And then a network of wires overhead, a slashed and cross-hatched sky, as though some engineer had scrawled his deranged circuits across the ether. If you pressed your ear against a pole, you could hear strange noises within, ghostly voices, as if whole African tribes were howling in blood lust or worship, and you could hear them here in Berlin.

Georg B. bought himself a subway ticket and stood in bewilderment on the platform, allowed himself to be pushed onto a train, and then he thought the underworld had gone crazy too. Could the dead still sleep undisturbed? Were their bones not being rattled in their graves? Did the roar of a train not infect their silence? And what kept the upper world from collapse? How could the road fail to shatter every time a train passed below, throwing thousands of people, cars, horses, wires, and everything else to perdition?

Georg B., the seventy-year-old, wanders around like a youngster. He wants to work. Energy bottled up inside him for half a century seeks to express itself. Who would believe him? In his bewilderment he’s not allowed to stop and draw breath. Is he dying? Is he facing his own end? The experience of this century mocks human laws. Experience was stronger than death. The conquest of the city is followed by the conquest of work. Man, surrounded by machines, is compelled to become a machine himself. His galvanized seventy years are fidgeting, banging, shaking. B. must work.

Neue Berliner Zeitung—12-Uhr-Blatt, February 24, 1923

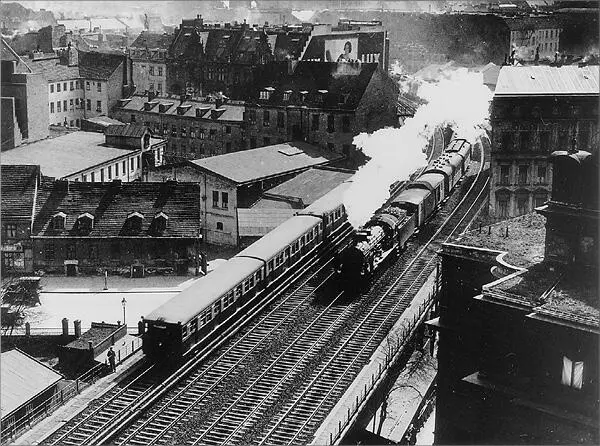

12. The Ride Past the Houses (1922)

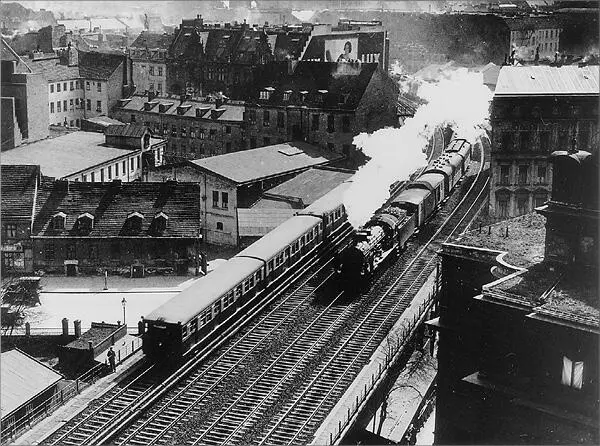

The S-Bahn line goes right past the houses, affording its passengers many curious and interesting sights — especially in springtime, when walls are prone to indiscretion, when casements reveal the idylls behind, and courtyards betray their secrets.

Sometimes a ride on the S-Bahn is more instructive than a voyage to distant lands. Experienced travelers will confirm that it is sufficient to see a single lilac shrub in a dusty city courtyard to understand the deep sadness of all the hidden lilac trees anywhere in the world.

Which is why I return from a ride on the S-Bahn full of many sad and beautiful impressions, and when I navigate a little bit of the city, I feel as proud as if I had circumnavigated the globe. If I imagine the courtyards a little more gloomy, their lilac trees a little scrawnier, and the walls a couple of yards higher and the children a shade or two paler — then it’s as though I’d been to New York, having sampled the bitterness of the metropolis, because most major discoveries can be made very locally, either at home or a few streets away. Phenomena and atmospheres and experiences differ not in their essence, but in secondary qualities like scale.

Electric S-Bahn train and steam train together.

A wall has a physiognomy and a character of its own, even if it doesn’t contain a window or anything else that reinforces its connection to life, beyond a billboard for, say, a brand of chocolate, placed so that its sudden flash on our retina (yellow and blue) will make an indelible impression on our memory.

Behind the wall, meanwhile, people will be getting on with their lives, little girls will be doing their homework, a grandmother will be knitting, a dog gnawing its bone. The pulse of life will beat through the cracks and pores of the silent wall, break through the tin simulacrum of the Sarotti chocolate, beat against the windows of the train, so that their clatter acquires a vital, human sound and makes us hearken at the proximity of a related life so close at hand.

It’s a curious thing, how much the people who live in houses bordering the S-Bahn resemble one another. It’s as though there were a single extended family of them, living along the S-Bahn lines and overlooking the viaducts.

I have come to know one or two apartments near certain stations really quite well. It’s as if I’d often been to visit there, and I have a feeling I know how the people who live there talk and move. They all have a certain amount of noise in their souls from the constant din of passing trains, and they’re quite incurious, because they’ve gotten used to the fact that every minute countless other lives will glide by them, leaving no trace.

There is always an invisible, impenetrable strangeness between them and the world alongside. They are no longer even aware of the fact that their days and their doings, their nights and their dreams, are all filled with noise. The sounds seem to have come to rest on the bottom of their consciousness, and without them no impression, no experience the people might have, feels complete.

There is one particular balcony with iron bars, like a cage hung in front of the house, and in one particular place on it, all through the spring and summer, hangs a red cushion, rain or shine, like an implacable fleck of oil paint. There is a courtyard that is quite crisscrossed with clotheslines, as if some monstrous antediluvian spider had spun its stout web there from wall to wall. A dark blue pinafore with big white dobs of eyes always billows in the breeze there.

Over the course of my rides, I’ve also come to know a little blond girl. She sits by an open window, pouring sand from little toy dishes into a red clay flowerpot. She must have filled five hundred of those flowerpots by now. I know an old gentleman who spends all his time reading. The old man must have read his way through all the libraries of the world by now. A boy listens to a big phonograph on the table before him, its great funnel shimmering. I catch a brassy scrap of tune and take it with me on my journey. Torn away from the body of the melody, it plays on in my ear, a meaningless fragment of a fragment, absurdly, peremptorily identified in my memory with the sight of the boy listening.

There are only a few who have nothing to do, and just sit at their windows and watch the trains go by. That tells you how boring life would be without work. Therefore every one of us has a purpose, and even animals have their use. There is no lilac tree in a backyard that doesn’t support drying laundry. That’s the sadness of those backyards: How rare it is for a tree to do nothing but bloom, to have no function but to wait for rain and sunshine, to receive them both and enjoy them, and put forth blue and white blossoms.

Berliner Börsen-Courier, April 23, 1922

13. Passengers with Heavy Loads(1923)

Passengers with heavy loads take their place in the very last cars of our endless trains, alongside “Passengers with Dogs” and “War Invalids.” The last car is the one that rattles around the most; its doors close badly, and its windows are not sealed, and are sometimes broken and stuffed with brown paper.

It’s not chance but destiny that makes a person into a passenger with heavy baggage. War invalids were made by exploding shells, whose destructive effect was not calculation but such infinite randomness that it was bound to be destructive. To take a dog with us or not is an expression of personal freedom. But being a passenger with heavy baggage is a full-time occupation. Even without a load, he would still be a passenger with heavy baggage. He belongs to a particular type of human being — and the sign on the car window is less a piece of railway terminology than a philosophical definition.

Baggage cars are filled with a kind of dense atmosphere you could cut maybe with a saw, a freak of nature, a kind of gas in a state of aggregation. The smell is of cold pipe tobacco, damp wood, the cadavers of leaves, and the humus of autumn forests. What causes the smell are the bundles of wood belonging to the occupants, who have come straight from the forests, having escaped the shotguns of enthusiastic huntsmen, with the damp chill of the earth in their bones and on their boot soles. They are encrusted with green moss, as if they were pieces of old masonry. Their hands are cracked, their old fingers gouty and deformed, resembling peculiar gnarled roots. A few leaves have caught in the thin hair of an old woman — a funeral wreath of the cheapest kind. Swallows could make nests for themselves in the tangled beards of the old men. .

Читать дальше