*CF. Die Zeit , MARCH 7, 1997. [FOOTNOTE BY WGS.]

J’AURAIS VOULU QUE CE LAC EÛT ÉTÉ L’OCÉAN — On the occasion of a visit to the Île Saint-Pierre

At the end of September 1965, having moved to the French-speaking part of Switzerland to continue my studies, a few days before the beginning of the semester I took a trip to the nearby Seeland, where, starting from Ins, I climbed up the so-called Schattenrain. It was a hazy sort of day, and I remember how, on reaching the edge of the small wood covering the slope, I paused to look back down at the path I had come by, at the plain stretching away to the north crisscrossed by the straight lines of canals, with the hills shrouded in mist beyond; and how, when I emerged once more into the fields above the village of Lüscherz, I saw spread out below me the Lac de Bienne, and sat there for an hour or more lost in thought at the sight, resolving that at the earliest opportunity I would cross over to the island in the lake, which, on that autumn day, was flooded with a trembling pale light. As so often happens in life, however, it took another thirty-one years before this plan could be realized and I was finally able, in the early summer of 1996, in the company of an exceedingly obliging host who lived high above the steep shores of the lake and who habitually wore a kind of captain’s cap, smoked Indian bidis , and seldom spoke, to make the journey across the lake from the city of Bienne to the island of Saint-Pierre, formed during the last ice age by the retreating Rhône glacier into the shape of a whale’s back — or so it is generally said. The ship which took us along the edge of the Jura massif where it plunges steeply into the lake was called the Ville de Fribourg . Among the other passengers on board were the gaudily attired members of a male-voice choir, who several times during the short crossing struck up from the stern a chorus of “Là-haut sur la montagne, Les jours s’en vont” or another such Swiss refrain, with the sole intention, or so it seemed to me, of reminding me, with the curiously strained, guttural notes their ensemble produced, of how far I had come meanwhile from my place of origin.

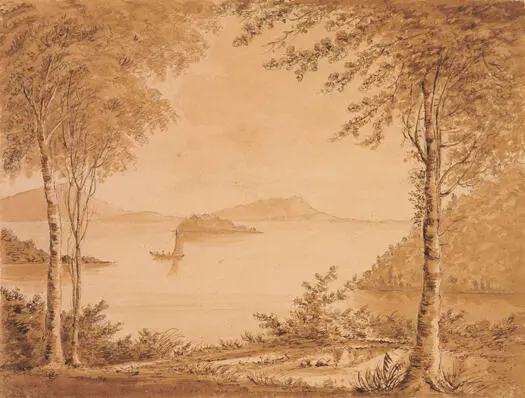

Apart from a single farmstead, there is now only one dwelling on the Île Saint-Pierre — an island with a circumference of some two miles — and that is a former Cluniac monastery which now houses a hotel and restaurant run by Blausee AG. After walking there from the landing stage, I sat for a while drinking coffee with my companion in the shady trellised courtyard, until it was time for him to take his leave and I watched from the gate as he made his way slowly down the white path, just like a sailor who, I thought to myself, after years of sailing the high seas finds himself washed up on the unfamiliar mainland once more. The room I took at the hotel looked out on the south side of the building, directly adjacent to the two rooms which Jean-Jacques Rousseau occupied when, in September 1765, exactly two hundred years before my first sight of the island from the top of the Schattenrain, he found refuge here, at least until the Berne Petit Conseil drove him out from even this last outpost of his native land. “By Saturday next,” as an edict sent to the Bailli in Nidau stated, “the said M. Rousseau is to remove himself from your Excellencies’ territories and shall not be permitted to return save under pain of the severest penalty.” In the decades after Rousseau’s death, when his fame had spread throughout Europe and beyond, an endless procession of illustrious personages visited the island to see for themselves the place in which the philosopher, novelist, autobiographer, and inventor of the bourgeois cult of romantic sensibility was for a brief period — as he claims in the fifth Promenade in the Reveries of the Solitary Walker —happier than in any other place. The adventurer and confidence trickster Cagliostro, the French conseiller du Parlement Desjobert, the English statesman Thomas Pitt, diverse kings of Prussia, Sweden, and Bavaria, all came to the island, not least among them the former Empress Joséphine. Early in the morning of the thirtieth of September 1810, hours before the arrival of the most beautiful woman of her day, a crowd a thousand strong was already waiting by the shore, and on the lake itself the ships and boats garlanded with flowers and flags thronged together in such numbers that the water could scarcely be seen. And when, twenty years later, the Poles arrived in Switzerland after the violent suppression of their uprising, the island on more than one occasion served as a meeting place where the refugees — for many a source of admiration — and the liberals who sympathized with their cause organized ceremonies to commemorate those who had fallen in the fight for freedom. On one such occasion in 1833, as Werner Henzi recalls in his prospectus of the Rousseau island, an enthusiastic crowd surrounded an altar set up between two chestnut trees, covered in black cloth, on which the book of the Rights of Man lay shrouded in black crêpe while the nearby trees were decorated with the Lithuanian coat of arms and the White Eagle, emblem of the ancient Polish nation. Throughout the nineteenth century, too, other, private individuals included Rousseau’s island on their itineraries, sensitive and cultivated readers such as, for example, the young Englishwoman Caroline Stanley, who visited the Lac de Bienne in the summer of 1820 and painted this view of the Île Saint-Pierre — along with the Grindelwald glacier and other wonders of the Swiss landscape — in her watercolor album, which I came across recently in an antiquarian bookshop in Zurich.

A number of these visitors, too, carved their initials or the date of their visits with a penknife in the doorjambs and window seat of the Rousseau room, and as one runs a finger along these grooves in the wood, one wishes one could know who they were and what has become of them.

In the course of our own century, now nearing its end, this Rousseau mania has gradually abated. At any rate, in the few days I spent on the island — during which time I passed not a few hours sitting by the window in the Rousseau room — among the tourists who come over to the island on a day trip for a stroll or a bite to eat, only two strayed into this room with its sparse furnishings — a settee, a bed, a table, and a chair — and even those two, evidently disappointed at how little there was to see, soon left again. Not one of them bent down to look at the glass display case to try to decipher Rousseau’s handwriting, nor noticed the way that the bleached deal floorboards, almost two feet wide, are so worn down in the middle of the room as to form a shallow depression, nor that in places the knots in the wood protrude by almost an inch. No one ran a hand over the stone basin worn smooth by age in the antechamber, or noticed the smell of soot which still lingers in the fireplace, or paused to look out of the window with its view across the orchard and a meadow to the island’s southern shore. For me, though, as I sat in Rousseau’s room, it was as if I had been transported back to an earlier age, an illusion I could indulge in all the more readily inasmuch as the island still retained that same quality of silence, undisturbed by even the most distant sound of a motor vehicle, as was still to be found everywhere in the world a century or two ago. Toward evening, especially, when the day-trippers had returned home, the island was immersed in a stillness such as is scarcely now to be found anywhere in the orbit of our civilized world, and where nothing moved, save perhaps the leaves of the mighty poplars in the breezes which sometimes stirred along the edge of the lake. The paths strewn with a fine limestone gravel grew ever brighter as I walked along them in the gathering dusk, past fenced-in meadows, past a pale motionless field of oats, a vineyard, and a vintner’s hut, up to the terrace at the edge of the beech wood already black with night, from where I watched the lights go on one after another on the opposite shore. The darkness seemed to rise out of the lake, and for a moment as I stood there gazing down into it, an image arose in my mind which somewhat resembled a color plate in an old natural history book and which — though more precise and more attractive by far than any such colored print — revealed numerous fish of the lake as they hung sleeping in the deep currents between the dark walls of water, above and behind each other, larger and smaller ones, roach and rudd, bleaks and barbels, char and trout, dace and minnows, catfish, zander and pike and tench and graylings and crucian carp.

Читать дальше