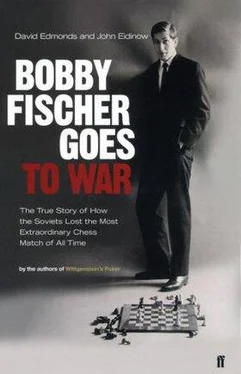

To reenergize chess and to free it from the oppressive body of theoretical knowledge built up over decades, Fischer now advocates random chess, in which the pieces on the back row are shuffled at the beginning of each game. Random chess would force players to clear their minds of preparatory work and think about each game afresh. Fischer dreams of another Spassky rematch—this time at random chess. Spassky told the authors of this book that he would agree to one, “just for fun.”

Reykjavik changed chess itself. In the immediate aftermath of the 1972 match, a sudden fascination for the game brought salad days for the chess masters. Publishers sought them out to satisfy the appetite for information: A huge array of books appeared, from those targeted at the complete beginner to those aimed at the already accomplished. There were books on openings, books on the middle game, books on endings. There were books on tactics and books on strategy, books on how to beat the patzer and a book on how to beat Fischer. A number of instant books were released on the match. The first, by David Levy and Svetozar Gligoric, was on its way to the printing presses before the result had been officially declared, and went on sale in New York stores within twenty-four hours of the declaration. Gligoric had penned his final sentence immediately after his good friend Lothar Schmid let slip that Spassky had resigned by telephone. The one-hundred-thousand print run sold out rapidly.

The chess phenomenon was such that grandmasters, and even international masters, could now make a decent living. The prize money shot up for competitions; cash was to be earned from giving simultaneous matches, from writing, from coaching. Edmar Mednis turned professional along with several other top players. “During the first year subsequent to the match, it was as though money were falling from heaven.”

Soon after Reykjavik, San Francisco promoter Cyrus Weiss floated the idea of a professional chess major league, in which five teams across the United States would compete against one another in a series of televised matches. At the time, this seemed far from quixotic. Chess was entering the nation’s sporting bloodstream. A decade earlier, the U.S. Chess Federation had fewer than 10,000 members. Now there were over 60,000 and the rate of growth appeared to be carrying the numbers into orbit.

A generation of youngsters was stimulated to take up the game. The rise of Britain as a chess powerhouse can be traced back to Reykjavik. Nigel Short, who one day would challenge Garry Kasparov for the title, decided then, at age seven, that he would become a professional.

The match itself inspired the (then) most expensive musical ever staged, Chess, written by Tim Rice and the ABBA partnership of Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus. The idea for the musical had occurred to Rice shortly after Fischer’s victory: “The good guy was the Russian, who was meant to be the bad guy, and the bad guy was the American, who was meant to be the good guy. It was all very confusing and a perfect illustration of how politics creeps into everything.” His lyrics reflected this:

The value of events like this need not he stressed

When East and West

Can meet as comrades, ease the tension over drinks

Through sporting links

As long as their man sinks.

Again, this cold war aspect was singled out by a 1980s British pop group, the critically acclaimed Prefab Sprout, in their song “Cue Fanfare”:

The sweetest moment comes at last—the waiting’s over,

in shock they stare and cue fanfare.

When Bobby Fischer’s plane touches the ground,

he’ll take those Russian boys and play them out of town,

playing for blood as grandmasters should.

However, in America, at least, the explosion of interest did not endure as long as the cold war. Although grandmasters have never quite returned to their earlier levels of impoverishment, within a few years the enthusiasm of promoters had begun to subside, and sponsorship money for tournaments to dry up. And just as Fischer had been primarily responsible for the boom, so, by disappearing from the scene, he was principally responsible for the bust.

Apart from Fischer, none of the Western participants benefited materially. Palsson was left financially worse off than before, though his house is rich in bulging scrapbooks. Paul Marshall never received a dime: “I guess being involved in such an intimate way in what turned out to be a world-shatteringly silly event, and the fact that it was good for dinner party conversations for the rest of my life, was probably enough of a fee.” Gudmundur Thorarinsson went on to serve as a member of Parliament for two terms—but failed to scale the political heights to which he had hoped the match would take him. Nevertheless, more than three decades on, he is still starry-eyed over the event he brought to Reykjavik: “People say this was the chess match of the century. It was not the chess match of the century. It was the chess match of all time.”

Beyond the legend, what we are left with, of course, are the games. As one would expect from a clash between the two preeminent players of the day, several were of extraordinary brilliance, artistic creations that will be with us always. One thinks, for example, of the magnificent game ten, apparently so effortless, so economical, so unshowy—yet so beautiful. There were also some staggering howlers, a function of the inhuman stress affecting both players: Bxh2 in game one (Fischer), Qc2 in game five (Spassky), pawn to b5 in game eight (Spassky), pawn to f6 in game fourteen (Spassky). Works of art are usually the product of a single guiding mind and hand. A chess masterpiece is the product of competing genius: Crass blunders from either side can disqualify a game from true greatness. But Spassky’s errors and defeat must not be allowed to obscure the fact that he was one of the finest players of all time. In his career, he could boast match-play victories against some of the totemic chess names of the second half of the twentieth century—Keres, Geller, Tal, Larsen, Korchnoi, and Petrosian.

Fischer, some will maintain, was the outstanding player in chess history, though there are powerful advocates too for Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, and Kasparov. Many chess players will dismiss such comparisons as meaningless, akin to the futile attempt to grade the supreme musicians of all time. But the manner in which Fischer stormed his way to Reykjavik, his breathtaking dominance at the Palma de Majorca Interzonal, the trouncings of Taimanov, Larsen, and Petrosian—all this was unprecedented. There never has been an era in modern chess during which one player has so overshadowed all others.

Our story is in essence a tragedy. What could have been the feast of chess anticipated by Spassky is as much remembered for the pathologically manipulative behavior of the challenger, the panic of the officials, and the psychological collapse of the champion, as for the quality of the games.

While we may sympathize with the organizers and the manifest and manifold pressures upon them, the game three capitulation to the challenger can be seen as their moral tragedy. Had they not been impelled to give way to Fischer, Spassky might have left Reykjavik early, and as champion. On the other hand, had Spassky himself not been so fixed on playing Fischer, had he been a little less of a free spirit and a little more willing to work with the authorities, he might have left Reykjavik on his own initiative, and as champion.

Fischer’s life testifies to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s proposition that “there are no second acts in American lives.” Achieving his only goal destroyed his raison d’être. Without that goal, he seemed to lose his already weak hold on reality. With nothing more to prove, fear of defeat prevailed over his desire to play. Fischer turned Reykjavik into a battleground, and the match would be the last real chess war he would ever wage.

Читать дальше