These dead people are ugly and reproachful. They line up like prickings of conscience. They look as they did when they were first found, mortal terror on their faces. They stand there open mouthed, their dying screams are still in the air, you can hear them as you look. Their death agonies keep their eyes half open, the white shimmers under their eyelids. They are bearded and beardless, men and women, young and old. They were found on the street, in the Tiergarten, in the river Spree or the canals. In some cases the place where they were found is not given or is unknown. The drowned bodies are puffed up and slime encrusted, they resemble badly mummified Egyptian kings. The crusts on their faces are cracked and split like a poor-quality plaster cast. The women’s breasts are grotesquely swollen, their features contorted, their hair like a pile of sweepings on their swollen heads.

If these dead had names, they would be less reproachful. To judge by their faces and garments, they were not exactly prosperous in life. They belonged to those called the “lower classes,” because they happened to be worse off. They were laborers, maids, people who have to undertake heavy physical labor or crime if they are to live. It is unusual for one of the dead heads to emerge from a stiff collar, which in Europe is the emblem of the middle class. Almost always from open-collared shirts in dark colors that show the dirt less.

And the place where their gruesome death caught up with them, that now seems to color their entire lives. One was found on December 2, 1921, in the Potsdam Station toilets. On June 25, 1920, this woman, age unknown, was pulled ashore on the Reichstagsufer of the Spree. On January 25, 1918, that bearded, toothless head died on Alexanderplatz. On May 8, 1922, this young man with a rapt expression died, on a bench on Arminiusplatz. He must owe his peaceful countenance to that wonderful May night on Arminiusplatz. Probably a nightingale was singing when he died, the lilac was fragrant, and the stars were shining.

On October 26, 1921, a man, aged about thirty-five, was beaten to death on a piece of waste ground, somewhere off Spandauer Strasse. A thin line of blood leads from the temple to the lip, thin and red. The man himself has long since been buried, and his blood has stopped, but here in the picture it will always flow. Futile to wait for cranes, like the legendary cranes that once revealed the identity of the murderer of Ibycus. No cranes swarm over the waste ground off Spandauer Strasse — they would long ago have been roasted and eaten. God, beyond the clouds, watches the conflagration of a world war quite unmoved. Why would he choose to get involved over one poor individual?

There are perhaps one hundred photographs in the display cases, and they are continually being replaced by others. Thousands of unknown people die in the city. Without parents, without friends, they lived lonely lives, and no one cared when they died. They were never part of the weave of a society or community — a city has room for many, many lonely people. If a hundred of them are murdered, thousands live on, without a name, without a roof, like pebbles on the beach, practically indistinguishable one from another, all one day to meet a violent end — and their death has no particular resonance and never makes the newspapers like that of some Talat Pasha.

Just one anonymous photograph making its mute appeal to indifferent passersby in the police station, vainly asking to be identified.

Neue Berliner Zeitung—12-Uhr-Blatt, January 17, 1923

11. The Resurrection (1923)

A Half Century in Prison

The Berlin old people’s home is situated on the main street in Rummelsburg, where the first glimmering green of the world beyond factories just begins to show. As the name suggests, old people live there. They have set down their pasts like heavy burdens that they have successfully dragged to their final destinations. There’s not far to go now, from the old people’s home to the grave.

A good many of these old people are actually going back into care. They were institutionalized as juvenile delinquents, then were released out into the world, were picked up and sent back to where they had started. On fine evenings the oldsters sit on benches in the big park, and tell each other about different worlds, about Mexico, or Spain, or the various Capes of Good Hope that they made for in their lives, on whose rocks they beached. The old people’s home is destiny. A man can have wandered many thousands of miles in his life, but in the end he will wind up in Rummelsburg. It lies at the end of every adventurous life. You can’t escape the Rummelsburg your destiny holds for you.

There is one man living in the old people’s home in Rummelsburg, who can look back on a fifty-year death. What for others is the end, to him is the beginning. This old people’s home is, so to speak, his kindergarten. At the end of fifty years this man of seventy is facing a new world.

The man’s name is Georg B., and he was sentenced to life imprisonment fifty-one years ago for being an accessory to robbery and murder. Recently the authorities were in a good mood, and he was released and allowed to go to Rummelsburg. And, at the end of fifty-one years, he found himself back, for the first time, in the great city of Berlin.

This account of a resurrection is only possible because the extraordinary rarity of such a “case,” while not compensating for the man’s past as a violent criminal, at any rate pushes it into the background. He has been sufficiently punished for his crime, and the interesting part of his story would not have been possible without crime and without punishment.

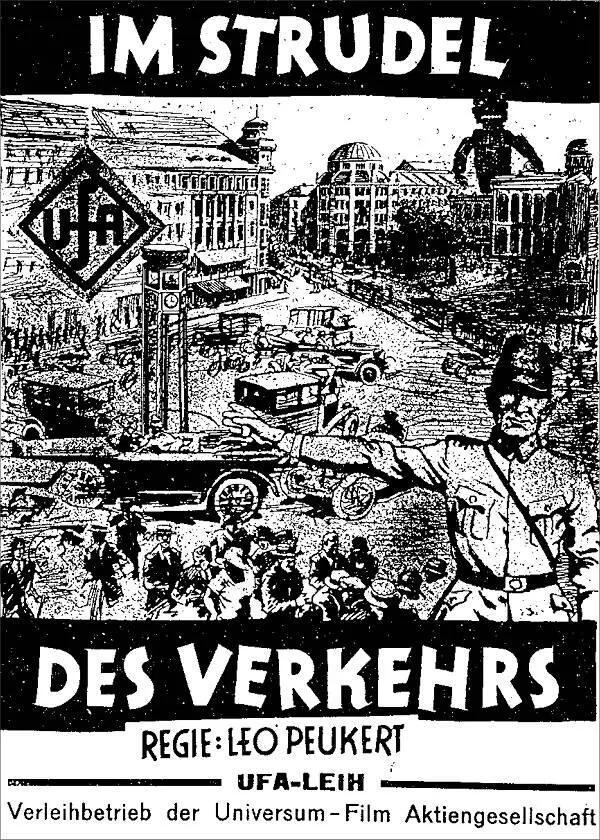

Georg B. remembers Berlin the way it was fifty years ago. If, in the course of his long life behind bars, he thought of the city at all, then he saw before him a city with horse-drawn traffic in its streets, a city that ended at Potsdamer Platz, and the clatter of a cart would have struck him as a metropolitan noise indeed. For fifty years B. carried the picture of such a city in his head. If at times he ventured to imagine progress, if he happened to read in the pages of some newspaper that had been picked up and dropped in his remote fastness, about technical innovations, then his imagination might conjure up maybe a four- instead of a three-story house, and his eye might envision, perhaps, without the incremental aid of reality, a vehicle that was capable of moving by itself. A vehicle whose speed would correspond, perhaps, with that of a carriage drawn by four, or at the most, six, horses. For what else did his understanding have to guide him than the scale of what he knew? A dray horse represented speed to him — and he had never seen a human move more nimbly than a hare, a deer, a gazelle.

Then, all at once, B. climbed out of the S-bahn, and stood in the middle of the twentieth century. Was it the twentieth? Not the fortieth? It had to be at least the fortieth. With the speed of arrows shot from a bow, like human projectiles, young fellows with newspapers darted here and there on flying bicycles made of shiny steel! Black and brown, imposing and tiny little vehicles slipped noiselessly down the street. A man sat in the middle and turned a wheel, as if he were the captain of a ship. And sounds — threatening, deep and shrill, plaintive and warning, squeaking, angry, hoarse, hate-filled sounds — emanated from the throats of these vehicles. What were they shouting? What were these voices? What were they telling the pedestrians? Everyone seemed to understand, everyone except B. The world had a completely new language, a means of communication as universal as German — and yet it was composed of anguished, shattering primal sounds, as from the first days of mankind, from the deceased jungles of the Tertiary period. One man stopped, and another sprinted, arms across his chest, cradling his life, right across the Damm. Potsdamer Platz was no longer the end, but Mitte. * A wailing hoot from a policeman’s cornet gave the orders for quick march and attention, a whole assembly of trams, cars crushing one another’s rib cages, a flickering of colors, a noisy, parping, surging color, red and yellow and violet yells.

Читать дальше