The CAS is headquartered in Lausanne, Switzerland, but the second hearing was held in an office building in New York City. Once again, we made our case before a three-member panel. Only this time, the three were not chosen by the ITF. One was chosen by the ITF, one by my team, and the chairman by the CAS itself. The process was very similar to the first hearing, except we all walked into that room like it was a war. Their lawyers went first. (Oh, how I hate those lawyers with their suits and crooked ties.) Then it was my turn. I spoke for another three hours. I had mixed feelings when it was over. I felt like I’d made my case and the facts were clear, but that’s how I’d felt after the first hearing. So I tried to keep my expectations in check. I almost wanted to feel like shit about it so I’d almost force a different outcome. I do something like this before certain tournaments, too. I spent the next several weeks training, keeping the date of the decision forever in my mind. October 4, 2016. I eyed it like a hawk.

It was a different kind of training than the sort you normally do. When you are competing, you train like a boxer, working your way toward a specific goal, peak performance, which should be reached the day before the fight or tournament. But I had no tournament, which meant I had no such goal. I never wanted to peak, or get too high. I just wanted to maintain, lock myself into a holding pattern that would be broken only when I really knew what the future would look like. In a way, my long, forced hiatus actually helped me. I’d been suffering from all sorts of nagging injuries, aches, and pains. I’d been struggling with my wrist during the first few months of the year, and now it could heal. I’d been playing tennis almost every day since I was four. I’d never simply let my body get better. Now, for the first time in years, I actually began to heal. It was funny. I was banned from competition, but, as a result of that ban, I felt better and more ready to compete than I had in years.

I was in my bedroom in Manhattan Beach when the verdict finally came by e-mail. It arrived at 9:21 a.m. Pacific Standard Time. I knew it was coming, which meant I could not really sleep the night before. I was either running to the bathroom, or tossing and turning, or staring at the ceiling, or willing the hours to pass. I could not stand to read the report right away—I was just too nervous—but the first line in my lawyer’s e-mail gave me a hint. It said the CAS had knocked the ban down from two years to fifteen months. And I’d already served much of it. I screamed when I read that. My father was in Belarus, visiting his mom, but my mom was downstairs. I shouted to her in Russian, “I’m coming back! I will play tennis again. I’m coming back!” Then I called my grandma. Then my father. I was overjoyed, relieved. It was not perfect—nothing is. But a huge weight had been lifted from my shoulders.

The wording of the report was even better than the verdict. They cleared my name in just a few paragraphs. I felt like I’d gotten my air back. My lawyer copy and pasted and highlighted the key paragraphs of the report into the e-mail:

[The] Player did not seek treatment from Dr. Skalny for the purposes of obtaining any performance enhancing product, but for medical reasons.

No specific warning had been issued by the relevant organizations (WADA, ITF or WTA) as to the change in the status of Meldonium (the ingredient of Mildronate). In that respect, the Panel notes that anti-doping organizations should have to take reasonable steps to provide notice to athletes of significant changes to the Prohibited List, such as the addition of a substance, including its brand names.

The Panel wishes to emphasize that based on the evidence, the Player did not endeavor to mask or hide her use of Mildronate and was in fact open about it to many in her entourage and based on a doctor’s recommendation, that she took the substance with the good faith belief that it was appropriate and compliant with the relevant rules and her anti-doping obligations, as it was over a long period of her career, and that she was not clearly informed by the relevant anti-doping authorities of the change in the rules.

Finally, the Panel wishes to point out that the case it heard, and the award it renders, was not about an athlete who cheated. It was only about the degree of fault that can be imputed to a player for her failure to make sure that the substance contained in a product she had been legally taking over a long period, and for most of the time on the basis of a doctor’s prescription, remained in compliance with the TADP and WADC. No question of intent to violate the TADP or WADC was before this Panel: under no circumstances, therefore, can the Player be considered to be an “intentional doper.”

I flew to New York. I was in the city when the findings became public. I had not done an interview in nine months. No comments, no popping off in the media. That press conference had been my last word on all this. I wanted to wait until the last legal word was typed. Now it had been. I went on the Today show and Charlie Rose . I did a big interview with The New York Times. I guess I wanted the ITF to acknowledge their mistake. Instead I got hedging and hems and haws. But that’s OK. It’s something experience has taught me: there is no perfect justice, not in this world. You can’t control what people say about you and what they think about you. You can’t plan for bad luck. You can only work your hardest and do your best and tell the truth. In the end, it’s the effort that matters. The rest is beyond your control.

Here’s another good thing that’s come from all this: I heard from so many fans, so many young girls, who had been inspired by my example and my life. I had never thought of my influence on other people before, how all the work I was doing might pave the way for the next generations, as others had paved the way for me. But I saw it now, and it inspired me. It made me happy and it awed me and of course it made me really want to get back out there and play my game. It’s interesting. Before all this happened I was thinking only about the finish line. How it would end, how I would make my exit. But I don’t think about that anymore. Now I think only about playing. As long as I can. As hard as I can. Until they take down the nets. Until they burn my rackets. Until they stop me. And I want to see them try.

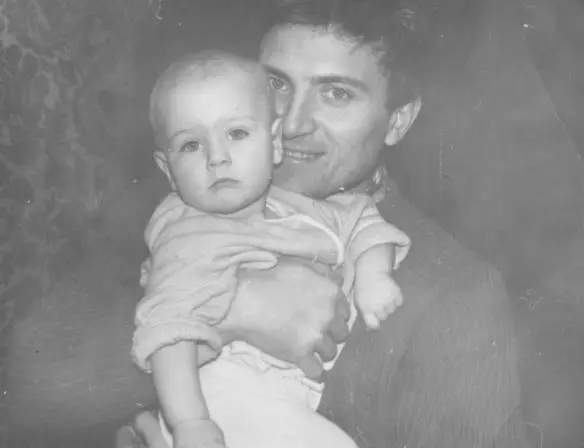

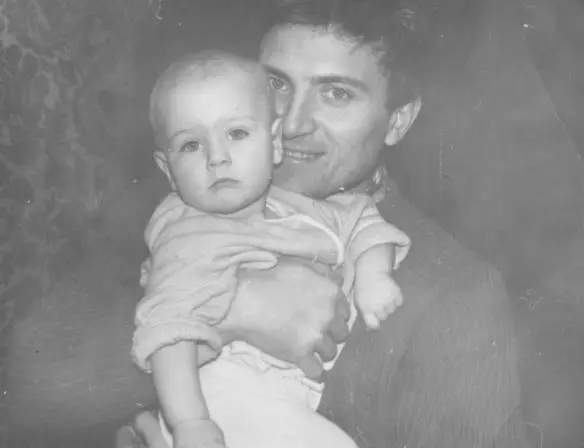

The genuine smile of my father. And the genuine resting bitch face I developed at a young age.

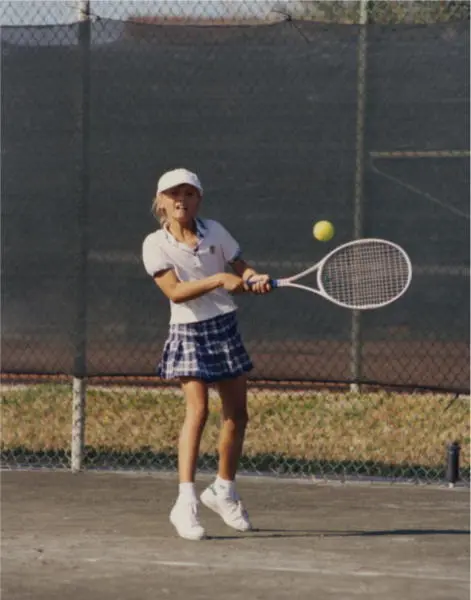

Five years old, on a hot summer day in Sochi, practicing on a public park tennis court. What happened to my shorts?

Our first few days in Bradenton, Florida. Already out on some public courts behind a college. My dad looks like a stud!

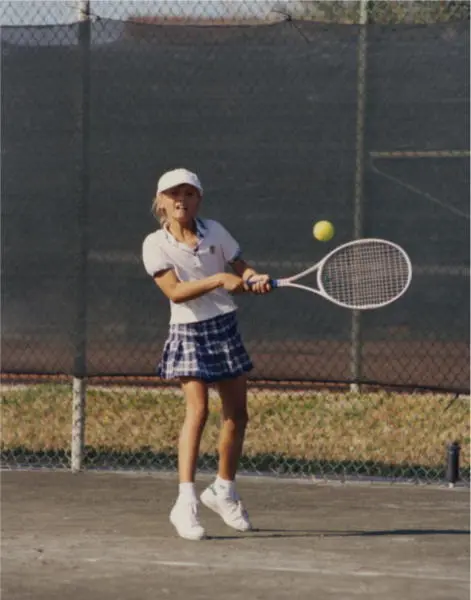

Someone handmade this skirt for me, and I must have worn it five days a week until it ripped. My dad didn’t know how to sew it back together.

May 1994. My first visit to the white sands of Bradenton Beach, wearing a bathing suit my mom packed for me in Russia.

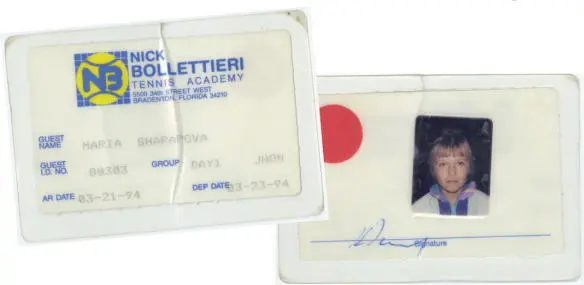

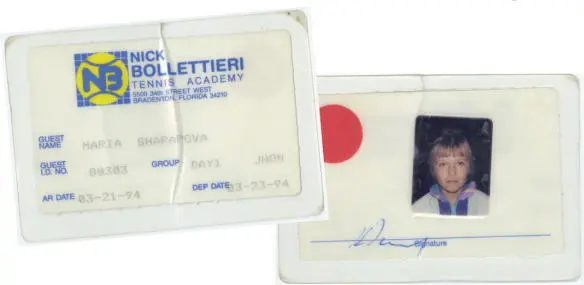

My first ID at the Bollettieri Tennis Academy. My dad had to sign for me, as I didn’t have a signature of my own yet.

This was Herald, my boxing coach. I was eight years old, but he didn’t treat me like an eight-year-old. I did boxing rounds with him and he would throw a ten-pound medicine ball at my stomach to tighten my core.

With Robert Lansdorp. He’s smiling, but he’s probably about to make me run side to side until that basket is empty.

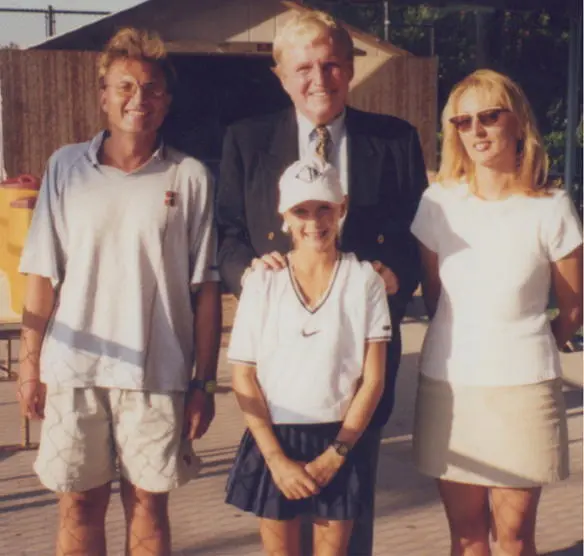

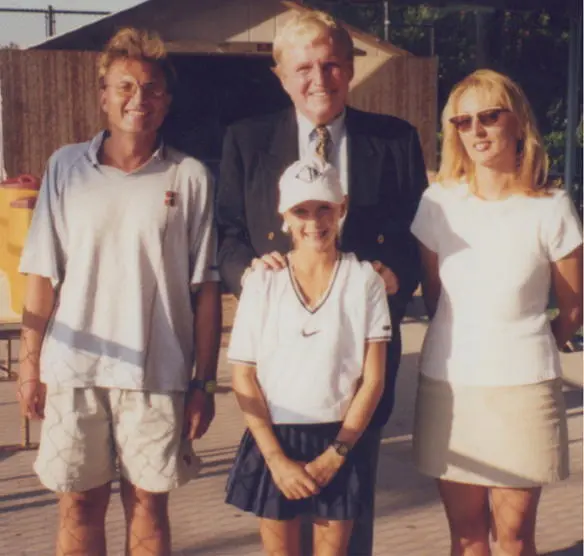

First time meeting Mark McCormack with my parents.

Estelle and me, on our favorite trampoline. Partners in crime, forever and ever.

I was taking my time to get off the court. I’m guessing they kind of liked it.

(Photograph by Alastair Grant, AFP Collection; courtesy of Getty Images)

Disbelief. That first Grand Slam champion moment. At Wimbledon. Seventeen years old.

(Photograph by Professional Sport, Popperfoto Collection; courtesy of Getty Images)

Arriving at the Wimbledon Ball. Hair straight, no makeup. I look so confused, because I am.

(Photograph by Ferdaus Shamim, WireImage Collection; courtesy of Getty Images)

The morning after winning the Wimbledon championship, with the kids of the family who hosted us and my replica trophy.

The first time I beat Justine Henin, and my only U.S. Open championship—so far. In my favorite Nike Audrey Hepburn–inspired dress.

(Photograph by Caryn Levy, Sports Illustrated Collection; courtesy of Getty Images)

Calling my father when I woke up from shoulder surgery. I look miserable. And felt even worse because the journey back had no guarantees.

Carrying the flag at the London Olympics, 2012. I was the first Russian female to ever do so. I will forever be grateful for this honor.

(Photograph by Christopher Morris, CORBIS Sports Collection; courtesy of Getty Images)

Behind the smile of holding the silver medal in London was the wish to go for gold in Rio. It never happened.

(Photograph by Clive Brunskill, Getty Images Sport Classic Collection; courtesy of Getty Images)

When Grigor and I spoke about which picture of us to use for the book, it was inevitable that this would be our choice. Our first-ever picture together, on our first-ever date.

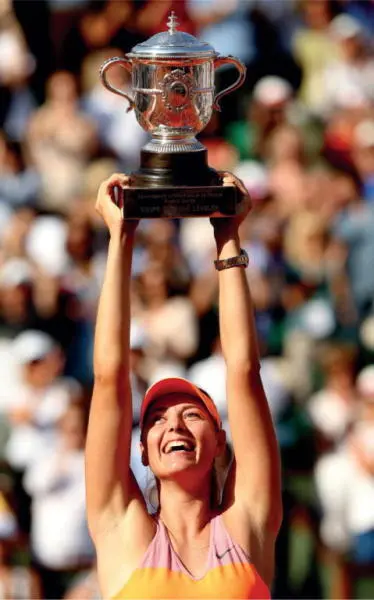

This smile is why I practice every single day. The trophies are beautiful and rare but the smile is internal.

(Photograph by Matthew Stockman, Getty Images Sport Collection; courtesy of Getty Images)

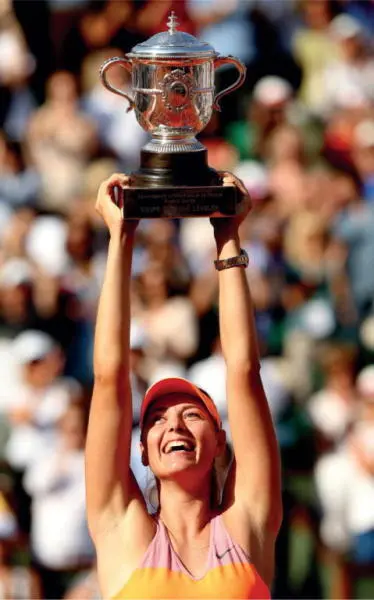

Leaping into the air after my first French Open victory.

(Photograph by Art Seitz)

Читать дальше