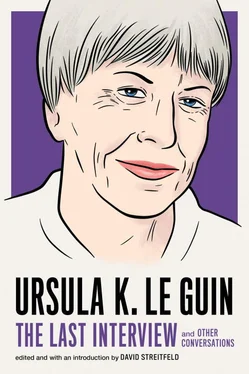

Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Melville House, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, sci_philology, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations

- Автор:

- Издательство:Melville House

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-61219-779-1

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Any refusal to accept the abuse of the world by ill-considered, misapplied technologies as desirable/inevitable can be labelled Luddite. All genuine alternatives to Industrial Capitalism can be, and are, dismissed as “nostalgia.”

All ideals are positively dangerous. All idealists are dangerous: Pol Pot, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jefferson, Lenin, Osama Bin Laden, Francis of Assisi.

What is endangered, and how it is endangered may, however, vary.

And there may be a difference—a subtle one, a crucial one—between idealists and ideologues.

GEVERS:The fate of Earth in the Ekumen series is not exactly apocalyptic, but quite bleak, blighted, and theocratic, as hinted in The Dispossessed and shown in more detail in the story “Dancing to Ganam” and The Telling. How close is this portrait to your actual expectations for the planet?

LE GUIN:I don’t know. Sometimes I think I am just trying superstitiously to avert evil by talking about it; I certainly don’t consider my fictions prophetic. Yet throughout my whole adult life, I have watched us blighting our world irrevocably, irremediably, and mindlessly—ignoring every warning and neglecting every benevolent alternative in the pursuit of “growth” and immediate profit. It is quite hard to live in the United States in 2001 and feel any long term hopefulness about the unrelenting use of increasingly exploitative and destructive technologies: not so much weaponry, at this point, as technologies that could and should be useful and productive—fuel sources, agriculture, genetic engineering, even medicine. And, of course, we keep breeding.

Dark visions of a theocratic world have been fueled by the rise, during the last two or three decades, of the fundamentalist side of every world religion, and the willingness of many people to believe that fundamentalism is religion.

I might point out that the unhappy Earth hinted at in some of the Ekumenical fictions would be only a dark passage on the way to the very far future Earth of my most hopeful book, Always Coming Home. Believing that we have no future but that of high-tech development, urgent expansion, urbanization, and ruthless exploitation of natural and human resources—believing that we have to go on as we are going now—people tend to see that book as backward-turning. It isn’t. It looks at, but not back. It’s a radical attempt to think outside current assumptions, a refusal of them. It’s an attempt to portray a genuinely mature society. To imagine a “climax technology,” the principle of which would not be enforced growth, but homeostasis. To offer not a mechanical but an organic model for culture.

GEVERS: The Telling could be read as a science-fictional allegory of the plight of the Tibetans under Chinese rule, or more broadly of the suppression of traditional wisdom under Communism of a corporatist sort, as in China as a whole. Does this mean that such traditional wisdom (theocratic in nature in Tibet) is infallible, or exempt from criticism in its turn?

LE GUIN:Actually, it was not Tibetan Buddhism, but what happened to the practice and teaching of Taoism under Mao that was the initial impetus of the book. I was shocked to find that a twenty-five-hundred-year-old body of thought, belief, ritual, and art could be, had been, essentially destroyed within ten years, and shocked to find I hadn’t known it, though it happened during my adult lifetime. The atrocity, and my long ignorance of it, haunted me. I had to write about it, in my own sidelong fashion.

I don’t know why you ask if I “mean” that any traditional wisdom, or any theocracy, is infallible or exempt from criticism. The Telling is indeed shown as a flexible and rather amiable tradition, very attractive to our point-of-view character; but she and I and they leave infallibility to popes. The Telling has no clergy, even: only people who take on ritual function at certain times. The tradition has no god, gods, hierarchical worship, or prayer. Because she is in the process of discovering it little by little, and because it is a badly damaged, currently illegal tradition, barely clinging to existence, Sutty has no basis from which to criticize it, and no particular reason to do so. But she does remain on the look-out for religiosity of the kind she knew on Earth, which she detests and distrusts with all her heart. Surely the novel does not show the Unist theocracy governing Earth as wise, infallible, or above criticism?

Your question sounds as if you kept thinking “Tibetan Buddhism,” and did not believe what I was telling you in the book. An example of why the practice of “telling” takes quite a lot of practice… as it implies listening…

GEVERS: The Other Wind completes a retraction or renunciation, begun in Tehanu and Tales from Earthsea, of the premises of the original Earthsea trilogy: magic itself is invalidated to a great degree. How do you intend the first three books to be read now? In their spontaneous, shall we say, majesty, or with the qualification of hindsight?

LE GUIN:Well, Nick, and when did you stop beating your wife?

The assumptions stated in the first sentence of this question are simply wrong, which means that I can’t answer but can only retort with questions.

Why do you say magic is invalidated in the last three Earthsea books? On what evidence? Because Ged can’t do it anymore—one man, who gave up his power knowing what he was doing and why? Has the School on Roke closed? Have the Old Powers died? Are the dragons grounded? Is the Patterner not still in his Grove, and is the Grove not the still and ever-moving center of the world?

I will not say how I “intend” the books to be read; I have and want no control over my readers, except, of course, the sway of the stories themselves. Different people will read my trilogies different ways and that’s as it should be. Because the first trilogy is more accessible to kids, they may stop with it, and then come back when they grow up, and go on with the second set.

But if the second trilogy invalidated, or retracted, or revoked the first one, I wouldn’t have written it.

The second trilogy enlarges the first, which is very strong but narrow, leaving out far too much of the world.

The second trilogy changes nothing in the first. It sees exactly the same world with different eyes. Almost, I would say, with two eyes, rather than one.

All the books are, in large part, fictional studies of power. The first three see power mostly from the point of view of the powerful. The second three see power from the point of view of people who have none, or have lost it, or who can see their power as one of the illusions of mortality.

GEVERS:Looking now at the stories in The Birthday of the World : “Old Music and the Slave Women” is a continuation of the Werel novella cycle already published [in 1995] as Four Ways to Forgiveness. Is “Old Music” a similarly patterned fifth way to forgiveness, or does it differ in its essence from the earlier Werel/Yeowe tales?

LE GUIN:Thank you for talking about new and recent work. So many people don’t, and I do get weary of answering questions about novels I wrote thirty years ago! Of course, I have developed nice glib answers to the more inevitable questions about them, while I may stammer a bit about the more recent works. “Old Music and the Slave Women” is a fifth way to forgiveness that didn’t get itself written in time to get into the book. It is, however, a bit bleaker than the first four. (See above re: Idealists.) It is a mourning for the horrors of war. Old wars, new wars. Goya’s wars. Our wars.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.