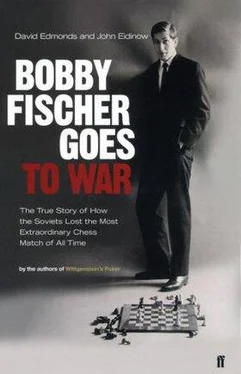

The following day, there was an audience of 2,500 people, some of whom had arrived early to guarantee a good seat and all of whom had paid $5 in the expectation of witnessing an exciting denouement. Fischer bounded in late, looking confident but, surprising for one who normally took care to appear impeccable, dressed in a hastily selected and still unpressed blood-red suit. For a change, Spassky’s seat was the one empty.

Two hours earlier, at 12:50 P.M., the champion had put in a call to the arbiter Lothar Schmid. He officially informed Schmid of his resignation; he would not go to the adjourned session. Schmid had had to phone Euwe: Could he accept a resignation by telephone? Euwe ruled this was permissible. Fischer was not informed and might not have found out until later, had the Life photographer Harry Benson not bumped into Spassky at the Saga hotel as the now ex-champion was on his way out for a walk. There followed a flurry of calls. Benson rang Fischer, who rang Schmid, insisting that, if true, this resignation must be put in writing. Schmid wrote something out himself but said Fischer would still have to show up at the scheduled hour for the adjourned session.

The match was over.

This was no grand finale, no knockout punch sending the champion to the mat, no winning hit into the stand or breasting of the tape. There were no hats thrown into the air, no stamping or cheering. This was the way the crown passed, not with a bang but a formal announcement. Once Fischer had arrived, Schmid walked to the front of the stage and addressed the hall: “Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Spassky has resigned by telephone.” Polite applause broke out around the room. The spectators had seen no action for their entrance fee, but they were witnesses to chess history. The new world champion gave a gawky wave but rejected Schmid’s proposal to take a bow. The Italian daily Corriere della Sera severely disapproved of Spassky’s nonappearance: “He missed the salute he deserved. But he no longer deserves it. One should fight until the end. It is the law of sport, and he has betrayed it.”

Icelandic government cars were parked in front of the hall alongside the U.S. ambassador’s car. Victor Jackovich was also waiting there.

It was all a ploy, because Fischer did not want to talk to anyone or be accosted by the press. So the plan was that he would come out of the side door and hop into my car—a pretty nondescript yellow and black Ford Maverick. I had been told, “Don’t stop for anybody. As soon as he gets in, just take off for the base.” So I drove him to the base, where he had a celebratory steak and a glass of milk, it was always a glass of milk. I don’t recall him being jubilant; he was a bundle of nerves, still high like a sportsman at the end of a game. It was the same Fischer I’d always taken to the base.

In victory, Fischer was at least magnanimous about his defeated opponent. Spassky was “the best player” he had met. “All the other players I’ve played crumpled at a certain point. I never felt that with Spassky.” President Nixon sent Fischer a telegram of congratulations. Spassky himself gave some interviews. He looked exhausted and said he needed to “sleep and sleep and sleep.”

The New York Times deployed Nietzschean rhetoric in their investigation of what they called “the aura of a killer.” “Basically the Fischer aura is the will to dominate, to humiliate, to take over an opponent’s mind.” It was uncanny, they pointed out, how players defeated by Fischer never fully recovered. A loss to another opponent could be excused away, put down to a bad day or a rare oversight. “But a loss to Fischer somehow diminishes a player. Part of him has been eaten, and he is that much less a whole man.” Fischer was guilty of serial “psychic murder.”

For their part, the Soviets were asking whether Fischer was guilty of other crimes.

20. EXTRA-CHESS MEANS AND HIDDEN HANDS

Sniff out, suck up, and survive.

—KGB MANTRA, CHRISTOPHER ANDREW AND OLEG GORDIEVSKY

It is striking how, to this day, some Soviet participants believe dirty tricks played a part in Spassky’s defeat.

It is striking how, to this day, some Soviet participants believe dirty tricks played a part in Spassky’s defeat.

On arrival in Iceland on 10 August, Larisa Spasskaia was conscious of the overwrought atmosphere in her husband’s suite on the seventh floor of the Saga hotel. With the wives of his team members, she had left Moscow at a time when a heavy brown haze covered the city from the heathland fire that had been steadily creeping toward the suburbs for more than a month, engulfing thousands of acres. It had reached to within fifteen miles of the suburbs and had taken the military as well as firefighters to control it. So dense was the smoke that their flight had been switched to the domestic airport, Vnukovo, because planes could not depart from the international airport at Sheremet’evo.

The Boris she encountered in Reykjavik shocked her. That day, Spassky was defeated—a massive psychological knock after his victory four days earlier that finally seemed to have stalled Fischer’s momentum. “He looked lost and strained, his nervous system out of order.” The immediate problem was the accommodation. “For Boris, the whole atmosphere in the Saga was difficult. There was something unhealthy about it; it depressed him. He couldn’t sleep and became very irritable. His mattress irritated him. Perhaps there was something in it.” This had nothing to do with the champion suffering an allergy to its composition. The dark suspicion was of a substance planted to affect his nerves.

Larisa was not alone in suspecting mischief afoot. “Geller was sure that somebody entered their rooms in their absence. Someone from the American camp. Our team was very naive. Geller left his notes for the games in his suitcase—when he opened it, he saw that everything was in a different order. He had a sealed box with a special medicine from bees, Royal Jelly. Once when he came back, the box was open. Someone had taken a pinch.”

On returning to Moscow ten days later, Geller’s wife, Oksana, reported her husband’s worries to the authorities, telling them that the score was not a reflection of Spassky’s chess ability. “Their misfortune was not a chess misfortune.” She informed them that her husband had lost eight kilos and that Spassky felt as though his mind was in a fog. Something was up with Nei, too. He had become inert, lethargic. Because of this lassitude, he had basically withdrawn from the preparations.

Mistrust was not confined to conditions in the hotel. According to Larisa, “Boris believed things were happening that were surprising and worrying. All of a sudden, in the first or second hour of the day, he would feel drowsy. At first, he thought he must have eaten too much. He cut down on the food and just took snacks, but still he was sleepy. Twice when he left for the game, his pulse rate was normal, measured at sixty-eight to seventy, and within an hour he was in a state of prostration. He couldn’t drink the coffee or juice supplied to him for fear it had been spiked.”

After spending a few days in the embassy, Larisa and Boris moved into a house in the country, ten kilometers from Reykjavik. The Soviet ambassador Sergei Astavin had arranged it for them. “We managed to escape,” is how Larisa puts it. Owned by the hotel, it resembled a dacha. There her husband slept well for the first time in weeks. His eyes became brighter and he started to talk in his normal lively manner. He also began to take more heed of Krogius and Geller, whose advice he tended to dismiss when he was wound up. Helped by the embassy cook, Vitali Yeremenko, a great admirer of Spassky as a man as well as a chess player, Larisa took care of the meals. “First I made them lunch, then a thermos of coffee and a flask of juice.” She squeezed fresh oranges, a pleasing change from the sickly sweet ersatz version in Moscow. “With those two flasks, he went to the match.” She adds, “He had never been this disturbed before. There was nothing like it in other matches. Nothing like it.” Larisa Spasskaia has a technical background; she is highly educated, an engineer by profession. She is not a woman susceptible to idle speculation. Yet to this day she is convinced that psychotropic drugs were used against her husband. “I don’t know how they did it, but I’m sure there was something. Maybe it was a special light; maybe it was in the hall, in the food.”

Читать дальше

It is striking how, to this day, some Soviet participants believe dirty tricks played a part in Spassky’s defeat.

It is striking how, to this day, some Soviet participants believe dirty tricks played a part in Spassky’s defeat.