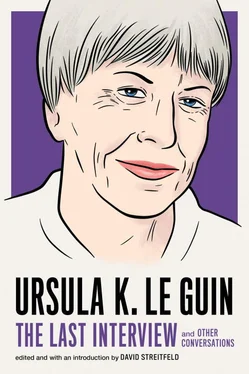

Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Melville House, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, sci_philology, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations

- Автор:

- Издательство:Melville House

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-61219-779-1

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On a street on Urras, Shevek goes shopping for the first time in his life:

Saemtenevia Prospect was two miles long, and it was a solid mass of people, traffic, and things: things to buy, things for sale. Coats, dresses, gowns, robes, trousers, breeches, shirts, blouses, hats, shoes, stockings, scarves, shawls, vests, capes, umbrellas, clothes to wear while sleeping, while swimming, while playing games, while at an afternoon party, while at an evening party, while at a party in the country, while traveling, while at the theater, while riding horses, gardening, receiving guests, boating, dining, hunting—all different…

And the strangest thing about the nightmare street was that none of the millions of things for sale were made there. They were only sold there. Where were the workshops, the factories, where were the farmers, the craftsmen, the miners, the weavers, the chemists, the carvers, the dyers, the designers, the machinists, where were the hands, the people who made? Out of sight, somewhere else. Behind walls. All the people in all the shops were either buyers or sellers. They had no relation to the things but that of possession.

In an unusual move before she had completed the manuscript, Le Guin showed it to a friend, the Marxist critic Darko Suvin, who teaches at McGill University in Montreal. Le Guin believes that Marxists and anarchists are their own best critics, “the only people that seem to speak to each other’s main problems.” He told her, among other things, that she couldn’t have twelve chapters in an anarchist book; she must have thirteen. And he told her that her ending was too tight, too complete. Le Guin added a chapter and made the book open-ended.

When The Dispossessed was finished, Le Guin was exhausted. “I sat around and was sure I never would write again. I read Jung and I consulted the I Ching. For eighteen months, it gave me the same answer: the wise fox sits still or something.”

Since 1974, when The Dispossessed was published, Le Guin has published three short novels, a collection of essays and two collections of short stories. ( The Compass Rose, the most recent, includes a story about the use of electric shock on political prisoners in a country very much like Chile.) Only one of her recent stories takes place in outer space.

“Space was a metaphor for me. A beautiful, lovely, endlessly rich metaphor for me,” Le Guin says looking down toward the docks, “until it ended quite abruptly after The Dispossessed. I had a loss of faith. I simply—I can’t explain it. I don’t seem to be able to do outer space anymore.

“The last outer-space story I did was in The Compass Rose. It’s called ‘The Pathways of Desire,’ and it turns out to be a hoax in a sense. Apparently it’s an expression of my loss of faith.”

She hates the immensely popular science-fiction films of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. “I wouldn’t go to see E. T., to tell you the truth, because I disliked Close Encounters so profoundly.

“It seems so exploitive. I don’t know, his attitude toward people is so weird. At the end of Close Encounters she’s got that beautiful little kid back, you know. He’s been lost for weeks or months, hasn’t he? She’s got her little kid back— what is she doing taking photographs? She doesn’t even have her arm around the kid. It bugs me.”

She pauses and then goes on. “I feel a little weird about standing aside and being snooty because it does seem like they’re not—you can’t talk about them quite like ordinary movies or like an art form. It’s almost like a ritual. People go because other people go. It’s a connection thing, isn’t it? It’s a weird way for people to communicate. But the trouble is, in other words, in a sense it’s like a religious communion, but it’s so terribly low-grade, morally so cheap. Star Wars is really abominable: it’s all violence, and there are only three women in the known universe.

“These films are working on a very low level intellectually and morally, and in their blindness perhaps they do get close to people’s feelings,” she continues, “because they are not only non-intellectual, they are anti-intellectual and sort of deliberately stupid. But I would rather say that about Star Wars. I think Steven Spielberg, on the other hand, is playing a very tricky game. I think he knows. I think he deliberately exploits archetypal images in a way that I really dislike a lot.”

(I ask her how she got through dinner parties when everyone was carrying on about E. T. “I didn’t say anything,” she replies, and then changes her voice to a linebacker’s—“I want to be loved.”)

“I did follow our space flights. The little Voyagers ? God, those were lovely. But what we are doing now I find in itself extremely depressing—the space shuttle. I’m not happy about it the way I was happy about the other ones. It’s all military-industrial. It’s a bunch of crap flying around the world, just garbage in the sky. I think that did have to do with my loss of faith. My God, we could muck that up just as bad as—we’re going to repeat the same…

“I think we’re sick,” she finally says. “I hate to make big pronouncements, but I don’t know how you bring up a kid. There’s the size of our population and people who work so hard, and no one praises them for it. We’ve overbred our species.”

But, I point out, the saving grace for us in many of her books is the presence of others.

“But they don’t have to be human others,” she replies. “We live with others on all sides at all times. That’s the thing about religion, about monotheism. They say we’re other and better. It’s a very silly and dangerous course. It also relates to feminism. Women have been treated as animals have been. If the men insist on talking about it that way, then the men and God can walk in Eden—they can walk alone there.”

She gets up at 5:30 in the morning these days to work on the new book, in the little room at the end of the hall. The population in the book is very small, nearly that of the world in the late Stone Age, a few million here, a few million there, and great herds of animals. There is no hero in the book; there are many, many voices and a female anthropologist named Pandora.

Before I leave, we go out to Sauvie Island to pick blueberries. Finding none to pick, we picnic on the banks of the Columbia. Ursula asks Charles if it was Debbie Reynolds who divorced Eddie Fisher because he brushed his teeth with warm water, and Charles replies no, it was Elizabeth Taylor who divorced Nicky Hilton. She rolls up her pants and stands in the shallow water, the wake of the ships moving in neat waves toward her, each wave a pattern, each one the exact same distance from the next as they stroke the shore.

Mozart heard his music all at once, she had told me earlier, then he had to write it down, to extend it into time.

DRIVEN BY A DIFFERENT CHAUFFEUR

INTERVIEW BY NICK GEVERS

SF SITE

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2001

Ursula K. Le Guin wears many creative hats: as poet, essayist, translator, writer for young children, illustrator, mainstream literary author; but it is surely in her fantasy and science fiction that her especial genius resides. Her two great series, the Earthsea and Ekumenical tales, are ample evidence of that. Earthsea is a many-isled realm of composed and chthonic magics, of dragons and wizards, of frail arrogance and vast humility. The Ekumenical or Hainish Cycle is complex SF, rich in utopian surmise and anthropological reflection. As her recent work is largely preoccupied with matters of Ekumen and Earthsea, it is there that the emphasis of this interview naturally falls.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.