David Robbins

WAR OF THE RATS

A NOVEL OF STALINGRAD

NOT EVEN NAPOLEON HAD STABBED AS DEEPLY INTO Russia as the German army had by August of 1942.

Adolf Hitler’s forces plunged one thousand miles across the vast and hostile plains of Russia to the banks of the Volga River. It was by far the deepest penetration into this Asian land of any foreign legion in history.

The German plan was simple: place Moscow under siege to tie up precious Russian defenses, then race south into the Caucasus region and conquer the strategic oil fields there. Once in control of the Caucasus, Hitler could fashion a peace on his terms and divide Russia in half, enslaving the western portion of the huge nation for his dream of Aryan world expansion and “one thousand years of Nazi rule.”

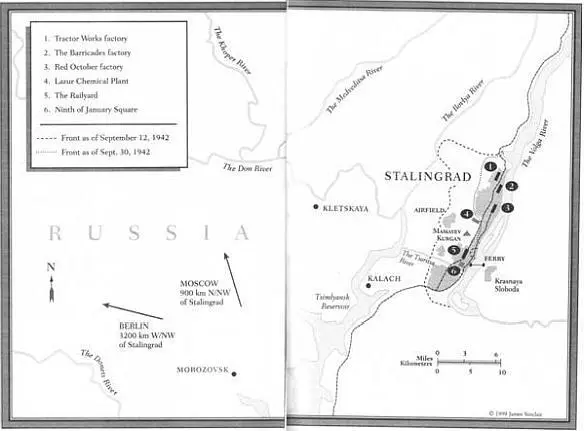

Late in July of 1942, Hitler called for a temporary shift in the Schwerpunkt, or main weight, of his Russian invasion, away from the southern oil fields to drive eastward, to neutralize a potential canker on his left flank. The city of Stalingrad, an industrial center responsible for almost half of Russia’s steel and tractor production, a metropolis of over 500,000 residents, lay on the banks of a crescent in the Volga. Hitler sensed an important, and easy, victory.

The legacy of that decision was written thereafter in more blood and destruction than any other battle in history. The Red forces, under strict instructions from Stalin (for whom the city, formerly Tsaritsyn, was named in 1925 in gratitude for his role in defending it from the White forces during the Russian civil war) to take “not a step backward,” put up an unexpected and vicious fight.

Stalingrad’s five-month trial by fire began on August 23, 1942, when the first panzer grenadiers of the German Sixth Army reached the Volga on the city’s northern outskirts. The German forces were under General Friedrich Paulus. He and his Russian counterpart, General Vasily Chuikov, commander of the Red Army’s Sixty-second Army, presided over a terrible battlefield. The city, subjected to intense firebombings in late August, became a smoking charnel house. Soldiers fought and died in cellars, hallways, alleys, and the massive labyrinths of the wrecked factories smoldering beside the river. For months, the fighting was house to house and hand to hand, and the front lines swayed with each new clash, the rewards of which were measured in meters at a time. German foot soldiers called the fighting Rattenkrieg. War of the Rats.

The Sixth Army kept its strength inside the city at close to a hundred thousand troops, drawing on reserves of over a million men from German, Italian, Hungarian, and Rumanian divisions positioned on the great steppe outside Stalingrad. The Red force inside the city never exceeded sixty thousand soldiers and at times was as low as twenty thousand men desperately surviving until reinforcements could be ferried across the Volga. The two armies ground against each other with an incredible will, killing and maiming soldiers in unprecedented thousands.

By mid-October the Russians had their backs literally to the river. In some places they hunkered no more than a hundred yards from the Volga cliffs. Somehow they held out until finally, on November 19, 1942, the Red Army sprang its “November surprise.” The Russians executed a sudden and immense flanking action that leaped out from both the north and south to close with terrifying speed behind the Germans and their allies, encircling them with a million and a half vengeful men. Hitler called his surrounded Sixth Army “Fortress Stalingrad” and told the world these men would stay in place and fight to the death. His encircled troops, freezing, starving, bedeviled by lice, and under constant threat of Russian attack, called their position der Kessel, “the Cauldron.” Of the quarter of a million soldiers surrounded on the steppe in mid-November, less than a hundred thousand were alive to surrender two and a half months later.

The city’s ordeal ended on January 31, 1943, when Paulus, a starved wraith of a man with a facial tic and a dead army, walked out of the battered Univermag department store in the decimated center of the city and surrendered.

The final toll on both armies was an estimated 1,109,000 deaths, the high-water mark of human destruction in the annals of combat. The Red Army reported 750,000 killed, wounded, or missing. German casualties were 400,000 men. The Italians suffered a loss of 130,000 out of their original force of 200,000. The Hungarians saw 120,000 killed, the Rumanians 200,000. Out of a prewar population in Stalingrad numbering more than 500,000, only 1,500 civilians were alive there after the battle.

For both armies, the outcome of Stalingrad was pivotal. Never before had an entire German army disappeared in battle. The Nazi myth of invincibility was broken. The Reds now had a major victory; Russia had withstood Hitler’s best punch, and returned to him a death blow. Stalingrad was as far as the Nazis got; the Germans fought a rearguard action for the remainder of the war. Two years later Red forces were celebrating in the streets of Berlin.

* * *

INTO THE MIDST OF THIS AWFUL CARNAGE, PLAYED OUT on this pivotal stage, strode two men: Russian Chief Master Sergeant Vasily Zaitsev and German SS Colonel Heinz Thorvald.

Each was reputed within his own army as its most skillful killer, a master sniper of extraordinary abilities. Both were assigned to find and destroy the other. Each knew his nemesis was looking for him in the colossal maze of ruin and death that was Stalingrad.

Three of the four principal characters in War of the Rats —Zaitsev, Thorvald, and the female sniper Tania Chernova—were actual combatants at Stalingrad. Their escapades and those of several of their comrades have been documented in a number of works of history, and this novel has been drawn from those works (see Bibliography). While Zaitsev’s personal and family histories are recounted faithfully, I have presented the backgrounds of both Thorvald and Tania with some details imagined or altered for dramatic purposes. But the German sniper’s and the female partisan’s adventures and fates in Stalingrad have been left unchanged. The fourth character, Corporal Nikki Mond, is a composite German soldier who lives as authentic a life in Stalingrad as could be devised for him.

The dates, troop movements, and major battle details in War of the Bats are historical fact. In addition, most of the smaller vignettes, the personal struggles and interactions, are also fact, gleaned from interviews with survivors as well as written accounts. But like any novel, here—in the smaller, private moments—creep in the notions of accuracy and legitimacy. It is, of course, impossible to describe another’s thoughts and unseen acts. It is possible, however, with study and understanding, to re-create what an individual might have done and how he or she might have gone about doing it in a manner that, while fictional, remains genuine.

DLR Richmond, Virginia

ONE

THE CORPORAL, THE HARE, THE PARTISAN, AND THE HEADMASTER

NIKKI MOND LOOKED OUT OF THE TRENCH INTO A smeared gray dawn.

The first light of the late October sky stayed clenched in a fist of smoke and dust. Fires from the night’s bombing chattered in the rubble. Burned tanks and trucks smoldered on the front line four hundred meters away, pulsing greasy oil smoke. Brick and concrete dust put a dry, chalky taste on every breath.

Читать дальше