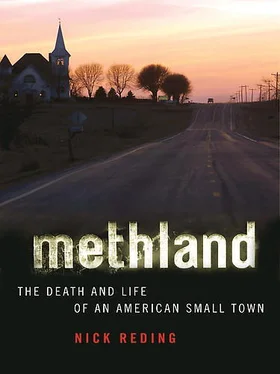

When Congress began debating the Combat Meth Act, it was without a trace of bipartisan rancor. Indiana Republican congressmen Mark Souder stood next to California Democratic senator Dianne Feinstein as they declared their moral obligation to take on meth and win. This seemed to be a macrocosm of what was happening in Oelwein, where Mayor Larry Murphy and the heretofore divided townspeople began to put aside their differences and rebuild. The message was that what was bad for the towns was bad for Washington, D.C., too; when it came to meth, everyone was working for the same thing. On a clear day, flying from New York to Los Angeles, or from Chicago to San Francisco, you might have looked at the small communities beneath the airplane in a different way, understanding better what they were up against, and in that way, you might have understood something of their vanishing place in the nation.

And then, just as suddenly as it started, the meth epidemic—along with the chance to understand what that epidemic really meant—was over. President George W. Bush’s National Drug Control Policy director, or so-called drug czar, John Walters, announced in August 2006 that “the war on meth,” for all intents and purposes, had been won. Shortly thereafter, the same newspapers that had briefly made the drug a cause célèbre began questioning whether meth had ever been an epidemic or just the creation of an overzealous media hungry for a good story. The popular media’s brief but intense exploration of meth in rural America, highlighted by several documentaries on both cable and network television, also ended. As the drug went back to being a regional bogeyman, the rural United States went with it, taking its place once again in anonymity.

What remained, however, was a town (and a nation) with a drug problem. The need to keep looking remained as well. In meth’s meteoric rise into the national consciousness and its subsequent fall, there were many clues to its deeper meaning in American culture. The fault lines, whether or not they made headlines, still overlaid the national topography just as completely as before. And maybe more so. What continued to take shape for me was the portrait of a town that stood as a metaphor for all of rural America and its problems. That’s to say that the evolution of the meth epidemic had occurred in lockstep with the three separate economic trends that had contributed to the dissolution of small-town United States. By looking closely at the events of 2006, one can see the parallel trajectories of meth and small-town economics—the one rising, the other falling—dating back to the days of the Amezcuas. And the things that spurred this simultaneous rise and fall: the development of Big Pharmaceuticals, Big Agriculture, and the modern Mexican drug-trafficking business. To look closely at the history of meth from 1990 to 2006 is to see more clearly than ever what Nathan, Clay, Murphy, Jarvis, and Lori Arnold have always been, and continue to be, confronted by.

It’s important to understand how a government that had for upward of a decade completely ignored meth’s spread from the West Coast into the Midwest and the Gulf States suddenly became alarmed. And how, just as suddenly, newspapers with only sporadic interest in reporting on the drug became obsessed with it. In some ways, the driving force behind each was the same: Steve Suo’s work at the Oregonian . Suo had written his first crank story back in 2003 when, in researching Oregon’s foster care system, he came upon a statistic that startled him: Eight in ten children under the state’s care admitted that their parents used meth. It’s in that way that Suo’s interest in the story changed. At first his question was, “Why is there so much meth in Oregon?” Eventually Suo turned his attention to how the drug had gotten to Oregon. Answering that question led him to Washington, D.C., where he uncovered the causal connection between meth, the pharmaceutical industry, and the U.S. government. By the time Suo left the meth beat at the end of 2006, he’d written, along with other reporters, a combined 261 articles for the Oregonian in less than two years.

What Suo’s reporting revealed was a timeline of failure, most of it at the crushing and unfair expense of Gene Haislip, DEA’s deputy assistant administrator in the Office of Compliance and Regulatory Affairs from 1982 to 1996. Up until 1987, Haislip had worked against the lobbyist Allan Rexinger, who represented the pharmaceutical company Warner-Lambert, to pass a bill that would monitor shipments of ephedrine powder entering the United States. Companies like Warner-Lambert, which used the ephedrine to make nasal decongestants, resisted the idea, fearing that it would lead to more stringent oversight. Rexinger, by appealing directly to the Reagan White House, had won the battle with DEA, forcing Haislip into a compromise that allowed bulk loads of ephedrine to enter the U.S. unmonitored, so long as the ephedrine was in pill—not powder—form.

The production of methamphetamine at the time was just industrializing, largely at the hands of the Amezcua brothers, who’d understood the lucrative, illegal application of the lax laws governing ephedrine imports. Once Haislip’s watered-down law passed, the Amezcuas simply bought ephedrine pills from legitimate sources, crushed them into powder, and used the powder to make meth. In addition, they began importing ephedrine powder into the port at Mazatlán, on Mexico’s Pacific coast, then driving the powder north across the border. As trade increased between Mexico and the United States, culminating in 1993 with the ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), truck traffic at ports of entry like San Ysidro, California, increased 278 percent, according to a study by UC-San Diego economics professor Joan Anderson. As a result, border security became more difficult to enforce, making it easier than ever to drive loads of ephedrine right into Los Angeles and the Inland Empire. Months after Haislip’s weakened bill passed, according to Suo, meth purity was at an all-time high throughout the West, indicating a glut in product. The spread of large amounts of the Amezcuas’ meth into Iowa and several other Midwestern states—thanks in great part to Lori Arnold of Ottumwa and to lesser extent to Jeffrey William Hayes of Oelwein—is one of what is sure to be many unreported side effects of this first, defining breakdown.

Haislip, though, was not done trying. By 1993, he was moving to close the loophole that his earlier bill had created, writing new legislation to limit imports not only of ephedrine powder but of pills, too. The law passed and seemed to produce immediate dividends: DEA, according to Suo, intercepted 170 metric tons of illegal ephedrine pills in eighteen months, reducing by a large chunk the available methamphetamine in the United States. In addition, Haislip took the unprecedented step of approaching the International Narcotics Control Board in Vienna, asking it to help DEA broker a deal with the nine factories in Germany, India, China, and the Czech Republic that produced the ephedrine. All the companies agreed. Using bills of lading to trace bulk loads of both raw ephedrine powder and finished pills that had been sent from their plants through third-party nations to Mexico, DEA was able to limit the number of countries through which ephedrine would travel to only those nations willing to keep serious records—all without significantly cutting into the profit margins of pharmaceutical companies. In just twelve months, according to Haislip, DEA blocked or seized 200 tons of ephedrine, or one sixth of the world’s annual production at that point, all of it earmarked for meth labs. Haislip’s sixteen-year-old plan of crippling the drug’s production by implementing multinational precursor controls seemed to be bearing fruit: across California, meth purity was down to an average of only 40 percent, an indication that production was slowing to a crawl.

Читать дальше