Winfried Sebald - A Place in the Country

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Winfried Sebald - A Place in the Country» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Hamish Hamilton, Жанр: Публицистика, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Place in the Country

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hamish Hamilton

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Place in the Country: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Place in the Country»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, he reflects on six of the figures who shaped him as a person and as a writer, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Robert Walser and Jan Peter Tripp.

Fusing biography and essay, and finding, as ever, inspiration in place — as when he journeys to the Ile St. Pierre, the tiny, lonely Swiss island where Jean-Jacques Rousseau found solace and inspiration — Sebald lovingly brings his subjects to life in his distinctive, inimitable voice.

A Place in the Country

A Place in the Country — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Place in the Country», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

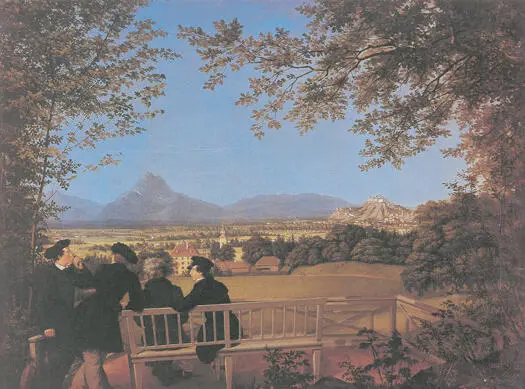

The calm of the domestic interior and the projection of an image of peaceable domesticity onto the surrounding landscape is one of the recurring motifs of Biedermeier painting. A sparsely furnished study, pale green walls, scrubbed floors of bleached pine, children playing table skittles, a parrot or parakeet in a cage, a young woman at the window, a sailing ship outside in the harbor, or in the far distance, beyond fields and hedgerows, the foothills of the Vienna Woods — Nature domesticated. The view of Salzburg painted by Julius Schoppe in 1817 shows a small group of men gathered on a bench in the foreground — the artist and his comrades, like Lohbauer’s Tübingen friends, recognizable by their apparel as sympathizers of the progressive national cause. Yet what could possibly be improved upon in this perfectly ordered prospect? Framed by greenery, overarched by a radiant blue sky, it is the very image of perfection.

A light veil of shadow lies across a field smooth as an English lawn below the terrace on which they are gathered to admire the view, and two tiny figures are walking along the path leading to Schloss Aigen, with the plains beyond gleaming in the sunlight; neatly clipped round trees line a long avenue, and beneath the castle the towers and houses of the city, surrounded by the wide blue arc of the mountains, shimmer in the sun. Exactly so, in Mörike’s work Das Stuttgarter Hutzelmännlein [The Cobbler-Goblin of Stuttgart], the Schwäbische Alb appears, seen from the Bempflinger Höhe, as the wondrous glass-blue wall beyond which “as he was told as a child, lie the cockleshell gardens of the Queen of Sheba.” If we gaze into this safely bounded orbis pictus for long enough, we can easily imagine that here someone has stopped the clock and said: this is how it should be forever after. The ideal world of the Biedermeier imagination is like a perfect world in miniature, a still life preserved under a glass dome. Everything in it seems to be holding its breath. If we turn it upside down, it begins to snow a little. Then all at once it becomes spring and summer again. It is impossible to imagine a more perfect order. And yet on either side of this apparently eternal calm there lurks the fear of the chaos of time spinning ever more rapidly out of control. When the young Mörike begins writing, he has at his back the revolutionary upheavals of the end of the eighteenth century, while the terrors which herald the new age of industrialization are already silhouetted on the horizon, the turmoil unleashed by the accumulation of capital and the moves toward centralization of a new, cast-iron state authority. The Swabian quietism Mörike subscribed to is — like all the Biedermeier arts — a kind of instinctive defense mechanism in the face of the calamity to come. In actual fact the everyday life of the time was far less secure than today’s envious observer might imagine. Everywhere in the work of Grillparzer, Lenau, and Stifter, dark abysses open up in their tales of family life: fear of bankruptcy, ruin, disgrace, and déclassement . There are children who drown themselves in the Danube, brothers in prison or in the asylum, suicide and syphilis. Mörike, never far from the brink of financial ruin after he resigned his living as a vicar, knew from at least the age of thirteen — when his father died following a stroke — how precarious life in bourgeois society could be. His hypochondria, the mood swings he was constantly prone to, his feelings of faintheartedness, and the weariness of which he so often speaks; unspecified depressions, symptoms of paralysis, sudden weakness, vertigo, headaches, the terrors of uncertainty which he continually experiences — all these are symptoms not only of his melancholic disposition, but also the spiritual effects of a society increasingly determined by a work ethic and the spirit of competition. Things are sometimes so bad that he goes around “like a frightened chicken” or “a stupid child who cries at everything.” In his request to be released from his duties addressed to King Wilhelm I in 1843, he describes how at his last christening — after he had already had to call upon the assistance of a neighboring cleric during the morning sermon — he suddenly felt so unwell that “the congregation as well as I myself expected me to fall unconscious.” Mörike’s fainting fits, and the impotence they express, are not least responses to the increasing consolidation of power in Germany, in the face of which he finds it ever more difficult to maintain his position in office, let alone hold his own as a poet in the new nation. Throughout his life he progressively retreats further and further from the exertions of artistic production, occupying himself with the revision of his novel, translating, busying himself with the composition of humorous poems and a long tail of occasional verses — engraved on a plant pot from Lorch for Wolff’s wife; with the famous Schöntal recipe for pickled cucumbers for Constanze Hartlaub; on the occasion of the dedication of the Stuttgart Liederhalle, and suchlike — and he doubtless often fears amid all this that he has lost sight of the true thread of his writing, and that quite possibly he will soon be sitting up in bed, like his father after the stroke, with his pen in his trembling hand, searching for the right expression and completely incapable of finding it.

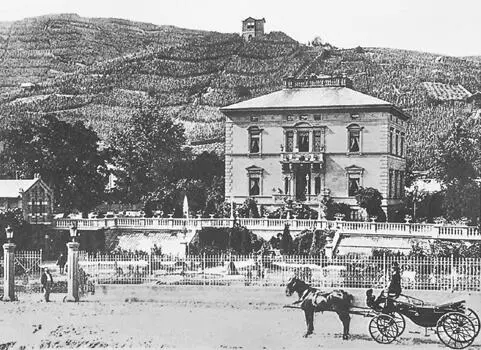

Plagued by inner anxieties and constrained economically — as he had been from the outset, and continued to be during his more than three decades as a retired minister — apart from two trips to Lake Constance and an excursion across the border into Bavaria, Mörike never, so far as I am aware, ventured beyond the narrow confines of his native Württemberg. Ludwigsburg, Urach, Tübingen, Pflummern, Plattenhardt, Ochsenwang, Cleversulzbach, Schwäbisch Hall, Nürtingen, Stuttgart, and Fellbach — these were his staging posts in an age otherwise in the grip of railway mania, stock market speculation, risky credit deals, and general expansionism. The peaceful backwater of the Biedermeier age resembled a wishful utopia erected against progress, a painted screen disguising a world radically changing from the very foundations and opening up to new influences on all sides. Only once, as a young man, did Mörike venture beyond the limits of the Kingdom of Württemberg, when he composed his South Sea fantasy — perfect for opera — of the land of Orplid. The inspiration for this draws less on the idea, by then almost forgotten, of the Noble Savage than it anticipates the era which Mörike almost lived to see, in which, in the new imperial capital of Berlin, allotment settlements are created with names like Frohe Eintracht [Cheerful Harmony], Ostelbien [East of Elbe], Alpenland [Alpine Lands], and Burenfarm [Boer Farm], names that owe their origins not only to the expansion of the Vaterland from the Adige to the Belt, but also to the colonialist aspirations to a German Africa and a German Tahiti. While Mörike was busy writing in Cleversulzbach or Schwäbisch Hall, the scale and proportions of the world were shifting in unpredictable ways. The Texan Consul

had a villa built for himself among the Stuttgart vineyards, and the Kingdom of Württemberg became an anachronism; it became necessary to think on a grand scale, and work en miniature was abandoned in favor of a monumentalism enacted ever more recklessly from decade to decade. Nor was Mörike’s own writing unaffected by this development. His novel Maler Nolten [ Nolten the Painter ] is an experiment on a grand scale, in which over the course of several hundred pages an extraordinarily complex plot is unfolded. The young artist Theobald Nolten, as Birgit Mayer writes in her introductory book on Mörike, “makes the acquaintance, via his former servant Wispel, of the newly successful artist Tillsen and sees his career advanced by the latter. Through Tillsen, Nolten is introduced to the society of Count Zerlin, and, believing himself deceived by the — alleged — infidelity of his fiancée, Agnes, falls in love with the Count’s sister, Constanze. From this point on, fate takes its course. His relationship with Agnes had been on the one hand undermined by an intrigue on the part of the gypsy girl Elisabeth, yet on the other sustained — or so it appears — by a counterintrigue in Nolten’s name by his friend, the actor Larkens. The negative climax of the novel is reached when Constanze breaks with Nolten after finding out how things really stand. Verse interludes, a magic lantern show, and idyllic interpolations form a precarious counterbalance to the looming threat but cannot avert it. In the further course of the action all the characters become ever more deeply enmeshed in secretive and tragic mutual dependencies, which in the end none of them survives.” From this deliberately abbreviated summary, which can scarcely begin to do justice to the emotional and social complexities involved, one may deduce that Mörike was beginning to lose his way in this ambitious undertaking, freighted as it was with subsidiary characters and episodes, interludes and subplots, and all manner of digressions and diversions. If his myopic eyes are often able to detect hidden wonders in the smallest detail, his eye grows dim if it falls on a wider panorama, and the twists and turns of fate which he invents for his characters soon dissolve into melodrama: “The clock was just striking eleven. In the Zerlin household all had grown still, only in the bedroom of the Countess do we still find the lights burning. Constanze, in her white nightclothes, sitting alone at a small table near her bed, is busy letting down her beautiful hair, taking off her earrings and her delicate string of pearls, which always adorned her neck with such simple charm. Lost in thought, she held the necklace on her little finger up to the light, and if we rightly read her brow, it is Theobald of whom she is thinking.… Restlessly she arose, restlessly she stepped to the window and let the magnificently bright heavens with all their portent, with all their splendor, act upon her. Her love for that man, from its first imperceptible stirrings to the astonishing state of her full awareness of it, from that moment in which her feelings had already become yearning and even desire to the pinnacle of the most powerful passion — that whole range she now traversed in her mind and found it all beyond comprehension.” Immediately after this somewhat dubious passage we learn of Nolten’s “irresistible ardor,” of the “full sweet ferment” of love which “enveloped the senses” of the Countess in her remembered scene in the grotto; of “the womb of an all-knowing fate,” of “ardent gratitude” and “most heartfelt pleas.” The inflamed passion of elective affinities Mörike may have had in mind has inadvertently evolved into something precariously close to a better class of sensationalist romance, and among the vistas of parks and gardens which he has erected on the narrative stage, our Swabian vicar — who unfortunately is by no means at home in this aristocratic milieu — wanders around rather gloomily and just as aimlessly as poor Schubert in Rosamunde or in Berté’s Dreimäderlhaus . Like those of Mörike, Schubert’s theatrical and operatic ambitions — which he hoped would lead to rapid success and at least a temporary relief from his financial dependence on his friends — often misfired, and, as on occasion in Mörike’s poetry, so, too, in Schubert’s works the most masterful strokes of genius are most readily to be found in the hidden shifts of his chamber music, for example the opening of the second movement of his last piano sonata, or in the song “Die liebe Farbe” from Die schöne Müllerin; in those true moments musicaux where the iridescent chromatics begin to shimmer into dissonance and an unexpected, even false change of key suddenly signals the abandoning of all hope, or, alternatively, grief gives way to consolation. Mainly it is the Moravian Dorfmusikanten [village musicians] whom one sees Schubert accompanying on their travels from village to village. He is more at home with them than he is toiling away at the high art which bourgeois notions of culture demand. Indeed, there is a portrait of Mörike in which he looks almost exactly

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Place in the Country»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Place in the Country» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Place in the Country» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.