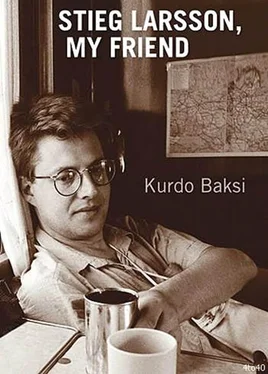

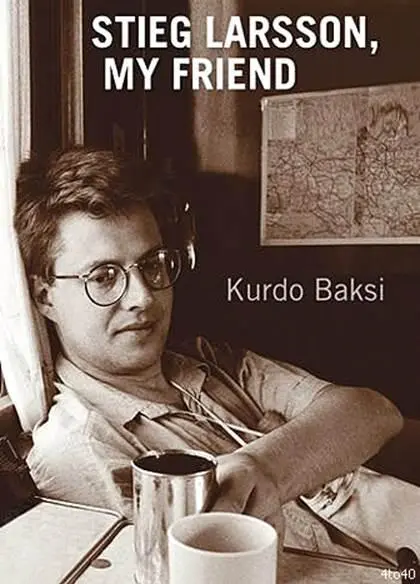

Kurdo Baksi

Stieg Larsson, My Friend

Simultaneously published in Sweden as Min vän Stieg Larsson by Norstedts, Stockholm, and in Great Britain as Stieg Larsson, My Friend by MacLehose Press, an imprint of Quercus, 21 Bloomsbury Square, London WC1A 2NS.

Copyright © Kurdo Baksi, 2010

English translation copyright © Laurie Thompson, 2010

The end and a beginning

Stieg Larsson’s funeral took place on Friday, 10 December, 2004, in the Chapel of the Holy Cross at Forest Cemetery in southern Stockholm. The chapel was packed with relatives, friends and acquaintances. We filed past the coffin to pay our respects. Most of us whispered a final message as we walked slowly past the bier.

On the back of the order of service was a poem by Raymond Carver, “Late Fragment”, from the collection he completed shortly before his death:

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

When Carver was asked how he wanted to be remembered, he replied, “I can think of nothing better than to have been called an author.” Not many of the congregation in the chapel that afternoon would have realized that the same applied to Stieg. That he would be remembered as the author of one of the biggest, least expected publishing successes of modern times. For most of us he was a tireless hero in the fight against racism – there was no battle for democracy and equality that he was unwilling to take part in. He was aware that there was a high price attached to doing so, but it was a price he was prepared to pay. The constant threats, the lack of financial resources and the sleepless nights. It was a struggle that shaped his whole life.

But Stieg became an author – thanks to the capriciousness of life and death – only when he was no longer with us.

That afternoon we attended an uplifting memorial ceremony at the Workers’ Educational Association in Stockholm, a venue at which Stieg had been keen to lecture ever since the publication of his first book, Extremhögern (The Extreme Right), in the spring of 1991. Tributes came thick and fast, delivered by, among others, his father, Erland Larsson, his brother, Joakim Larsson, his partner, Eva Gabrielsson, the publisher of Expo magazine, Robert Aschberg, the publisher-in-chief at Norstedts, Svante Weyler, the historian Heléne Lööw, Graeme Atkinson from the British magazine Searchlight and Göran Eriksson, the head of the Swedish W.E.A. I was master of ceremonies.

After the memorial ceremony we repaired to Södra Teatern, the theatre in the Söder district of southern Stockholm, a favourite haunt of Stieg’s in his last years, for a funeral feast. It was icy cold on the terrace; the December chill froze us through and through. We shared our grief – family, friends, acquaintances and the entire staff of Expo . It was late at night before we broke up. We trudged home, each of us with our own memories of Stieg etched indelibly on our minds.

That was when the really difficult part began. Mourning in private.

“Farewell” is a hard word to define. Who is saying farewell to whom? The one who leaves or the one who stays behind? I keep coming back to that question over and over again. Of course I have lost a lot of friends and acquaintances over the years, but Stieg was my first really close friend to die. I set myself very high standards while grieving, but found myself groping around helplessly even so. I didn’t know how to mourn with sufficient intensity.

After a while I realized that my memory was failing me. I forgot the names of people, lost my sense of direction, became anxious and depressed. But all the while the same message was pounding away at the back of my mind: I had to be strong. Stieg’s partner, Eva, and the young members of the Expo staff needed me. I couldn’t let them down now. I must not burst into tears in front of friends and acquaintances. I had learned a lesson from my time in the mountains of Kurdistan during the freedom struggle there: there is a time to weep, and a time to maintain a stiff upper lip and do whatever needs to be done.

I realized that I had to compromise. For a long time I avoided Expo and the places where Stieg and I used to meet: Il Caffè, Café Anna, Café Latte, the Indian restaurants on Kungsholmen and McDonald’s in St Eriksgatan. Eventually I began to behave in exactly the opposite way. I wore black and made a point of going to the places I used to frequent with Stieg. It wasn’t that I imagined we were sitting there together. It was rather a case of going there in order to come to terms with my own situation, irrespective of whether I actually wanted a meal.

Months passed. Eventually the day came when the first reviews of Män som hatar kvinnor (Men Who Hate Women, in English called The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo ) were published. I eagerly devoured every word and was overwhelmed by a strange feeling: I took everything that was said about the book personally. I began to regard myself as a sort of stand-in for Stieg. The reviews were almost exclusively positive, which pleased and distressed me at the same time. I was pleased by the thought that the books were going to be read by a lot of people, distressed because Stieg wouldn’t be able to experience this for himself.

Eventually the first anniversary of that awful day came round. Rain pelted remorselessly against the windowpanes during the night of 8 November. My flat was only a stone’s throw from Stieg’s house. I was overcome once more by a tidal wave of sorrow and longed to be able to talk to him. I wished I could tell him that I was in love with a woman I knew he had met at one of the parties we had attended together. But there was only silence. I sat there, staring at the black and white tie Stieg had worn the last day of his life, the one Eva had given me as a keepsake. He should be close by, I thought, but he felt so dreadfully far away.

Maybe that was the moment when it finally came home to me that he had left us for good. I would never see him again. That night I made up my mind to travel to Skelleftehamn, the town in northern Sweden where he had been born, and to Umeå, where he had grown up. I bought plane tickets and prepared for the journey, but when the departure day dawned I realized that there was no chance of my travelling. Perhaps I’d be able to cope later on, but not yet. In fact I turned down several assignments in places close to his home territory: I still wasn’t up to it.

Stieg’s success as a writer did more than continue; if anything, the second volume in the Millennium trilogy, Flickan som lekte med elden ( The Girl Who Played with Fire ), was even more of a triumph. People in the trade began to talk about the most successful Swedish books of all time – and the third volume, Luftslottet som sprängdes ( The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets’ Nest ), hadn’t even been published yet. Stieg’s name appeared in the newspapers almost every day; people on buses and in the underground had their heads buried in his books. He was still a constant presence in my life.

It struck me how little I actually knew about Stieg’s existence before we met. He hardly ever mentioned the first twenty years of his life during all the time we were good friends. I began to wonder if something had happened in his youth that made it difficult for him to be in the spotlight. He always refused to think of himself as important in any respect. On the other hand, he thought a lot of other people were important.

Читать дальше