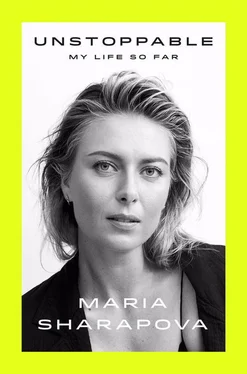

There were maybe fifty reporters and TV people at the press conference. The room was filled with unfamiliar faces and camera crews. There was speculation that I had called everyone together to announce my retirement. I stood before them in a black shirt and a Rick Owens jacket. I felt like I was dressed for a funeral. I had written notes. I looked at them as I tried to explain what had happened in the most direct words I could find:

I wanted to let you know that a few days ago I received a letter from the ITF that I had failed a drug test at the Australian Open. I did fail the test and I take full responsibility for it. For the past ten years, I have been given a medicine, Mildronate, by my family doctor. And a few days ago, after receiving the letter, I found out that it also has another name of meldonium, which I did not know. It’s very important for you to know that for ten years this medicine was not on WADA’s banned list and I had been legally taking the medicine for the past ten years. But on January 1 the rules changed and meldonium became a prohibited substance, which I had not known. I was given this medicine by my doctor for several health issues that I was having back in 2006. I was getting sick a lot. I was getting the flu every couple of months. I had irregular EKG results, as well as indications of diabetes with a family history of diabetes. I thought it was very important for me to come out and speak in front of all of you because throughout my long career I have been very open and honest about many things and I take great responsibility and professionalism in my job every single day. And I made a huge mistake. I let my fans down. I let this sport down—this game, which I’ve been playing since the age of four and love so deeply. I know with this I face consequences and I don’t want to end my career this way and I really hope I will be given another chance to play this game. I know many of you thought I’d be announcing my retirement today. But, if I ever did announce my retirement, it would probably not be in this downtown Los Angeles hotel with this fairly ugly carpet.

I felt so relieved exiting that room. I had nothing to hide and I have nothing to hide. I wanted my friends and fans and even my enemies to know exactly what had happened because it was an inadvertent mistake and I believed they would see it and understand.

I was wrong. Mostly. I mean, yes, some people came to my defense, or at least said, “Well, let’s not rush to judgment. Let’s wait and see.” But the newspapers really went after me, called me a cheater and a liar and compared me with famous cheating athletes. In the course of two news cycles, everything I had ever accomplished had been tarnished. My image, all that I stand for and believe in, all that I have worked for, had been ripped up as if for sport. What does it matter if you are exonerated in the end if you have been destroyed along the way? That’s what people mean when they say the trial is the punishment. Worst is the way this bogus charge made me doubt the world and the people around me. Until now, I had not paid much attention to what was said about me. I had not cared. I figured, “I’ll do my thing, I’ll work hard and play my game, and the rest will take care of itself. The dogs bark, but the caravan rolls on.” But the firestorm that followed the press conference made me doubt that. It was like a worm in my brain, just the worst kind of mindfuck. I’d never felt that way before. Suddenly, no matter who I looked at, I found myself thinking, “Do they know? And do they believe it? Do they think I’m a cheater? Do they think I’m a liar?” For the first time in my life, I was worried what people thought of me.

It really hit me a few hours after the press conference. I was sitting at the kitchen table in Manhattan Beach, talking to my mother, who was making dinner. My phone rang. It was Max. He sounded grave. He had just gotten off the phone with Nike. He did not go into great detail, but simply said, “It was not a good conversation, Maria.” (Anytime Max uses my name something has gone wrong.) Two hours after that, Nike put out a statement, and it was brutal. It was about me, and trust, and role models, and we’re so disappointed. They said that they were suspending me, which I didn’t understand at first. They were a sponsor. They were either affiliated with me or they were not. There was no such thing as a suspension in my contract. Was this part of the shameful scramble of certain businesses and certain so-called friends to put distance between themselves and me, to cover their asses and get clear? When the shit hits the fan, that’s when you can separate the actual friends from the mere acquaintances. Those who flee, let them flee, I told myself. Those who stick, love them. That was a silver lining of this nightmare. It taught me the real from the fake.

Maybe I should have given my sponsors a heads-up before I held the press conference, but I was so determined to not let the news leak, to break it myself. I think what really hurt me was the fact that I had been with Nike since I was eleven years old. They knew me better than any other sponsor in my life. They knew me as a young girl, an athlete, a daughter, and yet their statement was so cold. A few days later, Mark Parker got in touch with Max, who called me to say they wanted to have a conversation. I told Max it was still too raw for me, and that I would call him back when I found the strength.

I was sitting in the kitchen, eating the rice pilaf my mom had made for me (when my mom can’t decide what to do, she makes rice pilaf). I was in a funk, a deep funk, feeling so low I’d have to reach up to touch bottom. A castle made of sand. A house made of cards. That’s what I was thinking when my phone started to buzz. It was a text from my old coach and friend Michael Joyce. I clicked on it, expecting a show of friendship and solidarity, but it was immediately clear that this message was not meant for me. It was probably meant for his wife, but he must have hit my name by mistake. It’s the sort of mistake that makes you think Freud wasn’t so crazy after all. It was just one line—“Can you believe that Nike did that to her?”—but it cut to the quick. It was not just the information, that Nike had suspended my contract, but the tone and the sense I suddenly had of people everywhere, people I had known all my life, speaking about me behind my back, coldly, without affection or warmth, even with a kind of amusement. The fork dropped from my hand. My mom looked up. I wanted to tell her what he’d written, but nothing but sobs came out. That was the moment, the bad moment, the freaked-out vertigo spin moment. I ran upstairs to my room, crying hysterically. I sat there on the floor holding on to my bed for what felt like hours, sobbing. I called Max. He said, “Shhh, shhh, shhh.” He said, “Calm down, Maria, calm down. It’s OK. No, no, no. Nike did not drop you.” My mom spent the rest of the night holding my hand. For the next two weeks, she didn’t let me go to sleep alone.

The next morning was the hinge moment. Either you curl up in a ball, the covers pulled over your head, or you get out of bed and carry on. I’d signed up for an 8:30 a.m. spinning class not far from my house. I was going to meet Sven there. I’d called him at 7:30 and said, “Forget it. I can’t do it. I can’t go.” My eyelids felt heavy. My body felt heavier than it had ever been, even though I’d been losing weight. But something told me I had to go. I had to get out of bed and get dressed and go, make myself do it, or I’d never get out of bed again. This was the moment. Stay down, or get the fuck up. Ten minutes later I sent Sven a text: “I’ll see you there at 8:20.”

I put on some clothes and dragged myself to the car. There were two paparazzi outside the house. Those goddamn Priuses, I never liked that car! They followed me as I drove myself down the hill to the plaza. At the studio, everyone was staring at me, or maybe that was just in my mind. That’s the thing. You start to go nuts. Your own mind turns against you, tortures you. I just got on a bike in that dark room, put my head down, and made myself pedal. Left. Right. Left. Right. I was a mess, a goddamn mess. I cried through the entire class, but I did what I had to do. From that moment, I knew it was going to be awful and unfair but that I’d get through it. Somewhere, deep down, I knew I’d survive.

Читать дальше