The Lieutenant Colonel

I sat with him, in his little wooden cubicle. Lieutenant Colonel Bersin is a czarist Russian officer, and a refugee. He has been in Berlin since April. He is old and stiff and proud. His gait is a little crooked, but after all the world has become so crooked. Revolution! And the Little Father is no more. Where is the czar? Where are his epaulettes? Where is the General Staff? He is a veteran of the Chinese war, the Japanese war, the Great war. He was lieutenant colonel on the General Staff. Most recently in Riga. He speaks excellent German but is still pleased that he can speak to me in Russian. He has newspapers and books piled up next to his bed. He reads everything he can lay his hands on. His officer’s cap is on the wall. He shows it to me with a great deal of pride, touching pride, like a child showing off his drum. He would like to work. He wishes he didn’t have to be a burden on the city. He is a lieutenant colonel. How much longer can the Bolsheviks last? Only a little bit, surely! It’s insane! A revolution! Ripping the epaulettes off officers’ uniforms! Where is the czar? The Little Father? Where is Russia? He has a family. His children — perhaps they are married by now; or fled, or even dead! What sort of world is this? A crooked world! Poor, poor lieutenant colonel! History has performed a somersault, and a lieutenant colonel winds up in the shelter for homeless people.

Thousands of people used to pass through the homeless shelter. Now there are a thousand every night. In the morning two or three of the dormitories are combed by the police. They find the people they have been looking for, sometimes.

Others they don’t bother with at all. They know who they are. They have been coming to the shelter for ten years now, or more. Residents. Resident homeless. The provisional or the contingent has become their normal way of life, and they are at home — in their homelessness.

Neue Berliner Zeitung—12-Uhr-Blatt, September 23, 1920

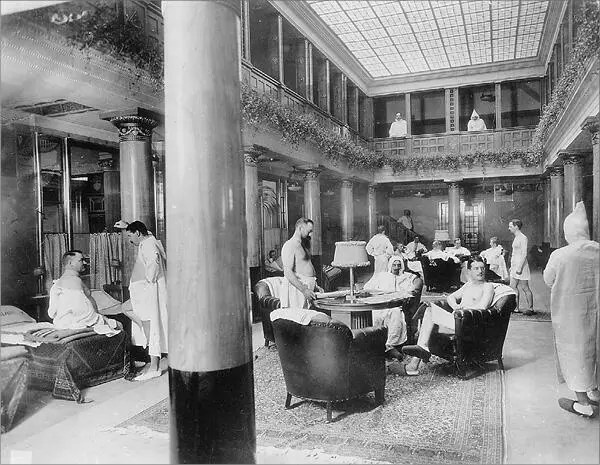

8. The Steam Baths at Night (1920)

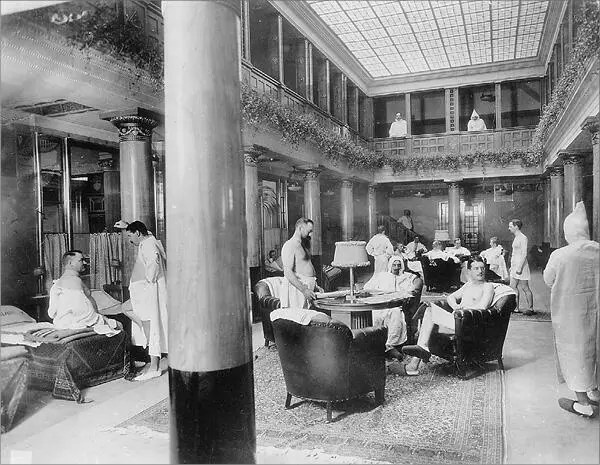

The steam baths in the Admiral’s Palace are once more open all night. During the war their nighttime hours were first curtailed, then stopped altogether. Now you can once more take a steam bath at night.

Before the war a visit here represented the inevitable and indispensable conclusion to a night on the town, and the rejuvenation or rehumanizing of the night owl. Yesterday is swilled off him into the basins, and he emerges from the waters of the Admiral’s Palace clean shaven, reconsecrated, ready for fresh deeds, into the morning air of Friedrichstrasse. The steam baths consituted the break — the “clean break”—between the bacchanals of the night and the day’s gainful employment. It interposed itself between the bar and the desk. Without its ministrations — cast your minds back — it would have been impossible to sustain a rowdy nightlife with anything like the same stamina.

Nowadays, with the domestication of pleasure, with the fact that contemporary man no longer needs to bathe in pure waters, the steam baths have been turned into a night shelter. If you can’t find a hotel room, you go to the baths. One night costs twenty marks. For that you can sweat the night away, if you like, or sleep yourself clean. The baths should have some sort of inscription. Something like: PER SUDOREM AD SOLEM! or white nights.

The men’s lounge in the Admiral Baths.

Travelers may be seen arriving from the nearby Friedrichstrasse station at midnight, with suitcases. Returned from fruitlessly making the rounds of the city’s hotels, they sigh with relief at the entrance to the baths. Slowly they have become a pivotal metropolitan institution — a bolt- and water hole for the tourist in his hour of need.

The grotesque spectacle of a hot room at night, containing sixteen naked homeless people, trying to sweat out the soot and coal smoke of a train journey, gives rise to a positively infernal range of interpretations. A series of illustrations, say, to Dante’s journeys in the underworld. The only creature permitted to be fully clothed, standing there purposefully and conscientiously with scrubbing brush and torturer’s gauntlet in hand, could quite easily be some underdevil, if you happened not to know that his infernal character will be appeased, and his true character revealed by a small tip, once you have withstood his torments.

I don’t know if people in hell look as ridiculous as they do here. If the fashion there is for them to be likewise stripped naked, then they will do, for all their grimness and tragedy. I have a feeling that the witching hour does something to exacerbate the already intrinsically comical condition of nudity. It’s such a bizarre notion that between midnight and 2 a.m. there are people being steamed.

Somebody with frail, uncoordinated joints that look as though they’d been provisionally held together with string performs swimming motions in a pool for a whole nocturnal hour. Another, a fat man, who might be advised to borrow the equator from the earth as a belt for his dressing gown, looks on with a grimly sadistic expression, until he starts to feel the chill and has to take himself to the hot pool to recoup the calories that his Schadenfreude has cost him. He cautiously extends the tip of his right big toe into the water, but it’s too hot for him. He would like to watch himself enter the water — only his belly isn’t made of glass.

The dormitory looks like a hollow polygon from geometry class. The sofas are small, low, and numerous. They stand there, as it were, guilelessly, as if, say, somebody had just left them there in despair, because there was nowhere else. People come here in their Turkish towels to try and catch a little sleep.

Only they make it impossible for one another. It is quite extraordinary what hidden desires cleanliness is able to flush out of thoroughly sweated souls. The appetite increases prodigiously. I almost think the only reason the steam baths were closed during the war was because of England’s naval blockade. Sixteen thoroughly purified men are capable of consuming at a single sitting enough food to feed a city for six months.

Oh, and if only sandwiches didn’t have to come wrapped in noisy wax paper! As if soft, silent paper wouldn’t do the job just as well! Three gentlemen who have gotten off the train ask for their bags. I hoped one of them would have the provisions for all three in his bag. I hoped, further, that hunger would appear in all three simultaneously, since they’d all arrived on the same train, and stepped out of their baths at the same time too. But they, cunning fellows, used their appetites to provoke and taunt me.

Each of the three took it in turn to open his suitcase, his little key squeaking in the lock like a young puppy dog, and then came the unwrapping, with all the lavishly variegated stages of a proper picnic lunch, as if this weren’t a steam bath at night but a green meadow on a Sunday afternoon.

Over time I grew able amply — hardly — to distinguish the three travelers from one another. One of them unwrapped his sandwiches swiftly and with decision, he didn’t rustle so much as crunch. The other didn’t crunch, but he was impatient and kept ripping his paper. The third took the longest. He folded up his paper minutely afterward. I think he must have had a long journey still ahead of him. Strange, someone taking so much trouble to make it clear to all those present that he didn’t really need to take a bath here. No, by no means. He was clean only yesterday. Who would doubt it? But an odd, enforced bath like this, for want of a hotel room, it’s not such a bad thing. And even though I’m absolutely prepared to believe that he was in a state of tiptop cleanliness when he arrived, he still won’t stop trying to convince me of the fact. He comes from the provinces. It all strikes him as terribly amusing, and I can see him working on his account for the assembled listeners in the bar — the wacky things people get up to in Berlin.

Читать дальше