In the corner the band is installed, not to sit but to perform incessant and foolish movements that remind one of the exercise “marching in place.” Merely switched to the world of bacchic militarism from that of war, the saxophone — profane trump of a profane, so to speak, penultimate judgment — flashes and gleams, moans and wails, yelps and croons. The musicians do not wear jackets. They sit in their shirtsleeves like bowlers, in sports shirts like tennis players, in that relaxed Anglo-Saxon uniform that seems to suggest that the production of sound and noise is more a sporting vocation than an artistic one. Bar girls all over the world are made out of the same substance of beauty, with little concession to the local variations of climate, geology, and race, poured equally over every country by a prodigally lavish godhead, to produce that international, slender, narrow-hipped type of child-woman in whom vice is paired with training, knee-jerk modernity with traditional seduction-by-helplessness, active and passive suffrage with the willingness to be bought. In every city there is the prototypical young, or rather, ageless, player in male dress (this the only overt indication of its sex): smooth features and slicked-back hair, padded shoulders and compressed hips, baggy, billowing pants and pointed patent leather boots — and the casual demeanor out of fashion magazines, the nonchalance of a window dummy, the fake worldweariness in the glassy stare, and the thin lips touched up by nature itself in homage, of course, to certain photographic originals. Couples get up simultaneously and indifferently to do their athletic dance routines. The movements of the musicians are livelier than those of the dancers. It’s as though the marionette-like movements of the musicians had taken all the life out of the dancers. The couples who, under the heading “classic modern dance,” go from city to city earning their daily/nightly bread with the same mechanical smile that consists only of the baring of brilliantly maintained teeth — they at least produce an imitation of life. There is no owner to be seen anywhere, as if these bars didn’t actually belong to anyone, as if they were institutions of public luxury, just as buses and streetlights are institutions of utility, as though the entertainment industry wanted to prove its close relationship to the utility industry.

In a city like Berlin there are stock companies that are capable of satisfying the entertainment needs of several social classes at once, catering to the “cosmopolite” in the West End, providing “solid bourgeois” pleasures in other parts of the city, and in a third supplying that part of the lower middle class that wants to have some inkling of the “grand monde” with its very own “third-class establishments.” And just as in a department store there are clothes and food for every social class and even for the myriad delicate nuances in between, carefully graded by price and “quality,” so the great names of the pleasure industry supply every class with the appropriate entertainment and the appropriate — and affordable — drink, from champagne and cocktails to cognac to kirsch to sweet liqueurs down to Patzenhofer beer. In the course of a single night, in which my mournfulness was such that it compelled me to experience the pain of every class of big-city dweller athirst for joy, I slowly made the rounds from the bars of the West End of Berlin to those of the Friedrichstrasse, and from there to the bars in the north of the city, finishing up in the drinking places that are frequented by the so-called lumpenproletariat. As I went, I noticed the schnapps getting stronger, the beers lighter and brighter, the wines more acidic, the music cheaper, and the women older and stouter. Yes, I had the sensation that somewhere there was some merciless force or organization — a commercial undertaking, of course — that implacably forced the whole population to nocturnal pleasures, as it were belaboring it with joys, while husbanding the raw material with extreme care, down to the very last scrap. Saxophonists who have lost their wind playing in the classy bars of the West End carry on playing to the middle class till they lose their hearing, and then they wind up in proletarian dives. In accordance with a strict plan, dancers start out reed thin, to slip slowly, in the fullness of time and their bodies, down from the zones of prodigality to those where people keep count, to the third where people save their pennies, to the very lowest finally, where the expenditure of money is either an accident or a calamity.

One of these places — it was already far along in years, a hoary ancient among the clubs of Berlin — was celebrating its fiftieth anniversary, and was giving out detailed anniversary programs, complete with unobtainable photographs of long-gone vaudeville stars and popular favorites and a “historical look back.” From this it appeared that the establishment, having once been founded and run by a single man, has fallen into the numerous hands of a consortium, a consortium, I like to imagine, of deadly serious fellows, heavyweight fat cats. There is the photograph of the founding father: the broad round face of a man who knew to live and let live, with the twinkling eyes of a connoisseur, with a mighty upturned moustache betraying a kind of martial good humor, and a slow smile that legitimates the man’s unquestioned desire for profit.

There follow pictures of the “famous numbers,” the “diseuses,” a race of courageous women setting foot on the stage as on a battlefield, armored in corsets, in long skirts, under which peep out — flirtatiously, seductively, sinfully — snow white or salmon pink stockings and tightly laced dancing shoes, Boadiceas with bare throats and powerful shoulders and with abundant piled-up hair on their heads, such that a little nodding double-entendre can’t have been an easy matter; and finally the dancers with round, shapely legs, sewn, one would think, into the whirling expanse of ruffled and lacy underskirts, loose girls of sweet harmlessness and easy virtue. Yes, that’s the way it was then. The clubowner walked around among the tables, and nodded and smiled and allowed his patrons to live and encouraged them to sin as hard as they could. The jokes were terrible, but the people were cheerful, the women were very dressed, but at least they were flesh and blood, and not the product of hygienic training. Pleasure was always a business, but at least it wasn’t yet an industry.

Münchner Neueste Nachrichten, May 1, 1930

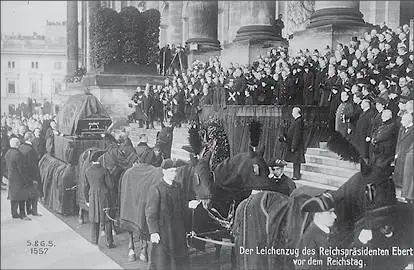

Part VIII. An Apolitical Observer Goes to the Reichstag

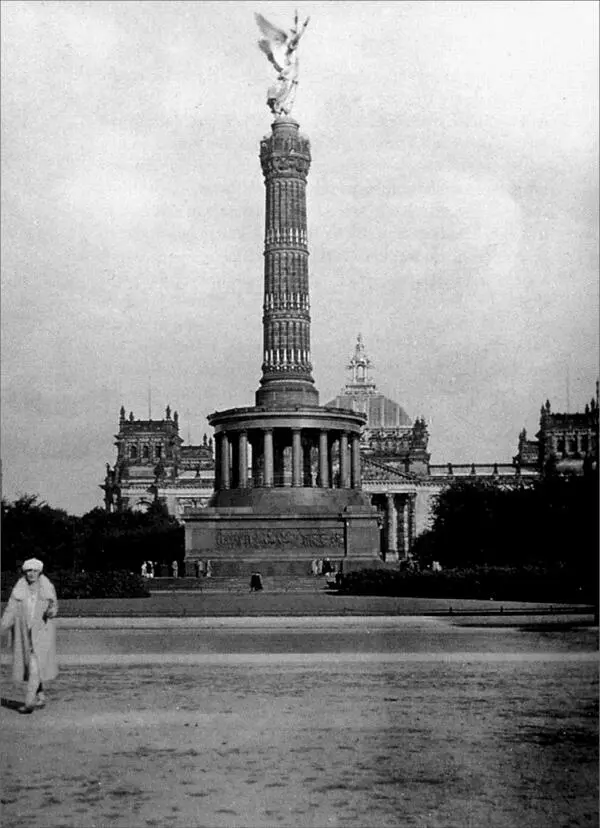

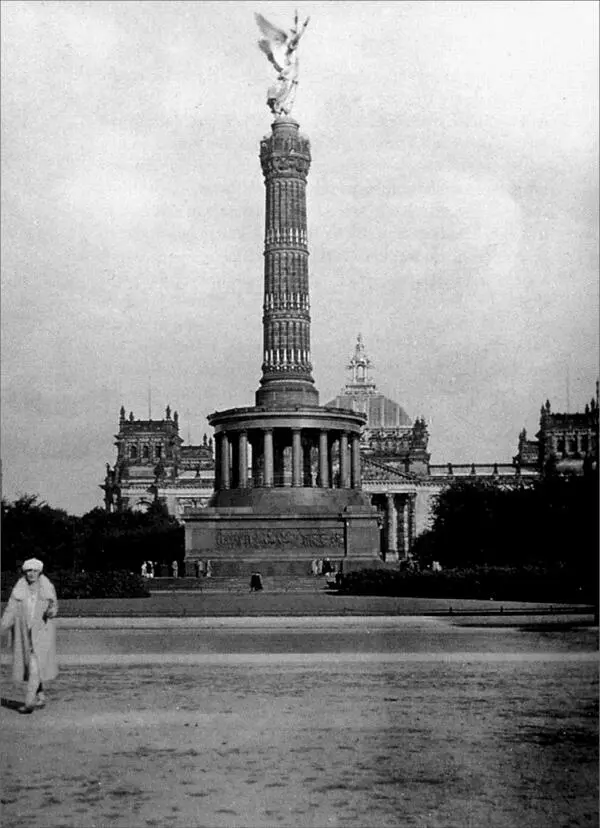

29. The Tour Around the Victory Column (1921)

The sky has got itself all blued up, as though it were going to get its picture taken, and the March sun is friendly and eager to please. The Victory Column* soars up into the azure, naked and slender, as though sunbathing. Following the law that governs the popularity of all outstanding personalities, it has now, following its accident, attained the level of popularity that only failed assassinations may confer.

For many years it was neglected and lonely. Street photographers with long-legged flamingoesque equipment liked to use it as a free backdrop for the vacant smiles of their human subjects. It was a little knickknack of German history, something that appeared on picture postcards for tourists, a suitable destination for school outings. No grown-ups or locals would dream of going up it.

Читать дальше