Himmler never became a member of Hitler’s more intimate social circle, certainly never in the sense that Goebbels or Goring rivalled each other in entertaining the leader, taking meals with him or accompanying him as confidential adviser on his missions. Hitler never stayed at Himmler’s house in Gmund, though he made occasional brief visits. Himmler, hiding his ambitions under a kind of obsequious devotion to service, accepted a lower level of influence during this crucial period in Hitler’s formidable onslaught on the succession of weak and crumbling governments in the Reichstag. It is true that he had become a Party deputy in the Reichstag in 1930, 9but unlike Goring or Goebbels, he took no prominent part in the acrimonious and violent exchanges which Goring largely engineered in order to bring discredit to the Reichstag as a machine of government. His part in the Reichstag was that of the supporter of policies determined by others, and a revealing glimpse of him has been recorded on the day when Goring, as President of the Reichstag, outmanoeuvred von Papen’s government and secured the dissolution of the Chamber. It was Himmler, resplendent in his black uniform, his pince-nez secure, who hurried from the Reichstag during the recess to fetch Hitler to a conference at Göring’s presidential palace. He beamed, he clicked his heels, he Heil-Hitlered, and he urged the Führer to hurry as they had Papen at a disadvantage. 10

A tenuous, but none the less important, link between Himmler and the Führer at this time lay in the financier Wilhelm Keppler, described by Papen at the Nuremberg Trial as ‘a man who was always in Hitler’s entourage’. By 1932 Keppler had become one of Hitler’s closest economic advisers; he had been introduced to Hitler by Himmler, and his gratitude expressed itself later in his financial patronage of Himmler’s racial researches. 11Keppler became one of the principal men responsible for maintaining relations between the Party and a widening circle of industrialists, and it was through him that the notorious meeting between Hitler and Papen took place at the house of the banker Kurt von Schroeder in Cologne, on 4 January 1933, when certain plans to bring down Schleicher’s government were discussed which were to result in Hitler becoming Chancellor at the end of the month. Himmler was a shadowy supporter on the occasion of this meeting, and later assisted in promoting the next stage of the negotiations through a newcomer to the political stage, Joachim von Ribbentrop, at whose villa in Dahlem the uneasy conferences were continued between Hitler and Papen with Keppler and Himmler still present.

Roehm, meanwhile, was taking an arbitrary line with the S.S. in Berlin, which under Daluege still managed to remain independent of Himmler in Munich. Roehm appointed his own director of training for the S.S. in his area, Friedrich Krueger, but on public occasions Roehm and Himmler appeared together in apparent harmony. Himmler was in no position to press openly for power; he was forced to play the part of the subordinate, while at the same time he studied the opportunities which the work of Heydrich and his S.D. agents were so diligently compiling. He was well satisfied with the rapid growth of the S.S. directly under his control, and with the carefully planned organization and training which had been achieved.

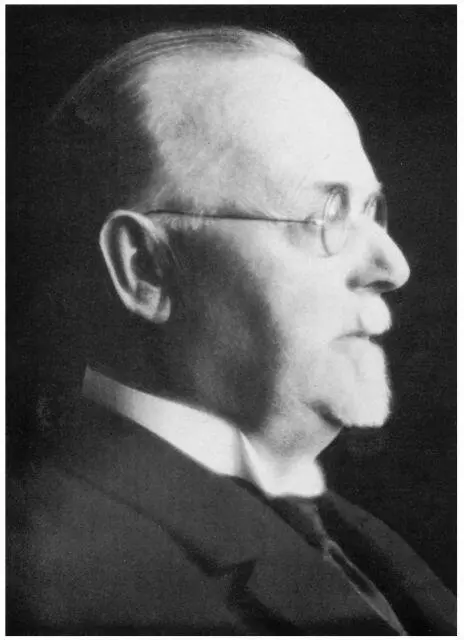

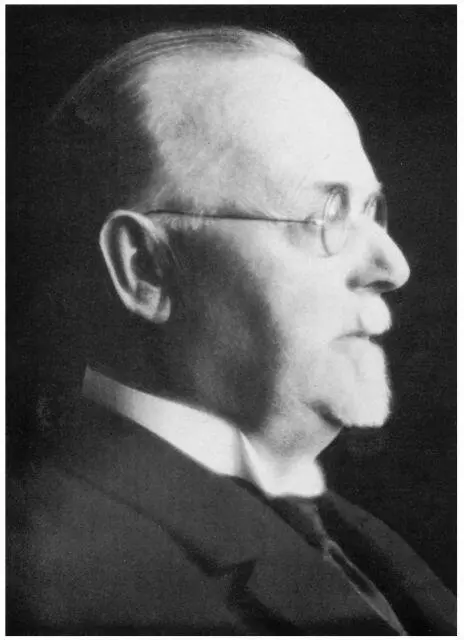

Himmler’s father, Gebhard Himmler

Himmler as a schoolboy in Munich (second row from the front, second from the right)

A description of the S.S. formations during the period 1933-4 was given before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg by von Eberstein, the man who had introduced Heydrich to Himmler; Eberstein was an ex-officer and civil servant who had joined the S.S. in 1928 and was typical of its aristocratic leanings. ‘Before 1933’, he said at Nuremberg, ‘a great number of aristocrats and members of German princely houses joined the S.S.’ 12He mentioned, for example, the Prince von Waldeck, and the Prince von Mecklenburg, and after 1932, the Prince Lippe-Biesterfeld, General Graf von Schulenburg, Archbishop Groeber of Freiburg, the Archbishop of Brunswick and the Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. When Himmler took over in 1929, there had been, according to Eberstein, only about fifty S.S. men in the district of Thuringia, where he was acting for the S.S. in Weimar, but after the seizure of power he had charge of some 15,000 S.S. men in the area covering Saxony and Thuringia. The elegant S.S. uniform attracted recruits and added to their social prestige. As Eberstein said at Nuremberg:

‘The increase can be explained first by the fact that the National Socialist government had come to power, and a large number of people wanted to show their loyalty to the new State. Secondly, after the Party in May 1933 ordered that no more members should be taken, many wanted to become members of the semi-military formations such as the S.S. and S.A., and through them to become members of the Party later. But then again there were also others who sought the pleasures of sport and the comradeship of young men and were less politically interested… From about February or March 1934, Himmler ordered an investigation of all those S.S. members who had joined in 1933, a thorough reinvestigation which lasted until 1935, and at that time about fifty to sixty thousand members throughout the entire Reich were released from the S.S…. The selection standards required a certificate of good conduct from the police. It was required that people be able to prove that they led a decent life and performed their duty in their profession. No unemployed persons or people who were unwilling to work were accepted.’

For Heydrich, the S.S. already represented the nucleus of a secret police once the Party came to power. As Reitlinger has pointed out, an official political police already existed in both Berlin and Munich, and when the great police purge came after 30 January many men in this secret service remained to serve the Nazis; among them for example was Heinrich Mueller, who later became head of the Gestapo before he had in fact become a Party member. Affidavits read at the Nuremberg Trial make it clear that the S.D. was well prepared with its screenings of the members of the Political Police in Munich, which was known as Department VI of the Police Organization. Most of them were immediately absorbed into the service of Himmler when he was appointed President of Police in Munich by Hitler, a very minor office compared with that given to Goring who, in addition to his Cabinet rank and Presidency of the Reichstag, became also Minister of the Interior for the state of Prussia. This appointment gave Goring charge of the police in what was by far the largest and most influential state administration in Germany. Goring immediately used his authority to place the Berlin S.S. leader, Kurt Daluege, at the head of the Prussian police, and appointed Rudolf Diels, a police official married to his cousin, Ilse Goring, as head of the section of political police that he created, the Berlin Police Bureau 1A, which was later to be renamed the Gestapo. Daluege at this stage was wholly under the influence of Goring and refused even to receive Heydrich, who went to Berlin to see him on Himmler’s behalf on 15 March. Daluege, young, bland and opportunist without either intelligence or conscience, had reached the rank of an S.S. general by the age of twenty-nine. Before joining the S.S., he had been in charge of refuse disposal for the City Engineer. Now he had to use his wits to steer his way through the conflicting currents of his superiors’ struggle for power. 13

Читать дальше