now we have this capital city. Its interests are the same as ours. From its past, for which we are only partly responsible, we ought to learn how to shape its future, for which the whole of Germany is now taking responsibility. Stone Berlin (designed and illustrated, by the way, with great beauty and attention to detail) appears just as further damaging scandals are shaking the city and the nation, which seems as yet unaware that Berlin is its chosen representative. From the fact that it has found a historian of this stamp, we ought to acquire confidence that it has a future more wholesome and less warped than its past has been. A city that has had so much knowledge and passion devoted to it surely has a historical mission. It may indeed be young and unhappy, but we may hope it is a city for the future.

Das Tagebuch, July 5, 1930

Part VI. Bourgeoisie and Bohemians

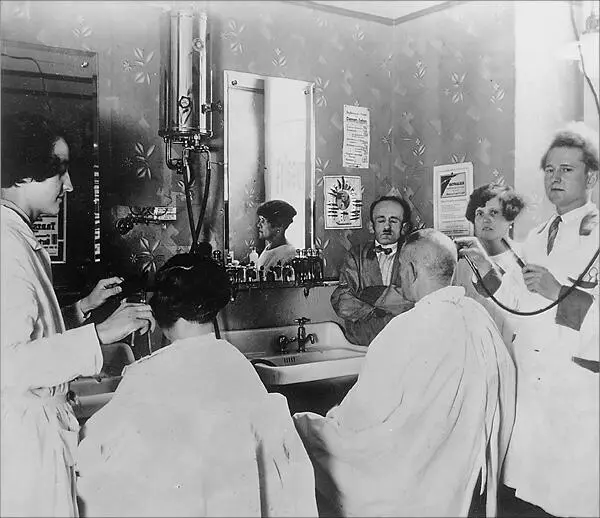

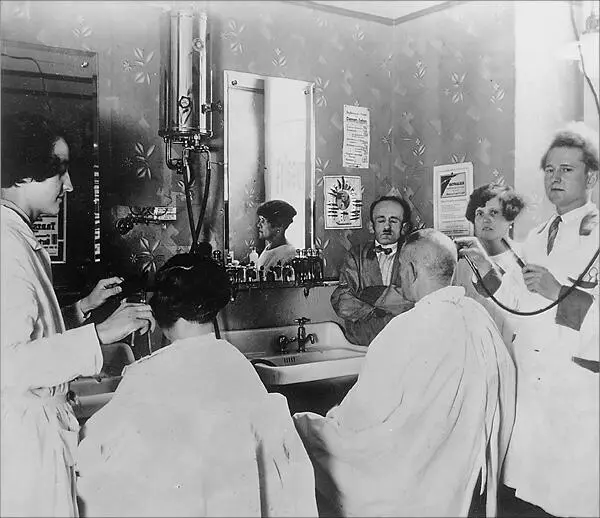

20. The Man in the Barbershop (1921)

On Sunday morning there was a stifled, almost canned heat in the barbershop: a desiccated temperature.

Sunlight, split into golden bars by the blinds, bullioned its way into the room. Scissors clacked avidly, and a large fly was buzzing about.

(To date no poet has hymned summer in a barbershop in his iambs. That would be a task worthy of a Theodor Storm, or an Eduard Mörike.* Think of the mild scrape of whetting blade on tautened strop; the soft plashing of soapy water; the flushed cheeks of the apprentices, who — because the master and journeyman are too tired today — don’t get their usual smacks: a holiday from discipline!)

But people like to talk at the barber’s, even on hot days. And on that particular Sunday morning they were certainly talking a lot.

Читать дальше