The Chilean translator, whose name is Jorge and who goes by George, is at once the party’s most curious guest and its most affable curiosity. He left Santiago de Chile when General Augusto Pinochet took over the country from Dr. Salvador Allende, the socialist pediatrician who’d been elected president in 1970; had given over the vast holdings of Chile’s elite to the underclasses; and had been killed three years later (while barricaded in his office at the Chilean White House) at the hand of Pinochet’s coup. In a sea of Levi’s, Dockers, and short-sleeved polo shirts, George stands out in his Wranglers, denim shirt, and shiny black cowboy boots. His wire-rim glasses and instinctive command of Marxist economics brand him a left-wing, idealist intellectual of a certain era in Latin American history, one heretofore unknown in Fayette County. The nephew of Salvador Allende’s secretary of education, George (by far) defines the furthest edge of the gathering’s largely centrist political agenda, which hinges on keeping taxes moderate and crop prices high; putting more money in the public education system; and keeping God in your life, but out of the government. By his mere presence, George also embodies the party’s, and the town’s, intuitively inclusionist sensibility.

Nonetheless, most people think George is Mexican. In a place where everyone has a grandfather whose native language was Norwegian or German or Italian, George represents the latest in the history of American immigration, complete with its unexpected quirks and hard-to-understand accents.

George, once he’d been exiled by Pinochet under the threat of death, had somehow ended up in Minneapolis, Minnesota. From there, a marriage took him to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, by way of Memphis, Tennessee. Divorced now, he spends his weekends playing music in local jazz ensembles. By day, he registers workers’ injuries to management at the windowpane factory on behalf of the mostly Mexican and mostly illegal labor force, a job he likens to selling Bibles in Kabul. Tammy Hallberg allows how all of that is “pretty darned interesting.” What she wants to know, though, is why more Mexicans can’t learn English. Even the Amish, she says, can do that.

Clay, seeing an opening, offers his explanation in terms of Hegelian dialectic and Whorfian hypothesis. Basically it amounts to this: If you’re not allowed to integrate into society (i.e., if you move from abusive job to abusive job, with no standardized manner of tracking your movements), then your choice of language will reflect this. It is a response with which George agrees so vehemently that only his native language can provide the right word to express his enthusiasm.

“Claro,” says George, nodding. “Claro.”

Tammy, too, relies on her native skills of communication, which are hammer-blunt. “Clay,” she says, “stop talking—right now.” And Dr. Clay does.

The food, excluding the hog, is potluck. When the UPS man is done carving the pork and heaping it on platters, he takes the platters to the kitchen. Tammy goes to the deck above the yard and rings a brass dinner bell. Surrounding the platters of pork are every manner of dish and container—Tupperware and Ziploc and microwaveable glass. What the containers lack in continuity, the foods make up for in their consistent use of corn as an ingredient and an equally consistent use of the loosest definition regarding the word “salad.” There is corn on the cob and corn that has been boiled and then shaved from the cob and mixed with butter and salt; corn bread with jalapeños; and roasted corn tossed with onions and chives. There is Idaho Red potato salad, and next to that, an enormous bowl of the same dish, this one made with baby Yukon Golds. There’s Jell-O salad, and bean salad, and a pot of boiled collard greens. For dessert, there is more Jell-O, this time molded like a wheel and resting on a seashell-shaped dish, and slices of warm, thick-crusted rhubarb pie with homemade vanilla ice cream.

When it’s all gone, except for the unending mounds of pork, the women stay inside, smoking in the kitchen or helping with dishes while Tammy divvies up twenty or so pounds of leftover hog meat into large bags, to be handed out to the guests when they leave, like door prizes. Meanwhile, the men retire to the yard. There, the drinking, in the finest Lutheran tradition, becomes steady and workmanlike as they sit in their chairs and smoke cigarettes and tell jokes, their voices hushed in the still night.

George the Chilean sits next to Charlie and listens while Clay tells the one about Earl and Maynard down at the VFW.

“Maynard,” begins Clay in his smoke-scarred voice, “is drunk as usual, sitting on his stool at the bar with Earl. And the next thing you know, Maynard pukes on himself.”

“I love this one,” says Charlie, leaning back in his camp chair. “This is a good one.”

“So Maynard says to Earl, ‘My wife just bought me this shirt. She’ll kill me.’

“Earl says, ‘Don’t worry. Just tell her I did it.’

“Earl reaches in his wallet, takes out a twenty, and puts it in Maynard’s chest pocket. ‘Tell her,’ he says, ‘that I gave you twenty dollars for a new shirt.’”

Clay reaches out his hand and acts out the exchange by pretending to put something in the breast pocket of George’s cowboy shirt.

“So,” Clay continues, “Maynard goes home, and his wife gives him hell. ‘But, honey, Earl did it!’ says Maynard. ‘And he gave me twenty dollars for a new shirt.’

“Maynard reaches in the pocket, pulls out the money, and hands it to his wife.

“She says, ‘There’s forty dollars here.’

“‘Right,’ says Maynard. ‘That’s because Earl pooped in my pants, too.’”

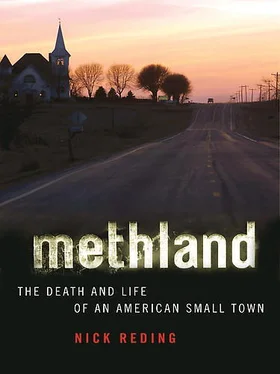

During 2006, meth, combined with America’s complicated reaction to it, began to accomplish what sociologist Craig Reinarman had said is the central function of drug epidemic: to “trace a culture’s sociological fault lines.” This happened in several ways. First, the American media made meth a cause célèbre. Second, state legislatures, tired of being ignored, began passing their own meth laws. This, in turn, drove the federal government to react to a drug it had ignored since Gene Haislip’s first failed campaign against meth at DEA, back when the Amezcua brothers were turning the drug into a blockbuster industry. Between the newspapers—mostly the Oregonian , in Portland—and the anger directed against Congress by state legislatures, a history of the federal government’s complicity in the meth trade was unearthed. What came into view is that pharmaceutical industry lobbyists had blocked every single anti-meth bill in the last thirty years with the help of key senators and members of Congress. Moved by so much bad press to do something immediately, Congress passed its first ever blockbuster meth law, the Combat Methamphetamine Act, in September 2006.

In some ways it was as though the United States was looking in a mirror, seeing itself in the rural towns to which methamphetamine had drawn the nation’s and the government’s gaze. Ironically, meth made Olwein’s connection with the rest of the country stronger and more visible than it had been for a long time. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Washington, D.C., where the drug’s effect on small-town America was now a salient political issue. The effect, as it registered in the public pages of national newspapers, was the kind of broad-scale unity that had never before existed, given that the drug had for ten years been regarded as a regional, not a national, phenomenon. Suddenly people in New York City knew what—if not exactly where—I was talking about when I mentioned meth in Oelwein, Iowa. The New York Times , the Boston Globe , the Washington Post , and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution joined the St. Louis Post-Dispatch , the Des Moines Register , the Fort Worth Star-Telegram , and the Los Angeles Times in running stories about crank almost daily. The nation seemed to feel a shared and equal sense of outrage, whether over meth-induced increases in HIV among San Francisco’s and New York’s gay populations, or the apocalyptic violence that resulted from shifts in the meth market along the Texas-Mexican border. The message was that civilized society was falling apart, that people were going crazy, and that the proof was no longer just in the hinterlands; it was everywhere.

Читать дальше