‘Give them your Cossack dance, Eugene,’ I called out.

And down he went on his haunches, kicking up the dust as we stamped out the rhythm. The children screeched with joy and the grown-ups came out to laugh and wonder at his cavorting.

Zaro’s uninhibited performance was like a derisive gesture towards the aloofness and dignity of the man who had just gone. And I think Zaro was not unaware of it.

In the fullness of time we came to a fork in the rough trail which we confidently accepted as that mentioned to us by the Circassian — the eastward branch leading to Lhasa and the other south-west to India. A few hours later we saw far off a big caravan of possibly fifty men and animals creeping slowly away from us in the direction we imagined to be Lhasa. It was the only large travelling group we ever saw in the country.

We found this to be a country not only of rugged ranges but also of great lakes. Near the end of November our way led us to a vast sheet of water like an inland sea. From the high ground as we came down to it we tried to guess its size. We thought we must be looking across the breadth of it and because we could not be sure that the thin line on the horizon really was the far shore, estimates of the distance varied from sixteen to forty kilometres. There was no way of even roughly calculating the length — we could not see either limit. We bathed in the fresh cold water and camped the night around a fire which did not throw out quite enough heat to keep out the damp night air from the lake.

Then followed a period of comparatively easy progress. The lake margin was our guide for many miles. A couple of days later we were in broken country again. There was a cluster of a few houses where we stayed for only one meal and on our refusal to stay overnight were given food to carry with us. We were moving well and morale was excellent. My leg wound had closed cleanly and I had discarded the bandage.

Three or four days after leaving the great lake we camped in a valley strewn with gaunt rocks where the thin vegetation struggled to exist. It had been raining and the ground was wet. Even with the tinder we carried it took a long time to get a fire going. In a shallow cave we settled down to eat what remained of our flat cakes of coarse-milled flour. The night breeze eddied the smoke from the fire about us and we sat close together for warmth. There was little to distinguish this night from dozens of others that now lay behind us. Certainly there was nothing to warn us that this was to be the setting for tragedy.

We slept, as always with the exception of Kolemenos, fitfully. One and another would awake mumbling from half-dreams to get up and tend the fire. Zaro it was who rose and went out as another day began palely to light the still desolation of the valley. I lay propped on one elbow as he came back.

‘There’s some mist about and it’s cold,’ he said to me. ‘Let’s get moving.’ He stepped over the others, rousing them one by one. Paluchowicz lay next to me, Marchinkovas was huddled between Smith and Kolemenos. I stood up and stretched, rubbed my stiff legs, flapped my arms about. There was a general stirring. Kolemenos pushed me with elephantine playfulness as I limbered up.

Zaro’s voice cut in on us. ‘Come on, Zacharius. Get up!’ He was bending over Marchinkovas, gently shaking his shoulder. I heard the note of panic as he shouted again, ‘Wake up, wake up!’

Zaro looked up at us, his face tight with alarm. ‘I think he’s ill. I can’t wake him.’

I dropped on my knees beside Marchinkovas. He lay in an attitude of complete relaxation, one arm thrown up above his head. I took the outstretched arm and shook it. He lay unmoving, eyes closed. I felt for the pulse, I laid my ear to his chest, lifted the eyelids. I went through all the tests again, fearful of believing their shocking message. The body was still warm.

I straightened up. I was surprised at how small and calm my voice was. ‘Marchinkovas is dead,’ I said. The statement sounded odd and flat to me, so I said it again. ‘Marchinkovas is dead.’

Somebody burst out, ‘But he can’t be. There was nothing wrong with him. I talked to him only a few hours ago. He was well. He made no complaint…’

‘He is dead,’ I said.

Mister Smith got down beside the body. He was there only a minute or two. Then he crossed the hands of Marchinkovas on his chest, stood up and said, ‘Yes, gentlemen, Slav is right.’ Paluchowicz took off his old fur cap and crossed himself.

Zacharius Marchinkovas, aged 28 or 29, who might have been a successful architect in his native Lithuania if the Russians had not come and taken him away, had given up the struggle. We were stunned, we could not understand it, we did not know how death had come to him. Perhaps he was more exhausted than we knew and his willing heart could take the strain no more. I don’t know. None of us knew. Marchinkovas the silent one with the occasional shaft of cynical wit, Marchinkovas who lived much with his own thoughts, the man with a load of bitterness whom Kristina had befriended and made to laugh — Marchinkovas had gone.

In the rocky ground we could find no place to dig a grave for him. His resting place was a deep cleft between rocks and we filled up the space above him with pebbles and small stones. Kolemenos carried out his last duty of making a small cross which he wedged into the rubble. We said our farewells, each in his own fashion. Silently, I commended his soul to God. The five of us went heavy-footed on our way. With us went Marchinkovas’s fufaika and sable waistcoat. We thought they would be useful to us.

The country changed again, challenging our spirit and endurance with the uncompromising steepness of craggy hills. We learned to use our wire loops as climbing aids on difficult patches. We tried always to find a village to spend the night under cover but all too often the end of the day overtook us in the open with no human settlement in sight.

Once from the heights we saw, many miles off, the flashing reflection of the sun from the shining roofs of a distant, high-sited city, and it pleased us to believe that at least we had seen the holy city of Lhasa. What we saw may have been one of the greater monasteries of Tibet, but the direction was right for Lhasa and the idea of having seen it after using its name like a talisman all the way from the borders of Siberia appealed to us.

Towards the end of December we came across the biggest village of our Tibetan journey, almost a small township of some forty houses arranged with an unusual regularity on each side of the road. It had, too, the unusual refinement of a larger building which in Europe would certainly have been the village hall. We were taken along to this building by a villager who was well padded and clothed against the cold and we remarked on the way on the absence of children. The reason emerged when our escort fetched out from the building a slim, lean-faced, sharp-eyed Asiatic who may have been between thirty and forty. He looked us over, bowed, smiled and went back inside. A minute later a couple of dozen children exploded out and scampered down the street, throwing us glances as they went. The place was a school and the thin man apparently their teacher.

I am sure he was not a Tibetan. Chinese? I could not be sure. Three or four Tibetan villagers stood beside us as he came out a second time and there was an exchange of conversation between them and him the gist of which was that we were foreigners who did not understand their language. That much seemed obvious. He spoke to us in a couple of languages, which may have been Tibetan and Chinese, enunciating slowly and carefully. I said a few words in Russian and Zaro spoke in German. We were getting nowhere.

We stood there awkwardly for a minute, the Tibetans looking anxiously on. The teacher spoke again, very slowly. His language this time was French. Zaro fairly threw himself into the fray. The words tumbled from his lips. The teacher smiled and put up his hand, motioning Zaro to speak more slowly. Zaro complied. They talked together with evident enjoyment. It was a talk with a wealth of gesticulation on Zaro’s side and many re-shapings and simplifications. The Tibetans were delighted with the way things were turning out and beamed on us all.

Читать дальше

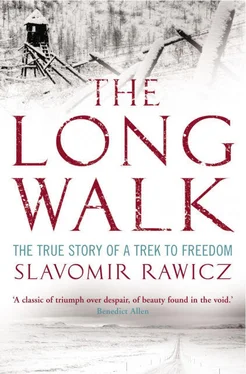

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)