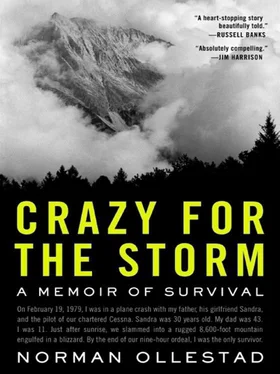

When the snow broke at my waist both hands snapped off the bush and I barely shot my arm up in time to snag the hedge with one hand. My legs fell and lodged in the netting below. Then I got my other hand clutched to the hedge and kicked away the nagging spurs. I lifted my body up into the hedge and snaked my legs deep into its gnarl. I hung to the face of the hedge and it bowed toward the snarling chasm. There was no fucking way I was letting go.

Then I understood that I could drop my legs and swivel from hand to hand along the face of the hedge. I moved, my numb feet tottering like dead stumps over the crust. I traversed the hedge as if swinging from rings in a playground. I made it to the end of the hedge. There was a three- or four-foot gap to the next spate growing out of the snow. I peered through the bush but could not locate the meadow. I knew it was close though.

I reached out with my leg and felt that the snow beneath was firm enough for me to rest some of my weight on it. I gathered my bearing and lowered onto my stomach, spreading my weight. The ground felt solid so I shimmied across the crust and grabbed the next hedge. This allowed me to stand again because I had the hedge to hold onto.

I walked on top of the snow and held on to the hedge so as not to put too much weight on the tenuous crust. The buckthorn spates grew closer and closer together as I moved downslope. I scurried from one to the other and only fell through a couple times. It was easy to pull myself out with the hedge right there. Then I saw the meadow. My eyes fixed on the oasis, nothing else.

AGUARD LET US through the draw gate into Santa Monica Airport. It was desolate. The sky was gray and dull. We parked behind a building underneath the control tower. We walked in. My dad knocked on a door and a man a few years younger than he emerged. His name was Rob Arnold. His sandy blond hair was cut just below his ears and it was combed down neatly, reminding me of those straitlaced guys who came from the city to surf Topanga. He was our pilot. We were all set to go.

WHEN I CAME to the edge of the meadow the snow had compressed the buckthorn, making a four- or five-foot lip on this side of the meadow. I slid over the lip and into the foamy oasis. Wading through the soft snow, moving upright across even ground, shocked me—it broke the spell that had channeled every bit of energy, mental and physical, into one singular focus. I stopped moving. I wanted to give up. Quit. Sit down and refuse to do this. All that I had witnessed over the last eight hours suddenly made me violently angry.

I stood there enraged. The spiking fury kept me from sitting down on the cushioned ground. The anger was hot. For the first time since the crash I didn’t feel cold. My fingers and feet were numb but my face and torso and thighs were actually warm.

Now all that mattered was not getting cold again—and in a flash I was back under the spell that drove me down the mountain and wrenched me out of those buckthorn vines like a wolf smelling fresh meat ahead.

I trudged across the meadow. I searched for an opening in the tight weave of buckthorn and oak trees on the downhill side. I walked the perimeter. The forest was too dense. There seemed no way to get to that road I had spotted from up high. How the hell do you get out of this place?

I saw something but the light was dappled. I ducked under the canopy and kneeled. It was a boot print. Pocking the snow with little squares. Like my dad’s boots. He was still up there getting battered by the blizzard. My knee felt too heavy to lift off the ground, as if squashed by something. His slumped body that wouldn’t flinch when I shook him blurred my thoughts. I was down here and he was way up there. He would have carried me down with him, no doubt in my mind.

I forced myself to study the snow— bear down and grind it out . The boot prints were fresh. There were more.

Narrowing my aim on the boot prints seemed to tuck me back into my wolfish pelt—more natural to me now than my eleven-year-old-boy skin.

The terrain came into sharp focus. I lifted my knee and crawled forward following the prints down the hillside. A chaotic, circuitous route. Kids playing, I guessed. And there’s a big one. An adult. Their dad. I was on my feet, staggering over their trail. It lured me left and right, tunneling me under the cluster of bush, plants and oak limbs. Each square notch in the snow reached into my gut, guiding me forward. The prints would lead to that road.

I heard something. A voice.

PILOT ROB LED us across the tarmac toward one of several four-seater Cessna airplanes lined up in a row. My dad looked up at the flat gray sky.

Do you think the weather’s okay to fly in? he asked Rob.

Yeah. Just a couple clouds, said Rob. We’ll stay below them probably. Should be a smooth flight.

My dad glanced at the sky one more time.

All right, he said.

THE WIND HAD tricked me before, so I ignored the voice. The boot tracks made a circle and I followed it around until I realized I was backtracking. Ripples of panic set off my adrenaline and my body jittered. It was hard to concentrate. I needed to delineate the chaos of prints before me but my head was clouded by the surging adrenaline.

Hello! Anybody there! echoed in the canyon.

I blinked. The voice seemed to come from everywhere. I riveted my eyes to those boot prints, not wanting them to somehow disappear—they were real but the voice might not be. I yelled back.

Help! Help me!

Hello! someone called back, and it didn’t sound like the wind.

Help! I responded.

Keep yelling, said a boy. I’ll follow your voice.

I kept yelling and I ran down the hillside, toward my best estimation of where the voice was coming from. I darted around the small oaks like racing poles. I came out into milky light at the dirt road.

Holy shit. I made it.

As I staggered down the road I called out for the voice.

I heard it coming from just around the bend. Suddenly a dog appeared. Skinny. Brown. Then a teenage boy, wearing a jacket over a Pendleton flannel. He froze in his tracks. I walked toward him.

Are you from the crash? he said.

It was weird that he knew, I thought. Yes, I said.

Is there anybody else up there?

Yes. My dad and his girlfriend Sandra. The pilot’s dead.

What about your dad?

Before I could stop it, it spilled out of me.

Dead or just knocked out, I said. I shook him but he didn’t wake up.

The teenager stared at me. His stunned expression and my saying dead out loud unleashed the bleakness of it all—my dad is gone forever. He will never again wake me for hockey practice, never again lure me into a wave, never again point out the beauty in some storm. Pain attacked my bones, brittle and cold and easy to crush. An unbearable weight mounted on my back and my legs and feet trembled and I couldn’t look at the teenager’s sad face anymore. He was living proof that it was all real, that Dad was dead.

I looked at the ground and my spine strained to keep me from collapsing.

Should I carry you? he said.

No I’m fine, I said.

He picked me up anyway and I didn’t resist. He laid me across his outstretched arms. They felt like knives and the pain shot through my body and spiked through my head and it hurt so bad that I contorted—mind and body buckling into a pretzel.

As he carried me down the road I stared back at the mountain. Although it was smothered in boils of cloud, I knew vividly what was inside that storm, and for an instant the whole arc of my life was clear to me: Dad coaxing me past boundaries of comfort, day after day, molding me into his little masterpiece, even Nick’s vile fingers of doubt that I was left to fight alone, it was all completely transformed. Every misadventure, every struggle, everything that had pissed me off and made me curse Dad sometimes, rippled together, one scene tripping the next, the pieces speeding forward like falling dominoes into a streak.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу