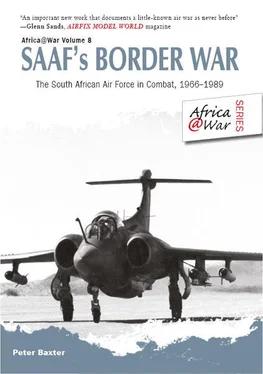

Peter Baxter - SAAF's Border War

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Baxter - SAAF's Border War» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Solihull, Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Helion & Company, Жанр: military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:SAAF's Border War

- Автор:

- Издательство:Helion & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- Город:Solihull

- ISBN:978-1-908916-23-5

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

SAAF's Border War: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «SAAF's Border War»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

SAAF's Border War — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «SAAF's Border War», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The SAAF played a very limited role in the operation. Apart from a long-range Canberra bombing sortie, flown to support elements of the FNLA under Holden Roberto during an ill-advised attempt to capture Luanda from the north on the eve of the national independence – the disastrous Battle of Quifangondo – the distances were found to be too great for the deployment of useful offensive operations in support of ground troops. Instead Cessna 185 aircraft were used in a light communication role and, of course, the ubiquitous Puma helicopter was consistently deployed in battlefield support, with one ship being recorded lost, taken down on 22 December 1975 by anti-aircraft artillery originating from a hillside some 18 kilometres northwest of Cela in the Cuanza Sul Province. In this instance, the pilot and crew effected a successful forced landing after which, some 50 kilometres ahead of the SADF farthest north, evaded capture for 22 hours before finding their way back to safety.

Such was not the case a few weeks earlier when a C-185 spotter aircraft was shot down over Ebo, also in the Cuanza Sul Province, during the tense battle for that town. Two pilots and an air observer were killed in what transpired as the first de facto defeat of the advance. Despite many efforts in the aftermath of this incident, the remains of the three aircrew have never been recovered.

The area in which the SAAF provided invaluable support was in air transport and resupply. Here the heavy lifting was undertaken mainly by the pilots and crews of 28 Squadron, shuttling the squadron fleet of ever-dependable C-160 Transall and C-130 Hercules transporters back and forth from Angolan airstrips, carrying personnel, ammunition, rations and casualty evacuations. At one point it was recorded that the transport fleet was operating out of the Cela airfield more or less on a 24-hour basis, with one crew registering over 100 hours of flight time over a 12-day period, significantly more than the legal limit.

Ultimately the South African advance was halted by a combination of bridges destroyed by retreating enemy and a rapid escalation of Cuban military support for the MPLA and its military wing FAPLA. It is also fair to say that a severe bout of political jitters affecting previously committed regimes, not least among them the United States, contributed much to a change of heart in Pretoria. The question now had to be asked: what would South Africa have done with Luanda should it have succeeded in taking the city? She could hardly have hoped to occupy Angola and certainly she would not have been able to hold onto the capital city for long. Moreover, the unpublished US guarantees and promises that had inspired Pretoria to undertake such an ambitious military expedition were now clearly no longer relevant, and with much lowing in the OAU pen regarding the legitimacy of the MPLA, and with a general acceptance internationally that this was so, there seemed little point in South Africa leaning further out on a limb to make a bad job good. Castro, it seemed, had dramatically raised the stakes on behalf of the Soviet bloc, called the bluff of the West and had won. Angola now lay within the Soviet–Cuban sphere of influence and there was nothing for it but for South Africa to effect an orderly withdrawal, conceding each district back to the MPLA as it did.

The best that could be said about it all was that South Africa now had a new regional ally in UNITA which, in fairness, was scant compensation for the loss of an old regional ally in Portugal and the arrival of SWAPO in liberated Angola with all the material and moral support that the MPLA and the Cubans and Soviets could offer. The FNLA had effectively dissipated in the aftermath of the disastrous defeat at Battle of Quifangondo which, incidentally, saw the South African support contingent evacuated from the coastal town of Ambrizete, some 150 kilometres north of Luanda, using inflatables and a SAAF Westland Wasp helicopter to shuttle men on board the SAS President Steyn in a combined South African naval and air force operation.

CHAPTER FOUR:

THE COLLAPSE OF PORTUGUESE RULE IN AFRICA: A NEW ERA AND A NEW ENEMY

Perhaps the most important lesson to be absorbed by South Africa in the aftermath of Savannah was how disadvantaged in the matter of equipment, armour and technology the defence establishment was after some 30 years of military malaise. The campaign had illustrated very clearly the limitations of guts and glory in the face of the sophisticated Soviet weaponry that was pouring into Angola and into the hands of FAPLA front-line units. South African artillerymen, as only one example, had on more than one occasion during Operation Savannah found themselves comprehensively outranged by their opponents and had only managed to keep one step ahead thanks to excellent training and very nimble tactics. The same was true in terms of air support, armoured vehicles and tanks, all of which prompted military planners at home to begin to give serious thought to plugging the gaps.

The difficulty, of course, was that South Africa was finding herself increasing constricted by the United Nations arms embargo and a general unwillingness on the part of key global arms suppliers to deal with the country. Britain, with its titanic post-colonial conscience, was among the first to restrict arms supplies to South Africa – ironic, many were apt to grumble, bearing in mind that South Africa had managed to overcome a natural aversion to the British in order to defend her empire in two world wars. South Africa, however, owned a fledgling arms industry which, ironically again, owed its existence to British encouragement and capital and which had produced a considerable amount of support matériel for the general Second World War Allied effort.

South Africa had begun, as we have heard, to fall from grace in the aftermath of the 1948 general election that introduced the National Party into power and which began the process of institutionalized apartheid that the global community would in due course begin to find so unpalatable. This increasingly negative sentiment on the part of various global forums peaked as a consequence of the March 1960 Sharpeville Massacre that saw some 69 blacks gunned down by police during an anti-pass law demonstration. The United Nations was finally nudged awake from an unquiet slumber over the matter of creeping South African race dichotomy and began issuing ever-more shrill edicts condemning the regime and encouraging voluntary international sanctions, in particular an arms embargo.

That Britain was among the first to respond perhaps goes some way to explain the South African choice of the French aircraft manufacturer Dassault Aviation for the acquisition of the substantial fleet of Mirage IIIs and F1s. The former were acquired in the early 1960s and included CZ interceptors, EZ ground-attack, BZ and DZ dual-seat trainers as well as photo-reconnaissance RZ versions of the aircraft. The decision to acquire an additional fleet of F1s was taken in 1969 but these did not begin to arrive in South Africa until 1975 and were unavailable at the time of Operation Savannah . The jet fighter force in fact only deployed permanently during the latter phases of the Border War, namely between 1978 and 1988.

In the meanwhile, an armaments production board had been established in 1964 for the purpose of controlling and monitoring general arms procurement, supply and manufacture for the SADF, South Africa at that point having shed the Union and established itself as a republic. Four years later the Industrial Development Corporation helped to establish a parastatal entity, the Armaments Development and Production Corporation, or Armscor, tasked with bringing together the many disparate elements of production, to establish new branches where needed and to oversee all arms imports and exports.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «SAAF's Border War»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «SAAF's Border War» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «SAAF's Border War» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.