Toole, John, 95

Traynel, le Marquis de, 239–40

United States military in France: American stereotyping of French social norms, 2, 263n3; authorities’ reaction to rape accusations, 10–11; commissaires ’ reports on Franco-Allied relations, 5–6, 264n11; French view of America as a wealthy nation ( see American GIs and French civilians); historians marginalizing sexual contact between GIs and women, 11; historical significance of sex to the US military presence in France, 260–61; impact of uncontrolled GI behavior on Franco-American relations, 76–77; impact on the French male ( see wartime male gender damage); influence of perception of French sexual attitudes on the military’s imperialistic view of France, 54–55; instances of good Franco-American relations, 106, 292n144; leaders’ efforts to manage the military’s image ( see GI photos; military’s view of prostitution; propaganda by the military); military propagandists leveraging myths about French women to motivate the GIs, 7–9; political issues facing France regarding US-Franco relations, 4–5; political meanings behind sexual relations, 7; price paid by the population for liberation, 27, 255–56, 268nn73–77; prostitution and ( see Parisian prostitutes; prostitution); rape prosecutions ( see military court system for rape trials; rape); situation for black soldiers ( see African American soldiers); spread of venereal disease, 10; theater of war ( see Battle of Normandy); “Times Square Kiss” symbolism, 258, 259f; unintended consequences of the myth of the manly GI, 9–10; US military’s condescending attitude toward postwar France, 2–4; US policy toward France’s leadership, 5–6, 263n7; US rise to power reflected in sexual exploitation of French women, 257; view that command of geographical territory signaled command of sexual territory, 87

USO shows, 44

Vanier, Jean, 132

Vautier, Jean-Jacques, 47

venereal disease (VD): army efforts to reduce exposure to, 166–67, 314n50; army’s failed initiatives to reduce instances of, 167–69, 314n56; basis of the soaring rates of infection, 167; concern over its impact on war readiness, 162–63; in Italy, 163–64; military’s view of black soldiers’ exposure to, 164–65, 312nn30–31; officers’ motivation to conceal cases, 172; prevalence among Parisian prostitutes, 135, 140; spread of, by the soldiers, 2, 10; symbolic connection between VD and Allied anxieties, 165–66

Vercors, 86, 132, 268n77, 284n6, 300n145

Virgili, Fabrice, 79, 87

Voisin, Pierre, 1, 74–75, 181–84, 239

WAC (Women’s Army Corps), 165–66

War, Beverly, 329n142

Wardlaw, Fred, 44

Wartime (Fussell), 264n20

wartime male gender damage: alleged German rapes used to create a moral imperative for war, 87, 285n12; American dismay at the FFI’s role in épuration of collaborators, 97; American power illustrated by GIs’ ability to command favors of women, 105–6, 292n140; Americans’ lack of respect for the French Army, 94–95; damage done to French male authority by the war, 110, 172n172; ex-prisoners’ marginalization upon return home, 107–10; FFI view of Americans and of their own manhood, 99–101; France’s dismay at its geopolitical decline, 90–92; French man’s shame and rage at not being able to fulfill his task as chef de famille , 86–87, 92, 284nn3–7; French men’s attempt to ignore the Americans’ attitude, 105, 292n137; French men’s response to American “rescue” of their country, 85; French peoples’ ignorance of the war due to poor news access, 89–90; frustration over repatriation progress, 106–7, 292n148; GI condescension of French men, 88–89, 92–95; GI discomfort with the tonte rituals, 97–98, 288n80; GI reviews of the Resistance, 95–97, 98–99, 287n58, 288n76; GIs’ belief that they deserved the sexual prerogatives of conquest, 108–9; GIs’ condescending attitude toward liberated detainees, 103–4; GIs’ need to assert their own manliness, 93–94; GIs’ view of French women as transferred property, 89; instances of good Franco-American relations, 106, 292n144; liberated French prisoners’ dismay at GI treatment of them, 101–3, 290n103, 290n108; problem of sexual tensions between French and American men, 108–10; Stars and Stripes ’ consistent denigration of French masculinity, 77, 81–83; tonte ritual’s symbolism, 87–88, 98, 108, 133; US Army’s reasons for not being friendly toward the liberated, 104–5; US view that command of geographical territory signaled command of sexual territory, 87; war’s impact on French global status related to, 90, 92, 286n29

Washington, Forrest, 222

Watson, James, 200

Weaver, William, 201

Weed, T. J., 1, 2, 75, 182, 318n141

Westfield, Fred, 210

Weston, Joe, 2, 75

White, John, 222

White, Walter, 199, 233, 234, 331n183

Whiting, Charles, 135, 146, 150

whorehouses ( abattoirs ), 140

Wicker, Paul, 104

Wiener, Frederick Bernays, 326n68

Wilkins, Roy, 199, 232

Williams, John, 333–34n2

Williams, L. C., 209, 210

Wilson, Florine, 207

Wilson, J. P., 210

Winston, Keith, 54, 121, 122

Women’s Army Corps (WAC), 165–66

Worton, Samuel D., 218

Yalta, 90

Yom, Sun, 313n31

Zig Zag phrase, 125, 153, 308n148

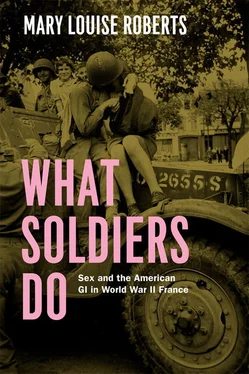

Mary Louise Robertsis professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the author of Disruptive Acts: The New Woman in Fin-de-Siècle France and Civilization without Sexes: Reconstructing Gender in Postwar France, 1917–1927 .

“In this vivid account of GIs in wartime France, Mary Lou Roberts documents how the Greatest Generation was sometimes as badly behaved beyond the battlefield as it was brave in combat. What Soldiers Do is not a conventional history. It deeply—and often colorfully—textures our understanding of the experiences of men at war, the contours of mid-twentieth-century sexual (and racial) mores, and the frequently ignorant and even lurid attitudes toward other peoples that attended America’s ascent to global hegemony.”

(David M. Kennedy, author of

Freedom from Fear )

“Mary Louise Roberts’s provocative counter-narrative of America’s ‘good war’ reveals the fraught entanglements of gender and race, sex, sexual violence and racism, commerce and romance, in the Franco-American encounter from D-day through the first year of uneasy peace. Rigorously researched and evocatively written, What Soldiers Do analyses the centrality, both material and symbolic, of women and their bodies to France’s ambiguous relationship as a liberated but dishonored nation with the newly dominant American victors and demonstrates yet again—in disturbing detail—how much ‘foreign affairs’ are indeed about sex and gender.”

(Atina Grossmann,

Cooper Union )

“This is a book that matters. It will provoke heated discussion and critical responses from those who are made uncomfortable by its arguments, and those arguments merit engagement both by those who agree and by those who might not want to face the evidence that the author has gathered so expertly. The prose is bracingly clear, the argument is free of sensationalist exaggeration, and, most important, it is persuasive. This remarkable book deserves to be widely read.”

(Joshua Cole, University of Michigan)

“This remarkable book attacks the myth of the ‘Greatest Generation’ by showing that young Americans went to war in Europe to find sex rather than to sacrifice themselves for Europe’s salvation. It stands as a corrective to all the best-selling celebratory renderings of World War II in the United States over the past quarter century. It will be shocking and controversial.”

Читать дальше