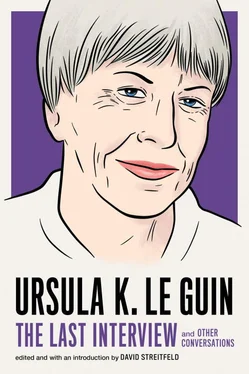

Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Melville House, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, sci_philology, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations

- Автор:

- Издательство:Melville House

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-61219-779-1

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

By the way, I have finally come up with a name for books like Four Ways and Searoad —stories that are genuinely connected by place and/or theme and/or characters. Such a book is a story suite, on the analogy of Bach’s cello suites. The story suite is a common enough form, particularly in science fiction, that I wish (dream on!) could be recognized as such—not labeled and dismissed as a collection, certainly not as a “fix-up,” but seen as a genuine fictional form in its own right, conceived as such not patched together, and with its own intriguing and complex aesthetic.

GEVERS:“Coming of Age in Karhide” is an unexpectedly direct return to the setting of The Left Hand of Darkness. Is it a sequel to that famous novel, or more of an anthropological footnote to it?

LE GUIN:Well, a short story can’t be a sequel to a novel, but it can follow from it (sequitur)—no? If it’s a footnote, I wouldn’t call it so much anthropological as sexual. It seemed high time we got all the way into a kemmerhouse. With a native guide, instead of a poor uptight Earth guy trying to figure out what’s going on and being disturbed by it… Left Hand gives the reader very little opportunity to experience being double-gendered, since Estraven is mostly in somer; there’s only a brief, though crucial, scene involving kemmer, and most of that is from Genly’s POV. I wanted to explore it as a natural, universal experience, instead of a weird alien condition. Back in 1968, I and most readers needed Genly Ai’s POV to mediate the strangeness. I don’t think we do, now. (Si muove lente, eppur si muove!)

GEVERS:“The Matter of Seggri” is perhaps the most experimental of your late Hainish tales, a particularly radical and affecting take on gender relations. What inspired its male-scarcity scenario, and your decision to employ such a multiplicity of narrative voices?

LE GUIN:I kept reading about how many female fetuses were being aborted in India, China, and other societies where the only baby worth having is a male, and about the future surplus of men and deficit of women if the trend continues. My bent imagination bent this whole scenario around and produced a great surplus of women, which biologically speaking is of course far more practical, but humanly speaking…? Well, that is where the imagination actually gets to work. Producing a story. A set of stories. As many stories as there are people… Hence, perhaps, the variety of voices.

Many of my works since the 1980s have used multiple narrative voices in various ways. I often find this multiplicity an essential tool to storytelling at this point. Also, it can lead, paradoxically, to brevity; and I’m very fond of the novella length. There is certainly material enough for a novel in “Seggri,” but I liked keeping it short, allusive, suggestive. Have had enough of novels where one voice yatters on and on…

GEVERS:The O stories—“Mountain Ways” and “Unchosen Love”—are (like the earlier “Another Story”) set in a society divided into two elaborate moieties and practicing a profoundly cumbersome marital system. Would such a four-person hetero- and homosexual menage be practical? Or is this “sedoretu” system a thought experiment, a satiric or parodic construct?

LE GUIN:Well, writing the stories, I thought of the sedoretu as pure thought-experiment—a highly enjoyable tool for exploring human relations and emotions. I hadn’t exactly thought of it as satirical. We are so good at making life difficult for ourselves, not least by inventing almost impossible customs. Monogamous lifelong heterosexual marriage is such a peculiar institution that it hardly seems to need to be made fun of. But of course if you make marriage even harder than it is, involving four people instead of two, and homosexuality as well as heterosexuality, it gets even more interesting. At least, it does to me. But I find all cumbersome cultural constructs and customs interesting. I am an anthropologist’s daughter, after all.

You ask if the sedoretu would be practical. I don’t know. Is monogamous heterosexual marriage practical? I don’t know. My husband and I have done it for forty-eight years, but that could just be luck, and a bit of practice.

GEVERS:“The Birthday of the World”: is this a retelling of sorts of the Spanish conquest of Peru? Does the story form part of the Hainish Cycle?

LE GUIN:Certain aspects of the society in the story were borrowed from Incan Peru, and the absoluteness and suddenness of the social collapse resemble what happened to the Incan Empire when the Spanish came, but it’s not meant to be a commentary in any way on that society and that event. I guess it’s partly a meditation on the also noteworthy fragility of our cultural constructs. Whether it’s an Ekumenical story I honestly don’t know. It could be.

GEVERS:Who, for you, are the finest SF authors now writing—both your fellow feminist writers and more generally?

LE GUIN:First I am to list fellow feminists and then… non-fellow anti-feminists? Come on, Nick, let’s get out of the pigeonholes. If feminism is the idea that differences between the genders, beyond the strictly physiological, are an interesting subject of study, but have not been determined, and so are not a sound basis for society to use in prescribing or proscribing any proclivity or activity—which is what I think it is—then I probably don’t read any non-feminist SF writers, these days. Do you? Anyhow, I hate trying to answer this who-do-you-like-best question, because I always leave out people I meant to mention, and then kick myself later. Allow me to dodge this one, okay?

GEVERS:You’ve been writing fascinating “Interplanary” sociological portraits for a while now. When do you expect to assemble these into Changing Planes ? And what other projects lie on the horizon?

LE GUIN:Thank you for asking, and for calling those stories fascinating. I have been afraid people might find them infuriating. They certainly exemplify my fine disregard for plot. Perhaps they will puzzle some of my critics, who treat my work as if it had all the comic possibilities of a lead ingot. Anyhow, the manuscript is out; it is in the hands of the agents, the publishers, the editors, the Fates, the Furies, whoever. I hope there will be a book of Changing Planes.

But changing planes isn’t quite what it was before the eleventh of September of this year, is it?

At the moment I am working hard to complete a translation of a fairly large portion of the poetry of the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral. After that, quien sabe ?

SONG OF HERSELF

INTERVIEW BY BRIDGET HUBER

CALIFORNIA MAGAZINE

SPRING 2013

Ursula K. Le Guin has said that her father, Alfred Kroeber, studied real cultures, while she made them up. Indeed, many of the writer’s most celebrated novels are set in intricately imagined realms, from the sci-fi universe of Ekumen to the fantasy archipelago of Earthsea.

This inventor of worlds grew up in Berkeley. Her father was the University of California’s first professor of anthropology. Kroeber Hall, the campus building that houses the department, is named in his honor. A pioneer of cultural anthropology, today Professor Kroeber is best remembered for his association with and research on Ishi, the man believed at the time to have been the last of the California Yahi tribe. He was even called “the last wild Indian in North America.”

That was the subtitle, in fact, of the book Ishi in Two Worlds, written by Le Guin’s mother, Theodora Kroeber, who met Le Guin’s father while she was a graduate student at Berkeley. The book made her famous in her own right. Now in a fiftieth anniversary edition from UC Press, Ishi in Two Worlds has sold more than one million copies.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.