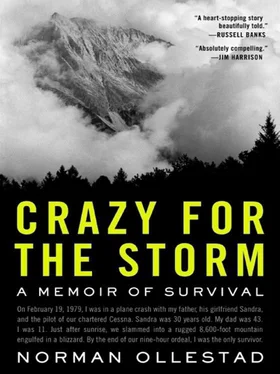

WE LEFT TOPANGA Sunday morning at 5:00 a.m., headed for the championship race. My dad and I wore Levis and T-shirts, and Sandra had on a parka. I cramped in the back of the Porsche on top of my hockey bag with my sticks on the floor—ready for my game that night after the ski race. My dad and I sang country songs all the way to Big Bear while Sandra slept on her pillow against the passenger window.

It was a clear day. The sun came up right over the Snow Summit ski resort, edging a pink halo behind the yellowish rotting snow. I had breakfast with the Mountain High ski team and realized during breakfast that I was racing for Mountain High today. When I asked my dad why, he said that in order to race in the Southern California Championships I had to be on a Southern California team, not the Incline team—even though I was from farther south than anyone else racing. My dad had arranged all this and in his typical fashion slid me into a whole new world as if it were just a minor detail. Without a fuss, without resentment, I reframed the situation, like Dad always seemed to do. Just a new name, the rest is the same: same gear, same mountain, same skis, same race. Looking at it like that was sure a lot easier than fighting it. At the end of breakfast Dad presented me with a fancy new Spyder race sweater to complete the transformation.

The snow had turned to solid ice over the last few days. By noon it would soften and my dad hoped they got the race going right away so that my second run wouldn’t be in the slush. The course was set much like Squaw Valley—steep and tight.

At 9:30 I took my first run. My line was too aggressive, a bit cocky, and I had to gouge the ice to make up for my poor angles. Still I was tied for first place with Lance, who was racing for Big Bear.

When the girls took their first run the sun was high and the snow was getting soft. Dad said there was a fast-moving shot of moisture coming in off the ocean, which was only eighty miles away. And by the time the girls were done I felt spindles of cool air wafting over the ridges and saw wispy clouds.

Come on baby, said my dad up at the clouds. Keep it cool for us.

After lunch ruffled blankets of cumulus striped the sky and the cool breeze was steady, keeping the snow hard enough to be to my advantage.

Let it all hang out, Ollestad, said my dad.

Come in high. Nice smooth turns, Norman, said the Mountain High coach.

Racer ready, called the starter, who then began the countdown. I adjusted my goggles under the rim of my helmet. A deluge hit my bladder and I pinched my thighs together, catching it in time. I cocked my wrists, guiding my pole tips over the wand and into the holes, arms stretched forward like Superman in flight.

Two…one…Go! said the starter.

My chest shot out between my hands and I drove my poles downward as my heels kicked back, rocking me onto my toes. My whole body launched off the pad before my boots tripped the wand. I came in high on the first gate. I brushed the gate and sliced up under it setting up my next turn. As the hill got steeper the ruts got deeper. My skis bent, uncoiling as I came out of the pockets, flinging me into the air. So I pulled my knees in on the next turn and felt my skis suck up the rut. One more gate to go, then the flush. I was well ahead of the turns and charged into the flush. Five quick edge changes—five quick turns through this tight section of gates. Slithering out of the flush the next rut bent 90 degrees, and when I hit it my kneecaps rammed my chin. Stars and the taste of blood. I was late into the next turn. Half blind, I chiseled my edges into the ice and abruptly released them, bouncing off the rut floor and into the air, losing some time in the process. When my skis touched down I set them on the proper line and spit out the blood before compressing into the next rut. Spit, compress, pivot the weight. Another jagged trough. Delicate edge work. Light as a cat. I found my way back into a good rhythm.

When I came through the finish line I choked on the blood. I coughed it up and spit onto the snow. My dad skied beside me. I looked up and his insatiable grin said it all.

Am I in first? I said to make sure.

Yep. Two more racers, he said. You okay?

I nodded. Lance’s coming now, I said, pointing up the hill.

He whizzed through the flush and ka-banged into that gorge of a rut and was thrown back onto the tails of his skis—never regaining control all the way to the finish line. My dad and I swung around to the board. My combined time was faster.

The next racer hit the first rut on the top and I saw him flip over. D.Q.

My dad nodded. Looked down at me. His face was placid. His smile was gentle.

You won, Ollestad.

I raised my arms and spit more blood. We stared at each other. I saw him so clearly. The cranium shelf rising off his forehead bumpy and uneven, the cluster of diamonds in the blue of his eyes fragile cracked windows, and I saw someone younger and full of grand ambitions and I thought about how he had wanted to be a professional baseball player. He looked at me as if into a mirror, studying me, like I was holding something that he admired, even desired.

Way to kick ass, he said.

Thanks, I said.

The Mountain High coach skated over and patted me on the butt.

Good skiing, he said.

He looked at me intensely too. It felt like there was a small fire in my cupped hands and everybody wanted to savor its heat.

Finally, I said.

ITURNED AWAY FROM Sandra’s body, shielded by twigs, and surveyed the landscape. From the crash site I had mapped out this elliptical apron and the tight gulch below it. I had to control my descent down the apron and, hopefully, forge that gulch, then I would find the meadow and, below somewhere in the woods, the road that would lead me to shelter.

As far as I could see the apron was perfect for my energy-saving technique of sliding on my butt. Off I went. After a few minutes I realized that I was turning around markings in the snow—rock tips, bumps, animal tracks, anything—and that I was whooping as if it was a slalom course. This playful whim struck me as careless so I stopped whooping, went straight, only turning to control my speed.

Nearly a thousand feet later the slope tapered into the gulch and the sides of the gulch rose like two tidal waves of rock about to slam together. I was deep in its heart. The pitch got steeper and I alternated between skimming on my ass and flopping onto my stomach to cleat the snow with my sticks.

As I descended, the terrain mutated into uneven rock mixed with snow, and the pitch tilted close to 35 degrees. It was too dangerous now. I had to stay on my belly.

Slowing down gave the gathering night a chance to overtake me. Each methodical step and fingerhold over the broken ground became a chore. Soon both sides pinched so tight I was forced toward the creek bed. I had sensed it down there in the crevice and wanted to avoid it at all cost. Getting wet would surely slow me down. Might give me hypothermia.

I noticed shrubs squeezing from the rock and decided it was worth taxing my strength to get to them. I used cracks in the rock, wedging my frozen fingers into them to traverse the dicey overhang above the creek. I got hold of the shrubs and lowered myself as close to the creek’s edge as possible. I was short by about two feet.

I eyed the transparent layer of ice coating the slurry of water that flashed beneath like schools of silver fish. Recalling how my dad almost froze when he had gotten wet during one of our backcountry powder adventures, I knew I had to stick the landing. Fall sideways, not backward, if you lose balance, I told myself.

Lowering my body, my hands slithered down the vine and I dropped. My feet plunged into the snow and I teetered backward. I forced myself to one side, landing on my hip, avoiding the creek. The buried foot did not release and I felt my knee tweak. I got up on my hands to relieve my knee. I pulled my feet out and started moving. The knee hurt but it worked.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу