Rêveries d’un promeneur solitaire , which he completes in April 1780. After that he leaves Paris and moves into a small house in the park at Ermenonville which the Marquis de Girardin has placed at his disposal. He lives there for five more weeks in early summer. He rises at dawn, goes for walks, leaning on his cane, in the beautiful surroundings,

collects leaves and flowers, and sometimes takes a boat out onto the lake. On the second of July — he is sixty-six years old — he comes back from one of his walks with a terrible headache. Thérèse helps him into a chair. Felled by a stroke, he collapses onto the floor and, after a few convulsions, dies. Two days later he is buried at Ermenonville on the Isle of Poplars. In the years that follow, the Marquis transforms his estate into a parc du souvenir . He has a classical monument erected, the Swiss chalet is completed, a Temple of

Philosophy is constructed with an altar dedicated to reverie. Even the cabin in front of which Rousseau would often sit on a bench, gazing out over the peaceful landscape, is carefully preserved. The park has become a site of pilgrimage, and more than one lady sinks down before the grave on the island, pressing her bosom against the cold stone beneath which Rousseau’s earthly remains rest, until, that is, on the ninth of October 1794 they are transferred to the Panthéon. On this memorable day, a group of musicians performed excerpts from the opera Le Devin du village; the oak coffin, triple-lined with lead and further clad with an outer lead covering, was raised from the earth and taken to Paris in a grand and solemn cortège. In all the villages along the route the people lined the streets calling “Vive la République! Vive la mémoire de Jean-Jacques Rousseau!” On the evening of the tenth of October the procession arrived at the Tuileries, where a huge crowd was waiting with flaming torches. The coffin, covered by a wooden framework painted

with the symbols of the Revolution, was placed on a bier surrounded by a semicircle of willows. The main part of the ceremony took place the following morning, when the funeral procession continued on its way to the Panthéon, led by a captain of the United States Navy bearing the banner of the stars and stripes and followed by two standard-bearers carrying the tricolore and the colors of the Republic of Geneva.

WHY I GRIEVE I DO NOT KNOW. A memento of Mörike

When Eduard Mörike arrived in Tübingen to begin his studies at the Stift in 1822, the times had already changed. The previous year, the Emperor who had turned the world upside down all over Europe had died rather a miserable death on a rocky outcrop in the desolate wastes of the South Atlantic, and his precursor, the trailblazer with the red Phrygian cap, had also long since vanished from the stage of history. Now the firebrand of the Revolution is only evoked to give a fright to little children. Through their startled eyes we see it flare up one last time outside the window, see it once more burst in at the gate, watch the flames rise from the roof beams and our house collapse in ruins. At the end of this terrible recollection, though, we learn that all that was a very long time ago, and the fire-raiser among us no longer:

Nach der Zeit ein Müller fand

Ein Gerippe samt der Mützen

Aufrecht an der Kellerwand

Auf der beinern Mähre sitzen

Feuerreiter, wie so kühle

Reitest du in deinem Grab!

Husch! Da fällts in Asche ab.

Ruhe wohl,

Ruhe wohl,

Drunten in der Mühle!

[Time passed — and a miller found

The rider’s skeleton, cap and all,

Leaning on the cellar wall

Still upon his bony mare.

Fire rider, oh, how coldly,

You ride to your grave, so boldly!

Whoosh, to ashes all does fall.

Rest in peace,

Rest in peace,

Below there in the mill!]

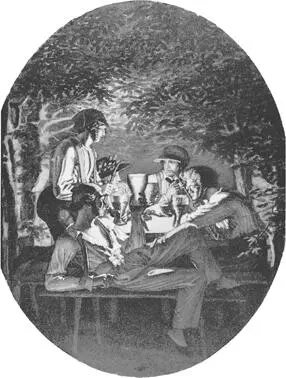

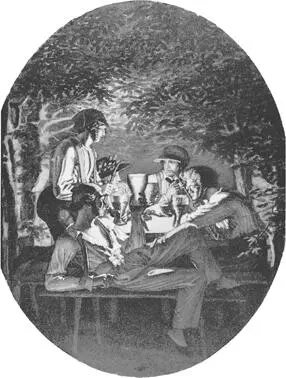

If, for the young Mörike, the terrors of the Revolution have already receded into a legendary and distant past, the closing acts of the Napoleonic era — the battles of Leipzig and Waterloo, which as a child he must have heard a great deal about — surely formed part of his own memories; and part of the dawning consciousness of his generation was shaped by the hopes for the sovereignty of the people which liberation from French rule was supposed to bring about. The “wild poet” Waiblinger, whom Mörike met in 1821 and whose writings for a long time continued to hold fast to the revolutionary ideal, is the most apt witness to this. Despite the heavy hand with which the states of the Holy Alliance had been governed for almost a decade, the dream of a national uprising was not yet dead. The clearly drawn lines of 1812 had, however, long since become blurred. Increasingly, visions of the future were becoming less and less clear-cut, and in the minds of the occupants of the Tübingen Stift , too, were becoming refracted into that ur-German blend of revolutionary patriotism and bourgeois circumspection, romantic imagination and double-entry bookkeeping, political zeal and poetical effusiveness, in which the progressive elements can scarcely any longer be distinguished from the reactionary. “On the one hand, there was great enthusiasm, with the likes of Byron, Waiblinger and Wilhelm Müller … for the Greek Wars of Independence against the Turks, and on the other hand a yearning for the contentment of peace, hearth and home,” writes Holthusen in his monograph on Mörike, in this context also recalling the well-known pen-and-ink drawing by Rudolf Lohbauer showing

the artist and his friends “drinking and smoking in a Tübingen summerhouse which he had furnished as a kind of buen retiro .” In this picture, which gives a clear idea of the way the atmosphere of those years oscillated between the impulses of political awakening and retreat from the world, we see, gathered together in the lamplight, five young men dressed in the kind of fanciful costume fashionable at the time as a gesture of rebellion against authority, part olde-worlde German, part modishly rakish: open-necked shirts with wide flowing sleeves, Renaissance berets and suchlike extravagant headgear, sideburns and unkempt locks and those strange small steel-rimmed spectacles which have clearly been the hallmark of the conspiratorial intelligentsia since time immemorial. It is not immediately apparent whether this subversive style, which was all the rage at the time, was actually an expression of militant liberalism or whether it was mere playacting and fancy dress, but one would not be far wrong in assuming that the revolutionary impulse of the Wars of Independence was, from 1820 onward, beginning to dissolve in a fug of tobacco smoke and Biergarten bravado. For almost the whole of the nineteenth century, indeed, one could say that the Stammtisch took the place of parliament in Germany. Perhaps this is why, at barely eighteen, Mörike already detects the false notes in the enthusiastic eulogies held by the would-be avant-garde in praise of Kotzebue’s murderer, Sand. Admittedly Mörike was, from the outset, even more inclined to resignation than most. In this he is a true representative of a generation which, still just touched by the breath of a heroic age, is preparing to enter upon the becalmed waters of the Biedermeier, in which bourgeois domesticity takes precedence over public life and the garden fence becomes the boundary of a life en famille which conceives of itself as a universe in its own right.

Читать дальше