Boris Spassky went to Reykjavik to celebrate chess. Bobby Fischer went there to fight. His version of the match triumphed. The relics of the combat can be seen in the Icelandic Chess Federation museum, found down a Reykjavik side street, on the first floor of what looks like the run-down offices of a struggling small business. Some photographs and cartoons capture the atmosphere of the event. And there, recently reclaimed from the cellars of the National Museum to which they had been consigned, are the chessboard, signed by the contenders, the chessmen they pushed across it, and the clock started by Lothar Schmid at five P.M. on 11 July 1972 to begin the match of the century.

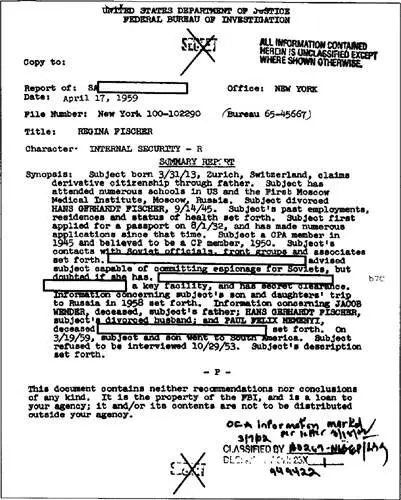

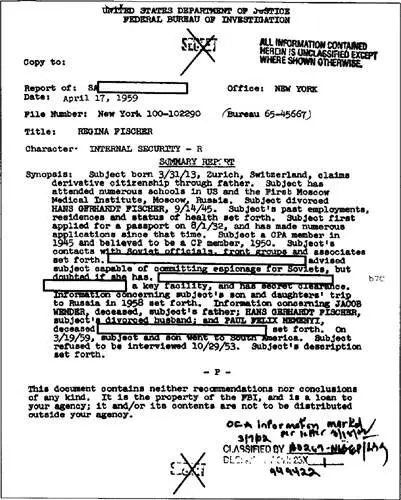

We have mentioned Regina Fischer, Bobby’s mother, only in passing. The FBI suspected that she was a Soviet agent. The Bureau’s files, the fruit of three decades of surveillance, present a fascinating portrait of a woman possessed of extraordinary force of character and unconventional attitudes. They also tell of the secret at the heart of her family.

Regina’s parents were of Polish-Jewish origin. Her father, Jacob Wender, was a dress cutter by profession. The family had moved first to Switzerland, where Regina was born on 31 March 1913, and then, when she was only a few months old, to St. Louis in the American Midwest. Her mother, Natalie, died when Regina was ten; Jacob married Ethel Greenberg, with whom Regina did not get along. Jacob and Regina were naturalized as Americans on 12 November 1926.

After graduating from high school in St. Louis, Regina attended Washington University, the University of Arizona, and the University of Denver. In 1932, nineteen years old and without a degree, she went to Berlin to study and to work as a governess. There she fell in love with Gerhardt Fischer, five years her senior; he was also known by another name, Gerardo Liebscher.

In early 1933, the couple made the decision to uproot to Moscow. Regina claimed later they had done so to get married: Of course, with the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, she might have felt increasingly uncomfortable there. But that Russia was the chosen destination probably indicates the true reason for their leaving Germany. Gerhardt was a communist. He might even have been a Comintern agent.

In any case, they married in Moscow on 4 November 1933 and lived on in the city for five years. Their daughter, Joan, was born there in 1937. Regina studied at the First Moscow Medical Institute. Gerhardt was associated with the Moscow Brain Institute. For some of the time, they occupied apartment 42 at Zemlianoi Val 14/16, in a neighborhood of substantial Stalin-era apartments, with big living rooms and kitchens. Their choice of refuge from Nazi power scarcely offered peace and security; this was the height of the Great Terror. But unlike many other foreign communists who sought sanctuary in the Soviet Union, Gerhardt was not among Stalin’s victims.

Toward the end of that five-year period, there is evidence that the marriage might have become rocky. When Regina went to renew her passport at the American embassy on 29 July 1938, she informed a member of staff that she had separated from her husband. But this could well have been a cover-up. It is likely that Gerhardt had left (or been sent) to operate on the Republican side in the Spanish civil war.

Regina departed for France later that year, meeting up with Gerhardt in Paris (whether he arrived in France from the USSR or Spain is unclear). Peace in Europe was looking increasingly uncertain, and Regina was now determined to return to the United States: She did so on 23 January 1939. Gerhardt, who did not have a U.S. passport, stayed on in Europe; he had somehow managed to acquire a Spanish passport, number 5999, evidence of his involvement in civil war Spain. But it remains a mystery why he was denied access to the States when he was married to a U.S. citizen. In any case, on 4 January 1940, he landed in Chile, where he eventually set up a shop selling and installing fluorescent lighting, and dabbled in photographic work.

Until Bobby was seventeen, Regina was omnipresent in his life. What she almost certainly did not know, and what Bobby could not have known, is that the family was closely monitored by the FBI, which amassed a nine-hundred-page file on her. The dossier reveals that some factual details routinely offered in biographical accounts of Bobby’s early life are wrong.

Regina was first brought to the attention of the FBI on 3 October 1942, when she was working as a student instructor at the U.S. Air Force’s Radio Instructors’ School at St. Louis University. She expected her second child the following March. Regina was financially desperate, so much so that, through a Jewish charity, she attempted to place her daughter, Joan, with another family.

FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION

The arrangement quickly collapsed, the foster mother asking Regina to take Joan back. The woman did not tell Regina that she had contacted the authorities. America was at war. She had discovered some “suspicious” items and documents among belongings Regina had left with Joan and considered that these posed a potential threat to the “national welfare.” The suspect possessions included several pages of scribbled “chemical formulas,” [sic] as well as a B-2 Cadet camera with a state-of-the-art lens and a collapsible umbrella. There was also a letter from a left-wing friend that included the sentence, “Washington is really a fascinating city, although right now it is getting too hot for comfort.” The woman considered it worthy of note that Regina owned “a heavy black rubber apron and two heavy rubber sheets.”

So began an operation lasting two decades and costing tens of thousands of U.S. government dollars, though there were perfectly plausible explanations for the items Regina left among Joan’s belongings. After returning to the United States, Regina had completed her BA degree at the University of Denver, where she majored in French, German, biology, and chemistry. The last would account for the “chemical formulas” and perhaps the rubber sheet and gloves. As for the camera and collapsible umbrella, her absent husband, Gerhardt, was a professional photographer.

Although the evidence was circumstantial, the FBI came to believe Gerhardt was something more sinister—that he was a Soviet agent. Why did he spend those years in Russia? Why did he have that mysterious Spanish passport? In Chile, had he not joined the Communist Party and fraternized with fellow left-wingers? But most significant of all, in the eyes of the FBI, was a letter also found among Regina’s belongings in 1942. It had been posted in June 1941 and was written in a stilted style; the FBI described it as “cryptic” (though English was not Gerhardt’s mother tongue). In the letter, Gerhardt explained how he had taken pictures of fishing boats and fishermen at the port of San Antonio about an hour and a half west of the capital, Santiago. The FBI observed that at the same time, three Germans, posing as fishermen at the port, were charged with transmitting espionage information by radio.

If Gerhardt was a Soviet agent, what about his wife? It made no difference to the FBI that Regina was granted a divorce from Gerhardt on 14 September 1945 on the grounds of willful neglect to provide for her and their two children—she had received no financial support since July 1942. (At the time, she was living in Moscow, Idaho. The local paper, the Daily Idahonian, had fun with the story—married in Moscow, divorced in Moscow.)

The FBI files contain half a dozen physical descriptions of Regina; one from this period states that she was five feet four, with dark brown hair, dark brown eyes, thick eyebrows, full lips, olive complexion, heavy legs, a low and heavy bust, and a “scruffy” appearance. Her nose features in another description—long and “a little crooked.”

Читать дальше