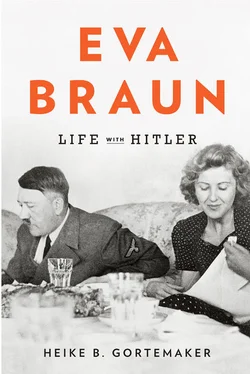

The realities of women’s lives in the National Socialist state were increasingly studied as a topic of historical research only from the late 1970s on. Until then, scholars of National Socialism concentrated primarily on analyzing the structures of power and thus women, who were excluded from important political, economic, and military roles in the Nazi state, were typically seen as insignificant and their influence was little examined. This approach was likewise—in fact, above all—to be found in the biographical portraits of the leading National Socialists—Hitler, Speer, Himmler. The journalist Gitta Sereny was an exception: for her biography of Speer, she also made sure to talk with Speer’s wife, Margarete, who had, after all, “for years seen Hitler as a private man day after day” and, Sereny believed, could hardly have “remained in total ignorance” of the Nazi crimes. 10Joachim Fest, on the other hand, as late as the early 1990s, maintained that the cult of Hitler among his early female supporters from the “better circles of society” (for example, Helene Bechstein, Elsa Bruckmann, and Viktoria von Dirksen) had its cause in the “exuberance of feeling among a certain type of older woman, who sought to awaken the unsatisfied drives inside them in the frenzy of nighttime mass rallies around the ecstatic figure of Hitler.” There is no talk of these women having any possible political motives or well-thought-out antidemocratic or anti-Semitic positions, though Fest does discuss their moral decay, world-weariness, “muffled covetousness,” and a “maternal concern” projected onto Hitler. 11

The memoir literature by Hitler’s more or less close collaborators, which seeks to explain his mass popularity, encourages such interpretations. Moreover, in such texts the wives, girlfriends, and female family members are usually on the margins, mentioned only as passive bystanders. “Eva Braun had no interest in politics,” wrote Albert Speer, for example. “She scarcely ever attempted to influence Hitler.” Speer likewise claimed about his own wife that she was “not political.” In general, he almost entirely excludes his family from his postwar reminiscences, in which, as his youngest daughter complained, his wife and children are “practically nonexistent.” 12The women’s own writings, in turn, retrospectively give the impression that these women were occupied exclusively in the private sphere during the twelve years of Nazi rule, casting the authors as devoted but politically passive companions to their men. They deny any personal responsibility or guilt, since they were, they say, to a large extent unaware of what was going on around them. Margarete Speer, for example, kept silent her whole life about her role in the Berghof inner circle as well as about her relations with Eva Braun and Anni Brandt (the wife of Hitler’s attending physician, Karl Brandt), and was thus described by her children “as always completely apolitical.” 13Maria von Below’s husband, Nicolaus von Below, worked in Hitler’s immediate surroundings as air force adjutant from 1937 to 1945 and developed an increasingly close “relationship of mutual trust” with him over the course of those years; she later said that at the time, when she belonged to the circle of women on the Obersalzberg, she had been “not all that pleased to come into that political world”—she and her husband were, she said, “entirely apolitical.” 14

In fact, most women claimed after the war that they had had nothing to do with politics in the years before 1945. The widespread claim of “feminine innocence” was, not least, part of the strategy of exoneration in a debate about the past that took place in Germany in the 1950s. Even decades later, the psychoanalyst Margarete Mitscherlich reaffirmed, in a much-noticed book called The Peaceable Sex , that anti-Semitism is intrinsically masculine—a “social disease” that stands in close relation to “typical male development.” Women, on the other hand, are inclined to conform to “male prejudices” out of a “fear of loss of love.” In the Nazi period, she writes, women, “like all weak and oppressed members of a society,” thus identified with the “aggressor.” 15To this day, the fact that a woman like Eva Braun did not take part in any of “the decisions that led to the worst crimes of the century” is taken as proof of her exclusively private existence, “outside of history.” 16But is uncritically sharing Hitler’s worldview and political opinions not enough to transform someone from a victim into a collaborator? Doesn’t the danger of a dictatorship consist precisely in such blind obedience?

It has thus become more and more common to no longer see the wives of Nazi Party leaders or functionaries as mere dependents or conformists, but to understand them as active agents, “complicit” or even “perpetrators” in their own right. This new perspective has already led to studies centered on female propagandists of the NSDAP, or on women who were active in the SS system. But it also illuminates the hitherto unnoticed lives of SS men’s wives, and their significance for the SS “clan-community.” The conclusions were as could have been predicted: these women actively or passively consented to the “murderous reality” surrounding them every day, and at the very least lacked a sense of guilt. It was apparently socially acceptable “normal behavior” to support criminal activity. 17

Despite the paucity of sources, Eva Braun’s case, too, and that of the other women belonging to the closed community at the Berghof, must be investigated—and her concrete everyday life and behavior in the Nazi regime reconstructed—without letting our view of the facts be obstructed by the image of women in Nazi propaganda, later strategies of self-justification, or the myth of “male power” in the Nazi regime. 18In the final analysis, the only way to understand Eva Braun’s status and social function within Hitler’s private environment, and her significance in the Berghof group, is to answer the question, What were her own motives? Until now, though, no one has seemed to suppose that she pursued any goals of her own whatsoever. The technicality that she was never a member of the NSDAP or any other Party organization has been taken as proof of her allegedly apolitical behavior; Eva Braun exists in the public eye, even today, only as a submissive victim or as someone who enjoyed the fruits of male actions without participating in them. But to what extent did she herself identify with the National Socialist state? Within the limits drawn for her as a woman and as Hitler’s secret mistress, was there any room to maneuver that she actively made use of? Albert Speer, in an interview with Gitta Sereny a few years before his death, claimed that Eva Braun had been “helpful to many people behind the scenes” without ever making this known. 19How we should take Speer’s brief mention of these activities remains to be seen, but it is clear that they do not fit the common picture of an entirely unaware and uninterested mistress.

The lives of the Nazi elite’s wives and lovers, kept hidden from the public, developed along lines that often contradicted the publicly proclaimed principles of the regime. For example, the diplomat and travel writer Hans-Otto Meissner criticized the “founder of National Socialism” in his postwar memoir for having disregarded “the principles of the Third Reich” at his formal events. Meissner was the son of Otto Meissner, who for many years was head of the Office of the Reich President, which in 1934 became the Presidential Chancellery of the Führer, and he grew up in the Reich President’s official residence on Wilhelmstrasse. He wrote that the “official representations at the Berlin Reich Chancellery,” including state ceremonies and festivities, were constantly violating Party rules; in fact, they were diametrically opposed to the behavior that Party functionaries were advocating “in the whole Reich.” Meissner was intimately familiar with how the Nazi regime conducted itself on the international stage, both because he worked in the German diplomatic service in London and Tokyo from 1935 to 1939 and because his father, as the “Chief of the Presidential Chancellery of the Führer and Chancellor,” was almost solely responsible for managing large, formal events. He remarked that at the state dinners Hitler held in Berlin, not only was the reactionary “kiss of the hand” in good form, but participants also enjoyed the “foreign luxury products,” such as “old Burgundy” and “French champagne,” that were consistently demonized in Nazi propaganda. 20And even while the NSDAP especially targeted female cigarette consumers in their nationwide antismoking campaigns—posting in restaurants and cafés placards that said “The German Woman Does Not Smoke!”—in the Reich Chancellery “liveried servants” offered “the ladies Egyptian cigarettes,” according to Meissner. The “ladies at the Führer’s table,” the former diplomat revealed to his countrymen in 1951, wore evening dresses from “Lanvin and Patou” and wreathed themselves “in Chanel and Chypre perfumes.” 21

Читать дальше