To Duisberg’s enthusiasm and the productive power of the IG was added the genius of Germany’s leading industrial scientist. The man today generally credited as the ‘father’ of chemical warfare was the head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin: Fritz Haber. Forty years old, a brilliant chemist, a future Nobel Prizewinner and a fervent patriot, Haber energetically set about the task of finding the world’s first, practical, lethal chemical weapon. Work began in the autumn of 1914. ‘We could hear,’ stated a witness at the end of the war, ‘the tests that Professor Haber was carrying out at the back of the Institute, with the military authorities, who in their steel-gray cars came to Haber’s Institute every morning… The work was pushed day and night, and many times I saw activity in the building at eleven o’clock in the evening. It was common knowledge that Haber was pushing these men as hard as he could.’ 12In one of these early experiments a laboratory was blown up killing Haber’s assistant, Professor Sachur.

By January Haber had a weapon ready to show the Army. Instead of filling the chemical into shells, he proposed to discharge it from cylinders. The chemical he chose was chlorine, a powerful asphyxiating gas which could be easily stored in the cylinders in liquid form; on contact with the air it evaporated into a low-hanging cloud which, with a favourable wind, could be carried into the heart of the enemy’s positions. In addition, there were large stocks of chlorine to hand. Even before the war, the IG was producing forty tons per day; British production was less than a tenth of this.

The shock of the new weapon, the scale upon which an attack could be mounted, and the ability of gas to penetrate even the strongest fortifications, gave the Germans great hope that chemical warfare might end the deadlock in the west. Haber himself went to Ypres to supervise the attack. Yet despite the fact that between 22 April and 24 May, 500 tons of chlorine were discharged from over 20,000 cylinders, the Allied line held. Gas could not win the war alone – it had to be backed by a powerful offensive, which at Ypres the Germans failed to mount. Haber was bitterly disappointed. The military commanders, he wrote later, ‘admitted afterward that if they had followed my advice and made a large-scale attack, instead of the experiment at Ypres, the Germans would have won.’ 13

Haber returned to Berlin where his wife Clara pleaded with him to give up his work and stay at home. Haber refused. In May he left for the Eastern Front where in three devastating attacks forty miles west of Warsaw the Russians lost around 25,000 men killed and wounded. Throughout the war the poorly-protected Russians suffered the worst of all the countries engaged in the chemical war: by the end of the war they were said to have suffered almost half a million casualties. In just one of the early attacks the Siberian Regiment was virtually eliminated – it began with thirty-nine officers and 4,310 men; it ended with four officers and 400 men. 14

In the west, however, it was the Germans who were about to suffer. Duisberg had made a fatal miscalculation about the Allies’ inability to respond with chemical weapons. Far from breaking the stalemate as he and Haber had hoped, gas was to become a major part of it. A pattern was established which was to persist to the end of the war: the Germans would initiate the use of a new gas to try to break through; it would fail, be copied by the Allies, and the cycle would repeat itself. In the summer of 1915, as work began in the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on the next war gas – phosgene – Foulkes struggled to find the men and material for the Allies’ first gas attack – using chlorine.

Haber himself was left to mourn the personal cost of his work on chemical warfare. On the night that he left for the Eastern Front, Clara Haber committed suicide.

And so, by a combination of industrial might, military expediency, and the skill of a handful of patriotic scientists, the world drifted into chemical warfare. Britain’s poison gas offensive was waged by an elite section of the army, raised by Foulkes and known as the Special Companies (later the Special Brigade). Everyone was given extra pay and all held a rank at least equivalent to corporal. Most of them were new recruits, science graduates or industrial chemists. After the war many of them became key figures in Britain’s fledgling Imperial Chemical Industries. In 1915 they carried revolvers instead of rifles, were largely excused the discipline of the parade ground, and learned instead to handle the ‘oojahs’, the great 190 lb cylinders of chlorine which required two men to carry them and which were to be the basis of Britain’s first chemical attack.

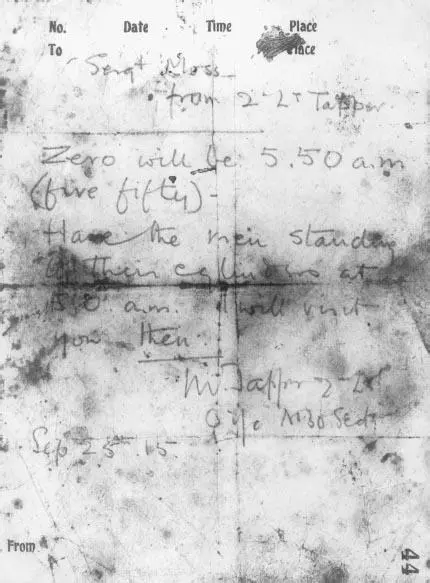

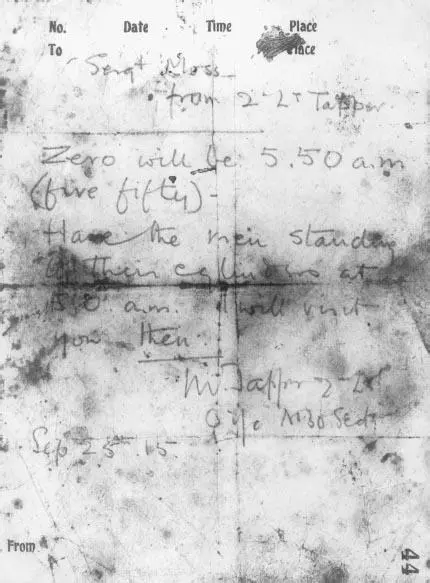

By 25 September, 5,500 of these cylinders, containing 150 tons of gas, had been manhandled into position at Loos in Belgium ready for the British offensive. They had been shipped across the Channel in the greatest secrecy, each in an unmarked wooden box carried at a cost of twelve shillings each. A patrol of aeroplanes ensured that the Special Companies were not observed as they prepared the attack.

The need for surprise was paramount. In all plans for the attack distributed to company commanders, gas was referred to simply as ‘the accessory’, and severe penalties were imposed on anyone who accidentally described ‘the accessory’ as gas. The attitude of most officers to ‘the accessory’, and to the ill-assorted soldiers in charge of it, was well summed up by the old-school Captain Thomas in Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That :

Thomas said: ‘It’s damnable. It’s not soldiering to use stuff like that, even though the Germans did start it. It’s dirty, and it’ll bring us bad luck. We’re sure to bungle it. Take those new gas-companies – sorry, excuse me this once, I mean accessory-companies – their very look makes me tremble. Chemistry-dons from London University, a few lads straight from school, one or two NCOs of the old-soldier type, trained together for three weeks, then given a job as responsible as this. Of course they’ll bungle it. How could they do anything else?’ 15

Yet, for all the suspicion, Foulkes could, on the eve of the Battle of Loos, look back on a remarkable achievement. Five months after the German initiation of gas warfare had caught the Allies by surprise, he had 1,404 men, including fifty-seven officers under his command. As they moved into position at midnight on the 25th, Foulkes waited nervously at Sir Douglas Haig’s battle headquarters at a nearby château, a large-scale trench map spread out on the table in front of him, with small flags representing each of his commanders. At 5 am Haig considered calling off the attack. The wind was so slight that stepping into the grounds of the château, he asked one of his officers to light a cigarette; the puff of smoke scarcely drifted in the still morning air. Nevertheless, the attack went ahead. At 5.50 am the cylinders were opened. One gas officer, in a sector where the wind was least favourable, refused to discharge the gas. His refusal was relayed to Headquarters who instructed him to do as he was told. A few minutes later he was horrified to see the cloud drift back, gassing hundreds of British troops.

Graves was scathing about the efficiency of Foulkes’s men in his sector of the front. The spanners they had been provided with for unscrewing the cocks of the cylinders were the wrong size and ‘the gas-men rushed about shouting for the loan of adjustable spanners.’ Only one or two cylinders were released. Warned of the attack the Germans opened fire: ‘direct hits broke several of the gas cylinders, the trench filled with gas, the gas-company stampeded.’

The original order given to Sergeant J. B. Moss of the Special Brigade’s ‘B Company’ on 25 September 1915, instructing him to prepare for Britain’s first gas attack ( Imperial War Museum ).

Things went better elsewhere along the front. An aerial reconnaissance report handed to Haig shortly after 6 am reported that ‘the gas cloud was rolling steadily over towards the German lines’. As the chlorine reached the first trenches, warning drums began to sound along the length of the German Front. In the trenches themselves the scenes were a virtual replay of those at Ypres in April. Officers and men were equally unprepared. Masks had been lost or forgotten, most of the respirators they had were useless (after the attack one British sergeant reported burying twenty-three gassed Germans: all were wearing respirators). German commanders reported complete panic. Men who had been given no rations for four days as a result of the constant bombardment which had preceded the gas attack were already weak and quickly collapsed. Some tried to crouch in dug-outs – these were at first free from gas, but gradually it accumulated and forced them out. Seventy Germans tried to come over the top to surrender but were mown down by their own machine gunners who were better equipped than the ordinary troops, with divers’ helmets and oxygen cylinders. Eventually though even they succumbed: their oxygen supply lasted thirty minutes; by carefully interspersing the clouds of chlorine with waves of smoke, the British padded out the attack to forty minutes. The smoke had an additional psychological effect, blotting out the autumn morning with a fog so thick that as far back as four miles behind the German line visibility was less than ten paces.

Читать дальше