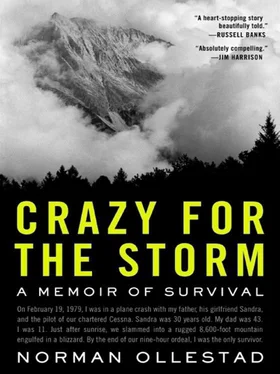

As I hobbled down the fan of snow, my mind flickered with muddled images that burned under a Mexican sun. No emotion, just faint smeared orange and yellow colors—Me, Grandpa, Dad, swimming in an ocean as warm as a bathtub.

My eyes were closed when the crust broke wide open. I danced my weight to my other foot and it caved too. I jiggered laterally and my magic ran out. I plummeted, knifing deep into the buckthorn. When I settled I was nearly entombed, only my head and one hand branching out of the snow.

I spit to clear snow from my mouth. I reached up with my free arm and the surface collapsed into my hole. My sneakers checked against the tangle of vines and I dropped a few inches deeper.

It’s like a tree well, I thought. I pictured my dad wedging his feet and arms against the sides and working his way up and out. I can do the same.

The vines gave way the instant I loaded against them. I willed my body upward and the limbs bent, worthless.

Some serrated leaves were still attached to the vine and when I moved again my ski pants and sweater pulled against the whole gnarl, quaking the snow around me.

Nothing was working, and nothing seemed like it would work. I was at the end of my tether. There was a flare of anger and frustration, abruptly smothered out, as if all the circuits in my brain were fizzling, and I shut down.

MY DAD WAS in the bleachers at the beginning of the second period like he promised. He had taken Sandra home because she had refused to sit in the cold ice rink. Right off the drop I ended up with the puck and split the defense with a burst of speed up the middle. There was no one to pass it to and the goalie charged out of his crease and kept coming so I stick-handled left, tucked the puck in and reversed direction. The goalie’s body was going the wrong way and I slid the puck under his outstretched glove.

Nice move, Ollestad, my dad called from the bleachers.

My teammates gave me high fives and the coach kept me on the ice. By the end of the second period I had an assist to go along with my goal.

After the game some of the kids on the other team complimented my play and I went to bed that night feeling like I was on a good roll. I really am all those things Dad keeps saying I am. Good enough to beat the bigger, stronger kids. Tougher than tiger shit—maybe even tiger piss. And tomorrow I will have a championship trophy to prove it.

IWAS PHYSICALLY AND mentally parched, stuck in a hole, tangled in indomitable vines and semi-unconscious. Like something pushing through a thick jungle, I became aware of myself again. A vague idea rustled me—a few feet away was something to grab, a hedge. I began to see my surroundings again—the backside of the massive ridgeline was a crown of rock jutting forward like a ragged ship prow. I’m close, close to the meadow, I reminded myself. I could use my fingernails, lunge—I ran through strategies. In spite of these whispered calls to action I didn’t actually move.

I heard a noise overhead. I looked up and saw a big airplane belly. The fog had completely given way to a heavy graphite-colored sky. The plane banked and I used my free hand to wave at it. I kept my eyes glued to it.

Miraculously it circled around. I waved and watched it come back over the meadow again. I waved and yelled. They can see me. I’m saved. Then it sailed over the ridge. They saw me. That’s why they circled.

I waited for a long time and the plane did not come back and no one came to save me or called out for me. The wind sounded like voices and I yelled, but only the wind answered.

The graphite sky was edged in black—night was creeping in, maybe an hour away. I felt depleted again, woozy, bleary-eyed. I figured that my struggle was over and that I was going to die.

DAD WOKE ME at 5:30 in the morning. Sandra was in the living room warming her hands over the potbelly stove. It took me a moment to remember why we were all up so early—the plane ride back to Big Bear.

As I laced up my Vans I noticed a couple of new photographs on the judge’s desk that was given to my dad by a penniless client as payment for keeping his son out of jail. Next to the old black-and-white photo of me harnessed to my dad’s back as he surfed a two-footer off the point was a color photo of Dad, Grandpa, and me swimming that day we arrived in Vallarta, our three heads poking out of the water like sea lions. Beside that was another one of Dad and me skiing in St. Anton, Austria—boot-deep powder—in which I’m leading the way with my deadly snowplow that could cut through anything , as my dad liked to say.

Who took the picture of us skiing in St. Anton? I said.

He came out of the bathroom naked, brushing his teeth.

I had a professional do it. Pretty nifty, huh?

It’s great. We’re both shredding.

Sandra walked over.

I wonder how big the trophy’s going to be, she said.

Should be pretty big. Right? I said.

Who cares about a trophy , said my dad. You know you won—that’s all that matters.

IWAS TRAPPED, WORN OUT and frozen. Night moved down on me like a mass of crows swooping in from all sides of the sky. I closed my eyes against them—wanting to fall asleep before they ate me.

Something like a jiggle wormed its way inside me. Something bigger, from the core of the earth, was counting out time. A drop of dew jiggling on a leaf, that faint.

I sensed the wind whistling through the gullies and heard it cut across the snow. Ice peppered my face. It dawned on me that I was still stuck and still cold and therefore still alive. I watched another gust peel off a skin of snow like grains of sandpaper ripping free. It made me think of a barren graveyard in a ghost town. I conjured my dad and me in Bodie, the cool dusk chasing us to the car, Dad saying the temperature had dipped from three-king cold to four-king cold, giving me license to say, That’s four-king A right.

I looked at the buckthorn rising out of the snow several yards away. I kicked at the buckthorn entwined with my legs and torso under the snow. No way to get to that first hedge.

Even so I stretched one arm toward the first hedge and my body floated in that direction. The snow caved and I circled my weight in ten different directions at once—a slow-motion dog paddle, treading water in the sea of vines. Intuitively my armpit, some ribs and a hip found a place to caress the vines and I delicately leaned, settling.

Like a gymnast swinging his legs over the horse, I lifted onto a ball of vines that buoyed against my hip. My feet then pushed off and I rose out of the hole. I was careful not to let my upper body reach too far across the snow and risk plunging headfirst into the next quadrant of mesh.

Then the vines collapsed. I pitched my hip under me and drove my legs downward, spreading all limbs, catching like a thorny lobe in dog hair.

Again I ventured one arm out. The snow felt solid before me. I spread my legs out in the mesh, dispersing the load. Under my forearm the crust was firm. I slithered chin, chest, then stomach onto this atoll. It cracked and I rolled onto my back. As the pane shattered I wheeled my feet and drove them down, ensuring they went first with the rupturing snow into the gnarl below. Sprawling wide again to ensnare the buckthorn, my head bobbled out of the hovel. There was the hedge. A leap away.

I lunged at it. Unfortunately I had no leverage and ended up sinking deeper into my pit. I tried again. Broadening my load this time, I uncoiled gracefully as I stretched one arm out. I eased over the lip of the pit. My fingers tickled the underside of the hedge. A little wiggle and my torso followed my arm out of the hole. I skated for an instant across the crust, then grabbed a throng of vines. My lame dexterity was salvaged by the tight weave of vines clasping me as much as I clasped them.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу