You can sleep quite well on these sofas, if your neighbors have already eaten. If you go out in the corridor, you will see a poster that tells you that it is forbidden, first, to smoke (where would you keep your cigarettes?), and second to enter the manicure room “in a state of undress.” And for all that I saw naked people leaving the manicure room.

People in a state of nature wander through the corridors of the Admiral’s Palace. The world’s highways and byways must have looked like this when the world was in its infancy, and before men’s and women’s fashion became the flourishing industry it is today.

If you go out onto the dark streets at 5 a.m., you will just catch the final farewells between men and women, and the tired homeward trudge of a Friedrichstrasse whore who’s had a bad night and is going home penniless. A truck rumbles past, it’s raining, and it’s bitter.

Neue Berliner Zeitung—12-Uhr-Blatt, March 4, 1920

Schiller Park opens its portals, quite unexpectedly, in the north of the city, a surprising gem beyond the brewery belt of the various Schultheisses and Patzenhofers: like a park in exile. It looks every bit as though it had once been situated in the west of the city, and along with its relegation, it had been stripped of its ornamental lake and its little weather hut with barometer and sundial.

What it’s left with are its weeping willows and its complement of park wardens. These are laconic and, in all probability, good people, because they follow an occupation that is not a soul-destroying one. They are the world’s only harmless police, admonitory notice boards put in place by the Almighty and the local authorities, till one day, out of boredom, they suddenly left their posts and took to ambulating up and down the leafy avenues. On their faces you can read their original, now weathered inscription: citizens, look after your amenities — and the willow wands they hold in their hands are mildly waving exclamation marks. Park wardens, by the way, are the only living beings permitted to set foot on the grass.

I have long been curious as to what park wardens do in the winter. It’s scarcely credible that they should ever leave their parks to share a kitchen with wives and children. Much more likely that they wrap themselves in straw and rags, and passersby take them for rose trees or bits of statuary, or that they dig in for the winter, and come out in the spring along with the violets and primulas. With my own eyes I have seen them feeding off hips and haws, in the manner of shy forest creatures. Ask them a question, and they will think for a long time before replying. There’s always a layer of solitude about them, as there is with gravediggers and lighthouse keepers. .

The people who live around Schiller Park work in the mornings. That’s why the park is as deserted at that time as if it were off limits. One or two unemployed men trudge past; otherwise I see no one.

Then two girls, seventeen and nature-loving, come wandering through its avenues. It’s as if birches could suddenly walk. But real birches are rooted in the ground, and can only sway their hips.

The children arrive at three in the afternoon with pails and shovels and mothers. They leave the mothers sitting on wide white benches and toddle off to the sandbox.

Sand is something that God invented specially for small children, so that in their wise innocence of what it is to play, they may have a sense of the purposes and objectives of earthly activity. They shovel the sand into a tin pail, then carry it to a different place, and pour it out. And then some other children come along and reverse the process, taking the sand back whence it came.

And that’s all life is.

The weeping willows, on the other hand, are evocative of death.

They are a little contrived, a little exaggerated, still green in the middle of all the colors of autumn, and there is a human pathos to them. Weeping willows were not created by God at the same time as the other trees, like the hazelnuts and the apple trees, but only after he had decided to allow people to die. They are a sort of second-generation tree, flora endowed with intellect and a sense of ceremony.

Even in Schiller Park the leaves drop from the trees in a timely fashion, in the autumn, but they are not left to lie. In the Tiergarten, for instance, a melancholy walker can positively wade through foliage. This sets up a highly poetic rustling and fills the spirit with mournfulness and a sense of transience. But in Schiller Park, the locals from the working-class district of Wedding gather up the leaves every evening, and dry them, and use them for winter fuel.

Rustling is strictly a luxury, as if poetry without central heating were unnatural.

The rosehips look like fat red little liqueur bottles, distributed for promotional purposes. They fall from the trees free of charge, and are collected by the children. The park wardens look on, feeling no alarm. For they have placed their trust in the Lord, who feeds the wardens in the fields and arrays them in local-authority caps.

Berliner Börsen-Courier, October 23, 1923

10. The Unnamed Dead (1923)

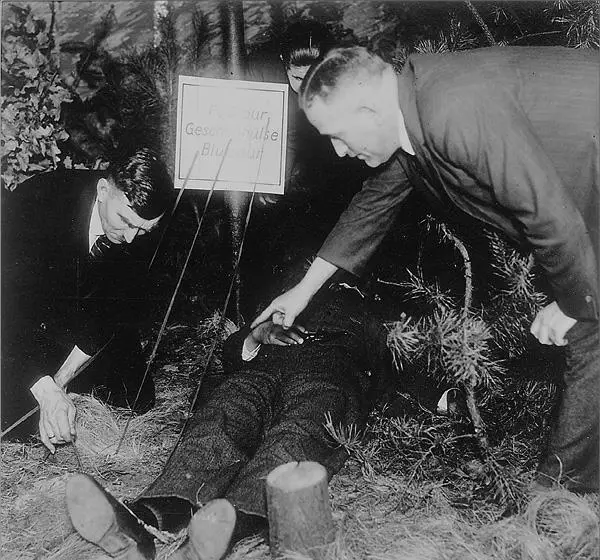

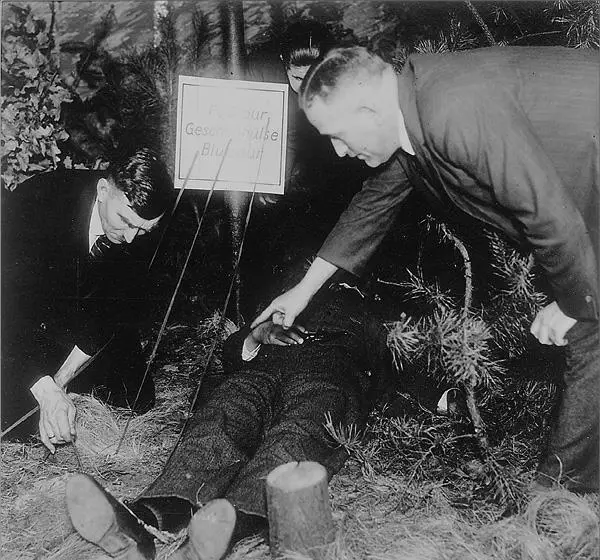

The city’s unnamed dead may be seen laid out, in tidy rows, in the photograph cabinets on the ground floor of the police headquarters. It’s a grisly exhibition drawn from the whole grisly city, in whose asphalt streets, gray-shaded parks, and blue canals death lurks with revolver, chloroform, and gag. This is the hidden side of the city, its anonymous misery. These are her obscure children, whose lives are put together from shiftlessness, pub, and obscurity, and whose end is violent and bloody, a murderous finale. They stumble unconsciously into one of the numberless graves that have been dug beside the path of their lives, and the only trace of themselves they bequeath to posterity is their photograph, snapped at the so-called scene of the incident by a police photographer.

Each time I stop in front of a photographer’s window to view the pictures of the living in their finery, the newlywed couples, the confirmees, the smiling faces, the white veils, the confetti, the rows of medals on some excellency’s breast, the sight of which seems to tinkle and jingle in the mind’s ear — I remember the case with the dead in the police station. It shouldn’t be in the corridor of the police station at all, but somewhere where it is very visible, in some public space, at the heart of the city whose true reflection it offers. The windows with the portraits of the living, the happy, the festive, give a false sense of life — which is not one round of weddings, of beautiful women with exposed shoulders, of confirmations. Sudden deaths, murders, heart attacks, drownings are celebrated in this world.

It is these instructive photographs that should be shown in the Pathé Newsreels, and not the continual parades, the patriotic Corpus Christi processions, the health spas with their drinking fountains, their parasols, their bitter curative waters, their terraces from Wagner myths. Life isn’t as serenely beautiful as the Pathé News would have you believe.

Every day, every hour, a great many people, many hundreds of people, pass through the corridor of the police headquarters, and no one stops in front of the glass cases to look at the dead. People go to the Alien Registration Office,* to the Passport Office to get a visa, to the Lost Property Office to look for an umbrella, to the Criminal Investigations Department to report a robbery. The people who come to police headquarters are concerned, in one way or another, with life, and with the single exception of your correspondent, not one of them is a philosopher. Who among them would take an interest in the dead?

Читать дальше