The conviction that Fischer’s team had taken stringent security precautions served to heighten Soviet paranoia that the champion was being got at—the only possible explanation for his not being himself, not being on form. Geller later remarked on the Americans’ preparations for the match: “They had a technical team. What did they need this for? They had a psychological team, a security service, an information service.” Larisa Spasskaia is not the only Russian who says she remembers Fischer’s house being encircled by armed U.S. Marine guards.

This was not so. The American records reveal that Fischer’s people requested marine guards and the request was summarily turned down by the U.S. chargé d’affaires in Reykjavik, Theodore Tremblay. He loathed Fischer’s discourtesy, was embarrassed by it, could not wait for him to get off the island, and had deliberately kept embassy assistance down to a minimum in the face of Fred Cramer’s attempts at intimidation. Cramer had warned that he would take matters all the way to the White House. Tremblay had prayed that the “damned thing” would not come to Reykjavik at all because of the trouble Fischer might cause for the Icelanders. “I had no doubts they—the Icelanders—could handle it. But Fischer even before the match had quite a reputation, which even I as a non—chess player was aware of, and I could just see problems ahead.” When Fischer’s praetorian guard arrived and demanded that the embassy help financially, Tremblay had a cast-iron defense: “I wasn’t inclined to be very cooperative with any of these people, and frankly it didn’t matter to me what they threatened. Indeed, I had been instructed by the State Department not to spend one cent of American taxpayers’ money on Bobby Fischer, since he had been so disrespectful of everything. So that was the way it was.”

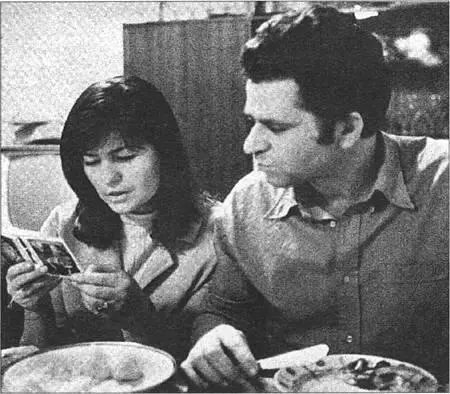

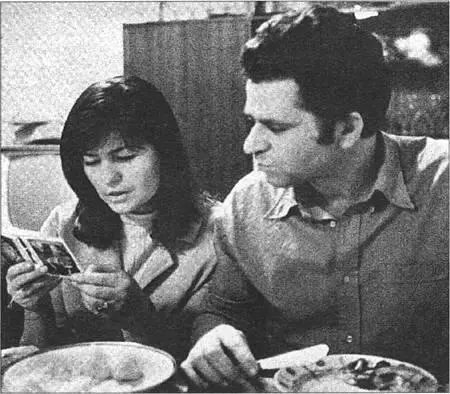

Larisa Spasskaia reunited with Boris. He feared his food was tampered with, but home cooking is safe cooking. TASS

However, the Soviet “recollections” are significant, showing the depth of insecurity and suspicion that USSR citizens carried everywhere they went. The idea that extra-chess means were used against the team in Reykjavik runs like a threnody through the postmortem four months after the match, albeit in a minor key, perhaps because the participants had more immediate, personal scores to settle. Stalinism had left the people of the Soviet Union permanently on the lookout for conspiracy, internal and external, and for culprits, someone to blame. The KGB handbook for its employees, The KGB Lexicon: The Official Soviet Intelligence Officer’s Handbook, states that “the political vigilance of the Soviet people is represented by their unfailing mindfulness of possible dangers threatening the country.”

This vigilance existed even prior to the match, as evidenced in the official report to the Sports Committee on Spassky’s preparation, drawn up on 16 October 1971 by Viktor Baturinskii. In the report, he warned that the Americans would try to hold the match on the American continent, conferring on Fischer “certain advantages.” The report went on:

Furthermore, in connection with the results of Fischer’s matches against Taimanov, Larsen and Petrosian, there has been some conjecture about the influence on these results of non-chess factors (hypnosis, telepathy, tampering with food, listening in on domestic analysis, etc.).

In the wake of Taimanov’s crushing defeat, his team manager, Aleksandr Kotov, raised the issue of external, non-chess influences on Spassky: “It appears that this has happened before. At the Taimanov-Fischer match, I had the feeling the whole time that people were eavesdropping on us.”

Mikhail Botvinnik also mistrusted the Americans; he thought Spassky should not play in any country in which there was an American base. That was why he recommended against Iceland. An electrical engineer with an early and passionate interest in computer science, Botvinnik feared baleful computer manipulation of Spassky and help to Fischer—presumably controlled by U.S. military intelligence facilities. When Reykjavik was confirmed as the match site, some Sports Committee officials even suggested a Soviet ship should be moored there, on which the Soviet team could live in a security cocoon. That idea did not progress beyond the committee’s offices, probably just as well for Spassky’s blood pressure.

Then, during the match itself, otherwise rational Soviets were alarmed by the way Spassky was prone to error and threw away promising positions. Were there sinister explanations, hypnotic rays, parapsychology, chemicals?

Once back in Moscow, Spassky himself questioned his mental state over the chessboard. “Can it really be that my chess powers fell so sharply only as the result of some small incidents and confusion? Can my psyche really have been so unstable? Either my psychology was made of glass or there were external influences.” Before we shrug our shoulders in amused disbelief, we should recall Soviet use of toxicology against opponents. When the KGB wanted to bug the apartment of Colonel Oleg Penkovskii, whom they suspected of spying for the British, they smeared a poison on his chair that sent him briefly to hospital. Why should others not have access to the same technology?

Of course, not all the Soviet insiders were disposed to blame Spassky’s apparent loss of form on American dirty tricks. But even those who dismissed the possibility of an “outside agency” charged Fischer with using non-chess tactics—that is, psychological warfare. Spassky’s trainer and second, Nikolai Krogius, was head of the Psychology Department in Saratov University as well as a grandmaster. Looking back, he gives this diagnosis:

The psychological war waged by Fischer against Spassky and his (Fischer’s) attempts at self-assertion (by crushing the will of the other player) were linked; they were two sides of a single process of struggle against Spassky…. Note that in the 1970s Fischer began to place great significance on the psychological aspects of the game. He would openly declare that he was trying to crush the will of his opponent. To this end, all means were justified. In Fischer’s opinion, the psychological subjugation of the opponent inevitably led to a reduction in the strength of the opponent’s game. Fischer carried out such a program consistently, both before and during the match.

In the Sports Committee, too, Fischer’s mind games were seen to be at the root of Spassky’s problems. The committee considered the possibility of hypnosis as early as the beginning of August but dismissed it. The former women’s world champion, Elizaveta Bykova, claimed to Viktor Ivonin that Fischer had a telepathist among his lawyers. This was not true. In any case, the committee did not believe in telepathy.

From Reykjavik, the Soviet ambassador had complained to the Sports Committee that the press, Soviet as well as Western, misrepresented Fischer when they wrote of his “eccentricities.” They were not such, he said, but deliberate, well-planned nonsporting techniques to undermine the champion. In Moscow, they analyzed Fischer and concluded that he was a psychopath, a personality for whom the norm was a conflict situation—something with which Spassky could not cope.

The crisis for Spassky was caused, they concluded, by his inability to manage the psychological pressure. This conveniently dovetailed with criticism of his refusal to accept a leader for the delegation. After the match, Viktor Baturinskii put his view roundly: “If we are talking seriously, then we should not regard external factors as the most important, especially since we have no proof.” However, driving home his point that Spassky was wrong not to have had a proper team (in other words, one that might have included a KGB translator or doctor), he hedged his bets: “The question of whether certain chemical components were introduced into the food is another matter. The delegation was warned about this. We sent Comrade Krogius especially to Reykjavik for several days to explore the security issues. We offered to send a cook, a doctor. But all this was refused by Spassky.”

Читать дальше