Hoffmann’s son-in-law, Baldur von Schirach, has left a more plausible account, which also gives a precise date for the incident—despite the fact that he must have heard about what happened from Hoffmann or Dr. Plate. He says that Eva Braun’s first suicide attempt took place on the night of August 10–11, 1932. According to Schirach, Hitler received a farewell note from Eva Braun on the morning of August 11—shortly before his planned departure from the Obersalzberg to Berlin—and immediately postponed the trip. That evening, he met with Dr. Plate in Hoffmann’s Munich apartment, where Plate told him about Braun’s injuries and Hitler said to Hoffmann that he wanted to take care of “the poor child.” Only on the following day, Friday, August 12, did he finally leave for Berlin. 37

These statements agree with Goebbels’s notes. Under the date of August 11/12, Goebbels wrote that Hitler was on the Obersalzberg early on the morning of August 11, and that Hitler and he traveled together to a meeting in Prien on the Chiemsee (a lake nearby). “In the afternoon,” the two men continued to Munich, where Hitler went to his apartment on Prinzregentenplatz; while Goebbels took the night train to Berlin, Hitler stayed in Munich. “The Führer,” Goebbels noted, “will come later by car.” They met up again only at 10 p.m. on August 12, in Caputh, to discuss the Nazi leader’s upcoming meeting with President Hindenburg. 38

A third, completely different version is Nerin E. Gun’s, for which he gives Ilse Braun as the source. This version dates the suicide attempt to the night of November 1–2, 1932. On that night, says Ilse Braun according to Gun, she found her sister Eva by chance, alone in her cold, unheated apartment, covered in blood, on the bed in their parents’ bedroom, while their parents were away on a trip. Despite her injury, Eva Braun was conscious and had herself called a doctor to take her to the hospital. “The bullet had lodged just near the neck artery,” in Ilse Braun’s exact words according to Gun, “and the doctor had no difficulty in extracting it. Eva had taken my father’s 6.35 mm caliber pistol, which he normally kept in the bedside table beside him.” 39In this account, it is unclear (to say the least) where Eva Braun could have telephoned from; the date in early November is also significantly different from Hoffmann’s and Schirach’s accounts. Nevertheless, the events could indeed have played out like this, as we can see from a closer examination of Hitler’s schedule.

The Nazi leader was in the middle of an exhausting campaign trip at the time, and undertaking his fourth “Germany flight” between October 11 and November 5. The Reichstag elections of July 1932 had not solved the problem of the Weimar Republic’s inability to govern, but only led to a further weakening of the forces of democracy in the parliament, so that Hindenburg’s Chancellor, Franz von Papen, was defeated by the second sitting of the newly elected Reichstag, on September 12. The Communist Party’s motion of no confidence, supported by the NSDAP and all the other major parties, had toppled the government. The Reichstag was thus dissolved, for the second time in the space of a year; the requisite new elections were called for November 6. Now it was up to the National Socialists and their “Führer” to mobilize the masses even more forcefully and finally emerge from the election as the absolute victors. 40

On the evening of November 1, 1932, after giving election speeches that day in Pirmasens and Karlsruhe, Hitler first flew back to Berlin, where he was to speak at a large rally in the sports stadium on the following evening. 41He would have heard about the incident in Munich that same night, and left the capital in the early morning hours of November 2. 42Goebbels was at a rally that night in Schönebeck, south of Magdeburg, until 1 a.m., and arrived in Berlin at around 4 a.m.; he noted curtly in his diary: “To Berlin…. 4 a.m. arrival. Hitler just gone.” 43Together with Hoffmann and an adjutant, according to Gun, Hitler was chauffeured to Munich so that he could visit Eva Braun in the hospital on the morning of November 2. Hoffmann accompanied Hitler to the hospital, where he expressed doubt about the seriousness of Braun’s suicide attempt in the presence of the attending physician. After the physician explained that Braun had “aimed at her heart,” Hitler is said to have remarked to Hoffmann: “Now I must look after her,” because something like this “mustn’t happen again.” 44

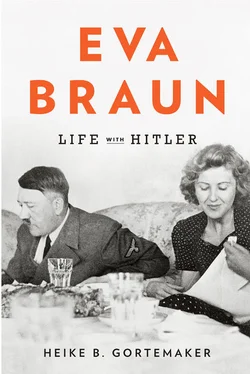

Although the precise details remain unknown, witnesses and historians agree that Eva Braun felt abandoned and calculatedly acted to make the perpetually absent Hitler notice her, and to tie him more closely to her. 45She is said to have intentionally summoned Hoffmann’s brother-in-law, Dr. Plate, rather than her sister’s friend, Dr. Marx, to ensure that Hitler would immediately hear about the incident from his personal photographer. 46In truth, only a year after Hitler’s stepniece Geli Raubal’s suicide and in the middle of his political battle for the chancellorship, whose success was closely bound up with the “Führer cult” around him, the NSDAP could not afford a new scandal that opened up Hitler’s personal life to public discussion once more. He thus had to bring under control a relationship he had apparently misjudged. From then on, in this version of events, a tight bond grew out of the hitherto rather loose relationship with Eva Braun. Heinrich Hoffmann wrote after the war that Hitler told him then that he “realized from the incident that the girl really loved him,” and that he “felt a moral obligation to care for her.” 47About his own feelings, in contrast, it seems that the “Führer” had nothing to say.

Alone in the Vestibule of Power

Meanwhile, only a few intimates knew about Hitler’s relationship with Braun, now twenty years old. Hitler himself had erected a “wall of silence” around her. They made no joint public appearances: only once in the twelve years after 1933 were Hitler and Eva Braun seen together in a published news photo, which in fact shows Eva Braun sitting in the second row, behind Hitler, at the Winter Olympics in February 1936 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. 48Nothing in the picture indicates any personal relationship between her and the dictator. Officially, Eva Braun was on the staff of the Berghof as a private secretary. 49The German public learned only shortly before the end of the war that Hitler had lived with a woman and eventually married her, and many people at the time considered this report a mere “latrine rumor.” 50

In Hitler’s more immediate environment, on the other hand—among his close colleagues in the Party and their wives, and adjutants and staff members—the relationship between their “Führer” and Eva Braun could not remain a secret. For example, on January 1, 1933, a Sunday evening only a few months after her attempted suicide, she accompanied Hitler to a performance at the Munich Royal Court and National Theater, together with Rudolf Hess and his wife, Ilse; Heinrich Hoffmann and his fiancée, Erna Gröbke; and Hitler’s adjutant Wilhelm Brückner and Brückner’s girlfriend Sofie Stork. Hans Knappertsbusch, the musical director of the Bavarian State Opera House, was directing Richard Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nuremberg . 51This opera had premiered on the same stage in 1868, and its performance on New Year’s Day 1933 launched the nationwide celebrations of Wagner on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of his death on February 13, 1883.

At the same time, only a few streets away from Max-Joseph-Platz and this nationalistic drama about the life and work of the early-modern minnesingers, twenty-seven-year-old Erika Mann was celebrating the premiere of her politico-literary cabaret, “The Peppermill,” in the Bonbonnière, a small, somewhat dilapidated stage near the Hofbräuhaus. 52Erika Mann, here lashing out in supremely entertaining and successful fashion at the main players in the dawning “new age,” was as hated in Munich’s nationalist circles as her father, Thomas Mann. And in fact, the same Hans Knappertsbusch, a prominent representative of Munich’s intellectual life, initiated a “Protest from Munich, the Richard Wagner City” against Thomas Mann, which was published in the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten three months later, in April 1933. The occasion was a lecture the writer gave in the purview of the Wagner celebrations at the university, with the title “The Sorrows and Greatness of Richard Wagner.” Knappertsbusch and more than forty cosigners resolutely rejected Mann’s alleged disparagement of Wagner. 53

Читать дальше