In the months immediately following Hitler’s Chancellorship, it was Goring, not Himmler, who was the principal activator of police control. He poured his prodigious energy into the defeat of the remnants of democracy in Germany and into the rout of the Communists, the Party’s chosen enemy in the Reichstag and in the streets. Speed was what mattered, and the use of violence and terror to break up the forces of resistance before they could realize what was happening and oppose this sudden, savage onslaught by rallying themselves to out-vote Hitler in the elections due on 5 March. Within a week the Prussian Parliament was dissolved; within a month unreliable police chiefs and civil servants alike were dismissed and replaced, and the police, both new and old, were armed; ‘a bullet fired from the barrel of a police pistol is my bullet’, cried Goring. To stop disorders, either real or imagined, Goring commandeered 25,000 men from the S.A. and 10,000 from the S.S. and armed them to supplement the activities of the police; the Communist leaders were arrested and their party virtually put out of action before the elections could be fought. In February, the night of the Reichstag fire, both Hitler and Goring declared that a Communist putsch had been imminent and that the fire was a beacon from heaven with which to blaze the trail of the Communist traitors. On 28 February the clauses of the constitution guaranteeing civil liberties were suspended, and anyone could be placed without trial under ‘protective custody’. At the polls the Nazis secured only a bare majority along with their allies the Nationalists, but with the Reichstag stripped of its Communist deputies Hitler was able to put through an Enabling Bill on 23 March which gave him power to govern by means of emergency decrees.

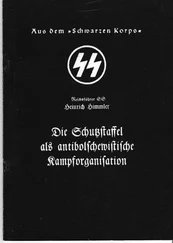

Action of this order was scarcely in Himmler’s nature. When it was decided that the Catholic Conservative government in Munich should be removed, it was the S.A. under the Ritter von Epp, the friend of Roehm, who dismissed them on 8 March. Himmler, the Bavarian President of Police, was by-passed. In the same month, Goring set up his first concentration camps in Prussia under the supervision of Diels, and in April segregated his political police in their own headquarters in the Prinz Albrechtstrasse in Berlin. In January they became known officially as the Geheime Staatspolizei, the Secret State Police, or Gestapo for short. This was a first significant move towards centralization in the police control of the state, and it was a warning to Himmler, whose autonomy still lay only in Bavaria.

Between April 1933 and April of the following year, Himmler took his own devious but independent line of action. Heydrich had become head of the Bavarian secret police and of the S.S. Security Office. Himmler established his own model concentration camp at Dachau, parallel with those created by Goring and others which were set up elsewhere, both semi-officially and unofficially by the S.S., the S.A. and the Nazi Gauleiters, who had been hurried into office in the various Gaue, or regions, into which Germany was divided for Nazi administration. At Nuremberg Goring claimed that he closed those unauthorized camps that came to his notice and where, he gathered, brutalities were practised. A camp founded by the S.S. near Osnabrück led to active friction between Himmler and Goring, whose investigators, led by Diels, claimed they were fired upon by the S.S. guards when they were sent to find out what was happening. Himmler was forced to close the camp on direct orders from Hitler. Göring’s intervention was largely dictated by his desire at this time to become the co-ordinator of police activities throughout Germany. That he failed was due to the persistent ambition of Himmler to improve his personal position and the desire of Roehm to merge the large forces of the S.A. into those of the regular army with himself as Supreme Commander, a situation which neither Goring nor Hitler would tolerate.

To control his camp at Dachau, Himmler established a volunteer formation of S.S. men willing to undertake long-term service as camp guards. This central formation was called the Death’s Head (Totenkopf) unit and granted the special insignia of the skull and crossbones; the officer put in command of this and other Death’s Head units was Theodor Eicke, a former Army officer and veteran of the First World War, who was one of Himmler’s most trusted adherents on racial matters. One of Eicke’s guards at Dachau was an Austrian, Adolf Eichmann; another in 1934 was Rudolf Hoess, later to take charge of extermination of the Jews at Auschwitz.

Hoess — another man, like Goebbels and Heydrich, at one time intended for the Catholic priesthood — had been a soldier during the 1914 — 18 war, and later joined the Free Corps. 14He had been involved in a brutal political murder and imprisoned for six years before becoming a Nazi after his release and joining the S.S. This extraordinary man, so dutiful and even intelligently moralizing in his attitude, wrote his memoirs in confinement after the Hitler war and explained in great detail his relations with Himmler. He had belonged to the idealistic agricultural organization called the Artamanen, a nationalist youth movement which was dedicated to the cultivation of the soil and the avoidance of city life. It was through this that he claims he first came to know Himmler, who, in June 1934 at an S.S. review in Stettin, invited him to join the staff in Dachau, where in December he held the rank of corporal in the Death’s Head Guards.

Dachau, Himmler’s experimental concentration camp, was established by an order signed by him as Police President of Munich on 21 March, and authorized by the Catholic supporter of the Nazis, Heinrich Held, the Prime Minister of Bavaria, a few days before his forcible expulsion by the S.A. The order, which appeared in the Munich Neueste Nachrichten on the day it was signed, read:

‘On Wednesday 22 March, the first concentration camp will be opened near Dachau. It will accommodate 5,000 prisoners. Planning on such a scale, we refused to be influenced by any petty objection, since we are convinced this will reassure all those who have regard for the nation and serve their interests.

Heinrich Himmler Acting Police President of the City of Munich’

Dachau, which was situated about twelve miles north-west of Munich, became a permanent centre of sanction by the Nazis against the German people and all those whom Hitler was later to subject. In the first unbridled period of power, the seizure of men and women for interrogation, often under torture, by the S.S. and the S.A. grew out of hand, and by Christmas 1933 Hitler found it necessary to announce an amnesty for 27,000 prisoners. No one now knows how many were in fact freed, and Himmler was later to boast that he succeeded in persuading Hitler to omit any prisoners in Dachau from the amnesty.

The order for protective custody was as brief as the order establishing Dachau; it read: ‘Based on Article I of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State of February 28 1933, you are taken into protective custody in the interest of public security and order. Reason: suspicion of activities inimical to the State.’

Goring was quite open about the reason for establishing the camps: ‘We had to deal ruthlessly with these enemies of the State… Thus the Concentration Camps were created to which we had to send first thousands of functionaries of the Communist and Social Democratic parties.’ Frick was later to define protective custody as ‘a coercive measure of the Secret State Police… in order to counter all aspirations of enemies of the people and the State.’ 15

Goring’s barbarous vigour was one aspect of Nazi cruelty; Himmler’s attention to the details of brutality was another. Almost twenty years separate us from the full exposure of what happened in the concentration camps, and no documentation could be more complete, ranging from the testimony given by thousands of persecuted men and women who managed to survive, to the detailed witness of such men as Hoess and Eichmann, Himmler’s agents in the most fearful record of torture, destruction and despair that human history has ever compiled in such thorough and horrifying detail. While Goring as a man was no more brutal than many other oppressors in the evolutionary struggle of modern Europe, the coldly punitive administration of sadism by Himmler challenges comprehension. Yet it is necessary to understand him, not least because there will always exist human beings who, once they are given a similar power over others and have similar convictions of superiority, may be tempted to act as he did.

Читать дальше