A similar consolidation was occurring in the illegal drug business during the late 1990s. Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, the American narcotics market was split between the competing interests of the Colombians, the Mexicans, the Nigerians, the Vietnamese, and the Filipinos, among others. By 2003, 85 percent of all the illegal drugs sold in the United States—whether meth, cocaine, heroin, or marijuana—were controlled by the five DTOs, each of which controls at least one major port of entry with the United States.

The simultaneous growth of these two businesses had remarkable and tragic consequences for the modern meth trade between 1987 and 2003. Had DEA forced more oversight of the rapidly deregulating pharmaceutical industry—one that is hallmarked by its production of cold medicine—the DTOs would never have had access to the drug they needed in order to make meth. Had the DTOs not been able to make meth, it’s less likely that they would have so thoroughly monopolized the U.S. drug market.

One might ask if the drug companies should really have been made to monitor their imports simply because cold medicine happens to be made from the same drug as methamphetamine. It’s a question that lobbyists like Allan Rexinger made a career of asking. It’s also one that needn’t ever have been posed. For, beginning over a decade ago, American pharmaceutical companies could have chosen to make cold medicine from something other than pseudoephedrine.

According to Suo, in 1997 a research team at the University of North Texas began testing a new nasal decongestant in dogs and rats. The team was in the employ of Warner-Lambert, which the year before had taken over the manufacture of Sudafed and Actifed from Burroughs Wellcome and added those lines to Warner-Lambert’s highly profitable antihistamine, Benadryl. By then, Sudafed’s brand recognition was so widespread that the product, like Xerox to both photocopies and the machines that produce them, had become synonymous with the industry of cold remedies. All three nonprescription medicines—Sudafed, Actifed, and Benadryl—relied on pseudoephedrine for their manufacture. Fearful that pseudoephedrine would come under federal control, or worse, that it would be outlawed completely by legislation being pushed by Gene Haislip and DEA, Warner-Lambert had developed a new product based on a biochemical technology called mirror imaging. By Christmas of 1997, according to interviews published in the Oregonian , trials on dogs and rats at the University of North Texas showed great promise for the drug.

Mirror imaging is a process whereby a chemical’s molecular structure is reversed, moving, for example, electrons from the bottom of a certain ring to the top, and vice versa. Pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, and methamphetamine are already near mirror images of one another. To make meth from ephedrine, it is necessary to remove a single oxygen atom from the outer electron ring. Thus ephedrine and methamphetamine not only look the same under a mass spectrometer, but both dilate the alveoli in the lungs and shrink blood vessels in the nose—hence ephedrine’s use as a decongestant—while raising blood pressure and releasing adrenaline. The key difference is that meth, unlike ephedrine, prompts wide-scale releases of the neurotransmitters dopamine and epinephrine.

What the 1997 tests at the University of North Texas showed was that, at least in lab animals, mirror-image pseudoephedrine was equally as effective as regular pseudoephedrine as a decongestant. Unlike regular pseudo, however, the mirror-image version didn’t cause any side effects to the central nervous system, such as high blood pressure and a racing heart: the common “buzz” that one associates with cold medicine. Better yet for Warner-Lambert, mirror-image pseudoephedrine could only be synthesized into mirror-image methamphetamine, which, according to the Oregonian , had no stimulant effects and could not then be made into regular meth.

Had Warner-Lambert been unable in the end to develop mirror-image pseudo—or to bring it to the market—it had yet another option that would have significantly helped Haislip and DEA. Also in 1997, chemists at Warner-Lambert had begun experimenting with additives that would make it impossible to extract pseudoephedrine from Sudafed. This combination would undermine the basic building block of Nazi cold meth production, which is to pour anhydrous ammonia onto crushed-up cold pills in order to extract the pills’ pseudo. On this project, researchers at Warner-Lambert had, according to the Oregonian , been working closely with DEA. Moreover, the additives were already FDA-approved. Therefore, any drug containing them would not be considered new and would avoid the costly testing period mandated by the FDA. At the very least, manufacturing cold pills with these additives might have reduced the ever-increasing legions of small-time cooks like Roland Jarvis in states like Iowa, which at the time was seeing small-meth-lab increases of 300 percent a year.

If the cold pills with additives or, particularly, the mirror-image pseudoephedrine had come to market, the effect may well have been enormous. Were the U.S. cold medicine market, the largest in the world, suddenly dependent on any new form of pseudoephedrine, it stands to reason that the nine factories that provide all the planet’s pseudo would have begun producing large amounts of the new meth-resistant drug. This in turn would have drastically reduced the amount of meth-ready chemicals available to the DTOs. Either drug could have effectively accomplished what Gene Haislip and DEA had five times been unable to achieve between 1984 and 1996.

Instead, by the time Pfizer bought Warner-Lambert in 2000, all research into a cold-medicine alternative ceased. Why should Pfizer worry about DEA when its predecessor had had such an easy time lobbying Congress? In 2002, meth lab numbers in Iowa topped one thousand for the first time, and were nearing two thousand in Missouri.

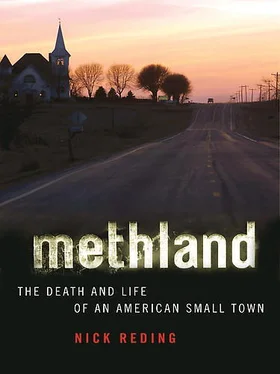

Oelwein’s difficult and unsure rebirth in 2006 began in the same place in which the town had been born 134 years earlier: in a cornfield. In 1872, Oelwein was founded on land belonging to Gustav Oelwein, a poor Bavarian farmer, as a place for what was then called the Rock Island Railroad to take on water and coal between Chicago and Minneapolis. The center point of town was plotted at the intersection of Charles and Frederick streets, so named for Gustav’s two sons. (Oelwein’s principal thoroughfare has three names—Charles, Frederick, and Old 150. Around town, all three are often referred to in the aggregate as “Main.”) By 1905, the population had soared to 5,134 people, and Charles and Frederick were among the wealthiest men in the Midwest. Driving south on Frederick Street today, you can still see the cabin where the Oelwein brothers were born. Heading farther south after a dogleg at the Country Cottage Café, what is now South Frederick dead-ends at Highway 150. To the left is an open parcel of land; to the right is a campground. Across Highway 150 is what might be the most important of all Oelwein’s undeveloped properties—the 250-acre Industrial Park. By the spring of 2006, the IP, as Mayor Larry Murphy calls it, was ready to be shopped to prospective customers and had unceremoniously been denuded of the corn that had grown there. Murphy foresaw the IP as the bright, shining future of his beleaguered town.

Unlike Gustav Oelwein, though, who’d already contracted with the three separate arms of the Rock Island Railroad (the Burlington, the Illinois Central, and the Minnesota), Larry Murphy did not know for whom he was preparing the IP’s land, which is bookended on one side by the two baseball diamonds of the grandiosely named Oelwein Sports Complex, and on the other by the once-famed Sportsmen’s Lounge. The idea was that, to reference one of Murphy’s favorite movies, Field of Dreams , if Oelwein cleared the land, somebody would come. The fact was that Oelwein had nothing to lose. And nowhere was this sentiment more clear than in the decrepit presence of the Sportsmen’s, whose mixed history underscores both the hope and the danger of a down-and-out place literally dying to grow bigger and stronger. It’s said around town that the Mob fronted the Pirillo brothers the money to open the Sportsmen’s, thereby adding to an already long and storied connection between the Cosa Nostra and the town that, in the 1950s, became known as Little Chicago.

Читать дальше