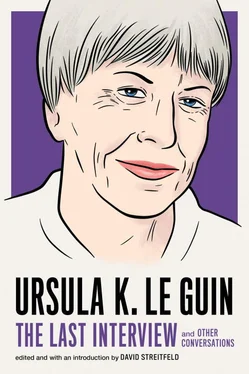

Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Melville House, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, sci_philology, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations

- Автор:

- Издательство:Melville House

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-61219-779-1

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Le Guin and her three older brothers grew up in a Bernard Maybeck house on Arch Street, not far from campus. She remembers life there as “easygoing and generous” and that the family home was filled with the conversation of “interesting grown-ups”—including academics, intellectuals and the members of various California Indian tribes.

California Magazine caught up with Le Guin as she was preparing to come to the Berkeley campus to deliver the 2013 Avenali Lecture. The event, sponsored by the Townsend Center for the Humanities, was entitled “What Can Novels Do? A Conversation with Ursula Le Guin.”

What follows is an edited transcript of our own conversation with the Berkeley native about being a child, a mother, and a grandmother—in short, about growing up and growing old.

BRIDGET HUBER:Does a return to Berkeley bring back a flood of memories?

URSULA K. LE GUIN:I grew up in the 1930s and ’40s, and Berkeley was a rather small city then. It didn’t have the reputation that it got later of being extremely leftist, liberal, independent. It was just kind of a more conventional university town. It was an extremely nice place to be a kid. I could go anywhere. My best friend and I, we played all over the campus, and the campus wasn’t all built up yet, you know? There were lots of lawns and forests, and Strawberry Creek was like a little wild creek. It was a wonderful place to play.

HUBER:Wasn’t Berkeley somewhat bohemian even back then?

LE GUIN:There was room for bohemians in it, but it was really pretty middle class. Not rigidly middle-class like you might get in the Midwest; there was a lot of latitude always in Berkeley, and in the thirties and forties of course it was full of refugees from Europe because the university had a wonderful policy of taking in intellectuals who were running from Hitler or Mussolini. I do believe that influx of brilliant European minds may have stirred the city up a bit.

HUBER:How would you characterize your parents’ parenting style? How did they raise you?

LE GUIN:Well, I think they did a real good job. [ Laughs ] They were very loving and very patient, but they didn’t hover. I wasn’t very rebellious because there wasn’t anything to rebel against. It was kind of easy to be a good girl. And I had three big brothers, and that was kind of cool, too.

HUBER:Were you children part of the dinner table conversations at home?

LE GUIN:As soon as we got old enough. I think until we were about five we’d eat upstairs with my great-aunt Betsy, who lived with us. I think from about five on we were considered civilized. Then Betsy got to come downstairs with us. [ Laughs ] We were all there at dinner, and there was always conversation at dinner. In that sense, it probably seems very old-fashioned to people now.

HUBER:I was struck by your description of the teenage summers you spent at your family’s ranch, wandering the hills alone. You said about it, “I think I started making my soul then.” Why are experiences like that important for kids to have?

LE GUIN:It does seem that, in the last twenty years or so, children get extraordinarily little solitude. Things are provided to do at all times, and the homework is so much heavier than what we had. But the solitude, the big empty day with nothing in it where you have to kind of make your day yourself, I do think that’s very important for kids growing up. I’m not talking about loneliness. I’m talking about having the option of being alone.

If you’re a very extroverted person, you probably don’t want that. But if you’re on the introverted side, you’re not given much room in the world we’ve got now. You’re kind of driven into this whole sociability of the social media. Texting is wonderful for teenagers. I was on the telephone all the time when I was thirteen, with my best friend. Gabble gabble gabble gabble. I mean, what do teenagers talk about? I don’t know, but they need to do it. Texting looks like a wonderful way to do that, to just be in touch with each other all the time. But I think it’s important that there also be the option not to be in touch for awhile, to just drop out. How do you know who you are if you’re always with other people doing what they do? That’s true all through life; it’s not just kids.

HUBER:So you would argue that we should try to give kids more space.

LE GUIN:Yeah, give them some room. Give them room to be themselves, to flail around and make mistakes. I had lots of room given me, so at least I know enough to value it.

HUBER:Did your parents encourage you to write?

LE GUIN:Not exactly, they just saw I was doing it and they would say, “Hey, that’s fine. Go ahead.” But I was left very, very free. I had encouragement, but no pushing.

HUBER:Much has been made of the connection between your father’s profession as an anthropologist and the nature of your fiction. How do you think his work influenced yours?

LE GUIN:I’m not sure that his work influenced mine, because I didn’t really know his work until I was well into my twenties and thirties and began reading him. But I was formed as a writer earlier than that, to a large extent. My father and I had certain similarities, intellectually and temperamentally. We’re interested in small details, in getting them right. We’re interested in how people do things and what things they do and how they explain doing them. This is all kind of anthropological information. It’s also novel information. It’s what you build novels out of: human relationships, how people arrange their relationships. Anthropology and fiction, they overlap to a surprising extent.

HUBER:Was Ishi’s story a big part of your consciousness growing up?

LE GUIN:No, I honestly knew nothing at all about Ishi until they asked my father to write about him and he sort of gave the job to my mother, and then she began researching him. This was in the very late fifties. Ishi died in 1916. I wasn’t even born until 1929. My mother never knew Ishi. It was something way back in my father’s life, and it was not a happy memory, I think, because of the way it ended. No. He had to feel very bad about the fact that Ishi died of white man’s TB. My father did not reminisce. He wasn’t one of those people who talked about old times. But I think there was some pain there that he didn’t want to go back to. He was out of the country when Ishi died, and that always—they were friends, after all. That’s always hard, to feel like, “I let him down.” This is just guesswork on my part. He didn’t want to talk about it, and it’s not the kind of thing I would’ve asked him.

HUBER:What do you think about the way that Ishi was treated, and his relationship with your father?

LE GUIN:That’s two different questions. One, the relationship was, as I can understand it, a deep friendship within this curious constraint of their sort of formal relationship. Ishi was an informant and an employee of the museum, and my father was a professor. It was a more formal age, remember. The general question of how it was handled… I have to say, I think they did about the best they could in the circumstances. They got Ishi a job. He had work to do within this white world that he’d been dumped into. And a place to live, which apparently he liked, and he could meet the public and try to show them what being a Yahi was. I realize it has come in for enormous criticism from generations who have a lot of hindsight and say, “My goodness, they were exploiting him, and they could have done it different,” and so on, but they never convinced me that anybody then knew how to do it any better than they did. But it is a heartbreaking story.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.