The first meeting of Hitler’s cabinet took place at 5:00 p.m. the same day. At around 8:30, Hitler showed himself at the window to his followers, who—in an improvised mobilization from Goebbels—marched from the Grosser Stern in the Tiergarten, through the Brandenburg Gate, to Wilhelmstrasse in a torchlit procession that included thousands of Berliners. 69Although the conferring of power upon the head of the NSDAP was in no way seen as a turning point at the time, the leading National Socialists immediately created the legend of a “German revolution,” and they conducted themselves like bellicose upstarts. Intoxicated by their success, they did not leave the Chancellery until the early morning hours of January 31. 70

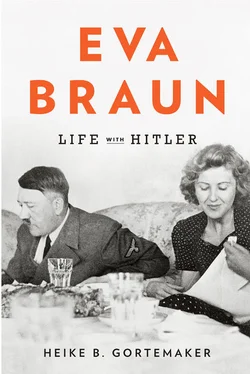

Hindenburg, who had temporarily been using the official residence in the Chancellery since October 1932, apparently saluted the masses marching past his window until after midnight. Gathered around Hitler were his vice-chancellor, Franz von Papen, Wilhelm Frick, and Hermann Göring as minister without portfolio and acting head of the Prussian interior ministry, as well as Joseph Goebbels, Rudolf Hess, NSDAP lawyer Hans Frank, Heinrich Hoffmann, and other followers. As the night progressed, Hitler managed to withdraw to a small room next to the chancellor’s ballroom and reception hall, where he held forth in a monologue for hours on end before his comrades-in-arms. 71A large number of phone calls and telegrams had already arrived from Germany and abroad, acknowledging the change of government, to the point that the telephone lines were sometimes jammed. Nevertheless, Hitler, it is said, tried to reach Eva Braun by phone in Munich that night. 72

Eva Braun did not actually have her own phone. In the early 1930s, a telephone was a luxury item that only a few private households could afford, especially in a time of general economic hardship. Long conversations on the telephone were still rare; in general, the phone was used for brief communications or to call for help in emergencies. There were, however, already some four hundred thousand connections in the metropolis of Berlin, population four million. The German postal service was just beginning to promote the purchase of telephone connections, with a brochure called “You Need a Telephone Too.” 73In any case, Hitler could reach Eva Braun by phone only at the office of his friend Hoffmann. She apparently spent nights at the office, sleeping on a “bench” and waiting for her lover’s phone call. 74Only after Hitler was introduced to Braun’s best friend Herta Ostermayr at Café Heck in Munich, which was after he had come to power, did he “always” call the Ostermayrs “from Berlin”—as Herta later recalled—“since the Brauns didn’t have a phone.” 75This arrangement did not last long, though—the official phone book of May 1, 1934, lists Eva Braun with her own phone number at 93 Hohenzollernstrasse. Even though the address was that of her parents’ apartment, the name in the phone book was hers alone, 76which shows that the phone line was acquired especially for her, so that she could talk on the phone with Hitler undisturbed.

On January 30, 1933, there was no such possibility. If we are to believe Nerin E. Gun, it was a nun collecting donations from the Brauns on the afternoon of January 30 who told Eva the news from Berlin. Eva Braun’s first reaction was happiness; then, in the following days at Photohaus Hoffmann, she enthusiastically collected photographs of the National Socialist rally in Berlin while her father and her sister Ilse expressed reservations about the change in government. According to Gun, Franziska and Ilse Braun, who lived together in the family home in Ruhpolding in Upper Bavaria after Friedrich Braun’s death on January 22, 1964, stated that Eva Braun grew very pensive after her initial reaction of high spirits, because she was afraid that she would be able to see Hitler even less often than before. 77

PART TWO

Contrasting Worlds

5. WOMEN IN NATIONAL SOCIALISM

National Socialist propaganda put forth an official image of women that implied a single standard model for women’s lives. Countless brochures, textbooks, proclamations, and speeches constructed the ideal of a woman’s world completely restricted to the domestic and social realms. In a speech before the National Socialist Women’s League at the NSDAP convention in Nuremberg on September 8, 1934, for example, Adolf Hitler explained: “If we say that the world of the man is the state, the world of the man is his struggle, his readiness for battle in the service of the community, then we might perhaps say that the world of the woman is a smaller world. For her world is her husband, her family, her children, and her house.” 1As the speech continued, Hitler referred to “nature,” “God,” and the “Providence” that had “assigned women to their ownmost world” and made them, in this clearly demarcated realm, “man’s helper” and his “most faithful friend” and “partner.” 2

The “Reich Women’s Leader” Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, only thirty-two years old at the time, spoke to the members of her sex at the same event. Although she was to push for the Gleichschaltung [5] Translator’s note: Sometimes translated as “coordination” or “integration,” this term refers to the nationalization under National Socialism of previously private or independent organizations.

of the women’s unions and the establishment of a women’s labor service in the coming years, she implored the women in her audience to become a part of the People—and part of History—by “being a mother.” At the same time, though, she also appealed to women working in industry or farming, by declaring: “Clear the path from yourself to other women, and never let your first question be what National Socialism brings us, but rather ask first, and over and over again: What are we prepared to bring to National Socialism?” 3Clearly the “Reich Women’s Leader”—unlike Hitler himself—was concerned not to exclude working women, who numbered more than a million by that point, but instead to integrate them, as well as housewives, into the Nazi “Volksgemeinschaft.” [6] Translator’s note: The “Volksgemeinschaft” was the Nazi social ideal of a racially unified and hierarchically organized “People’s community.”

4

In actual fact, the image that Hitler and the Nazi propagandists presented of the lives of women and girls in Germany had little to do with reality. In 1932, during the worst phase of the economic depression in Germany, a higher percentage of women than men were fully employed. 5After Hitler came to power, the number of women in industry rose steadily from 1,205,000 in 1933 to 1,846,000 in 1938. 6The actual lives of women in the “Third Reich” beyond the “cult of the mother” was thus significantly more multilayered and complex than is generally assumed.

There were, however, many professions that women were no longer allowed to practice after 1933. Hitler had personally forbidden women from being licensed as judges or lawyers in the German Reich, and decided that “women were categorically not to be used as high government officials.” Exceptions would be made only “for positions especially suited to women, in the areas of social work, education, and health services.” 7At the Party convention in 1936, Hitler declared once again to “all the literary know-it-alls and equal-rights philosophizers” that there were “two worlds in the life of a People: the world of the woman and the world of the man.” 8However, economic constraints such as the shortage of labor in the country, as well as Nazi political goals including the rearmament program under way since 1936 and the concomitant need for workers, made it harder to carry out a unified ideological political program for women and families based on racist/biologist principles. 9

Читать дальше