But unfortunately it seems more likely that it wasn’t. .

Münchner Neueste Nachrichten, September 29, 1929

Part VII. Berlin’s Pleasure Industry

24. The Philosophy of the Panopticum* (1923)

Currently, in Lindenpassage, there is a historic auction of the last of the Berlin panopticums. A whole world of wax, curiosity, expert copies of life, plastic horror, is being broken up. It was a police report in wax, a three-dimensional chronique scandaleuse —and at the same time it immortalized those high points of world history that seemed made for the panoptical form: parades, coronations, five-star pageants. Thanks to a cannily symbolic layout, the Chamber of Horrors was just one step away from the Fairy-tale Hall, and the Rulers of Europe a curtain’s thickness from the Fun House. It was the revelation of the paradoxical philosophy of the panopticum that earthly grandeur and horror became ridiculous by being given permanence in wax. Never has a memorial industry so stripped its objects of all dignity as the panoptical one. It made monuments without the pathos of piety. A wax Goethe quite naturally lacks the gravitas of a marble one. The cheap material was able to achieve a lifelike color but not the afflatus of genius. The only achievement of the panopticum was the unintentional ridiculousness with which it atoned for the pathos of this world, and turned it into a kind of Fun House Gallery.

This is because the chief characteristic of the panopticum, its frightening verisimilitude, is finally ridiculous. It is the — actually profoundly unartistic — impulse to produce exterior likeness rather than inner truth: the same impulse as naturalistic photography and the “copy.” A wax mass murderer is comical. But a wax Rothschild is also ridiculous. The medium has robbed the one of his gruesomeness and the other of his dignity.

The panopticum has fallen victim to the times, to our awakened pleasure in movement, which expresses itself in the popularity of film. In the age of the movies, the panopticum has no part to play. In an age of intense bustle, rigidity is impossible, even if it attempts to mask its deadness in pedantic lifelikeness. A moving shadow means more to us than a body at rest. We are no longer taken in by a fixed grin. We know that only death has a rictus.

For the very last time the models have a kind of urgency and newsworthiness. The auction is being held — oh, the irony! — in the rooms of the White Mouse. The wax heads are piled up in the anteroom. For practical reasons they have been detached from their bodies, but not completely from the vestiges of their former lives. Here a bearded head has managed to hang on to its cravat, there a shirtfront remains draped around a severed neck. A naked wax girl still smiles, even after her body shattered into pathetic pieces as it was being moved, and the contrast between the smiling lips and the broken body is so gruesomely ironic that for the very first time, a suggestion of grotesque animation emanates from the figure. It looks as though a mass grave of preserved heads had been discovered, a grisly charnel house of dead life. All these beings lost their heads in the flower of their youth, it looks as though their souls had been vouchsafed some joyful experience, and the painful end that overtook them seconds later had no time to change their expressions. Beside the two hundred heads living men bargain and haggle, and enormous moving men drink soup with slurps of satisfaction.

In the room next door are stuffed apes and skeletons of apes, the dusty booty of popular science that shows only the results and says nothing about connections and details. Minerals and rare plants and anthropological bric-a-brac, Indian quivers and spears and arrows: everything an example of semicivilization and indiscriminate dabbling, the world of insatiably curious encyclopedia subscribers, always eager, always wrong. The items provoke a kind of sentimental contemplation, and they too, like the wax figures, are victims of these times, which create one-sided specialists in the hope of making people of deep learning, as opposed to people of broad and general culture.

In the auction room they sell elephant tusks; two men almost come to blows over a piece of wood carving and a copper vat of supernatural dimensions, a container from the time of icthyosaurs. It is astonishing that a man can spend a hundred million and more on a single day on a lot of tin, wood, bronze, broken tables, thrones, and glass cabinets. Watching him, I suddenly understand the point of this auction: The man is not buying out of sentiment. He is, rather, an exemplar of the new times, in a short fur coat, cigar jammed between metal teeth, all calm and calculating: a schemer, a man working his percentages, confident of victory. God knows what his hands will make of those pots and plates and carvings, how the horrid monsters will change in his storehouses. Twentieth-century man can turn ducats out of all sorts of trash.

Which is really the higher purpose of the panopticum.

The gold maker of our time, the modern alchemist, makes capital out of the sensation of the past. He finds the stone of wisdom — not by experimenting but by speculation — in every medieval cooking pot. Whatever he touches appreciates.

So there he stands, victor over the ephemeral world, gold maker, highest bidder, all-purchaser. His spacious girth has room for an entire panopticum, pots and pans, spears and apes, murderers and princes, the grotesque and the trivial. He swallows it all up — the ultimate redeemer of panoptical existence.

Berliner Börsen Courier, February 25, 1923

25. An Hour at the Amusement Park (1924)

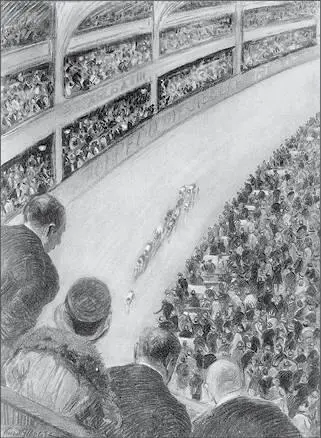

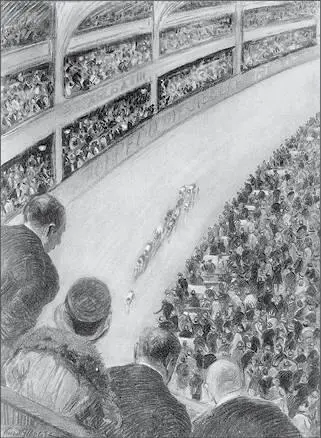

Spring in Berlin received its official sanction as a season of merriment ( Amüsemang ),* with the opening of the enormous Luna Park, just beyond the Halensee Bridge, set by the God of sensations at the very end of the Kurfürstendamm, which seems like one never-ending promise of sensations. Here the fun becomes insane, the absurdity hyperbolic, the jollification both strenuous and harmless. There are infernal machines that cause bitter sweat before they rouse any joys: a deranged pyramid that tries to top its own summit. Undemanding fun becomes its own caricature. How strange that someone trying to have a good time will walk up an uncertain jazz band staircase, get stuck halfway up, unable to go up or down, and instead of laughing, finds himself laughed at by everyone else!

The whole purpose of this grotesque machine is to expose the person who entrusted himself to its mercy in his full inadequacy. The point of the other amusements is the same. Woe betide him who breaches the circumference of the “Devil’s Wheel”! The good fellow will walk out onto a round arena, and look back over his shoulder with a smile. Suddenly the signal will sound, what was solid becomes flimsy, what was secure uneasy, the floor spins, bodies collide with one another, outstretched arms vainly seek for somewhere to grip in this suddenly deranged world of violent spinning. You may reach for the barriers, but they too are spinning, the coattails of the man next to you are flying out, the cane propped on the quaking ground is shaken free of one’s trembling grasp, a savage draft seizes you by the neck and hurls you centuries back. You will land somewhere in the Stone Age! Never yet has such furious movement brought in its train such slowness in the passage of time. Everything is spinning, only time stands still. The rotation goes on forever. And when the wheel finally stops spinning, the riders in their relief forget that they have paid money to enjoy themselves, and only had the fright of their lives. They feel glad to have gotten out alive.

Читать дальше