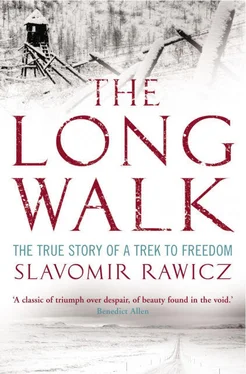

We were given more meat, more oaten cakes, more tea. Then it was time to go.

‘When you come back this way,’ said the Circassian earnestly, ‘do not forget this house. It will always be a home to you.’

The American answered, ‘Thank you. You have been very kind and generous to us.’

I said, ‘Will you please thank your wife for all she has done for us.’

He turned to me. ‘I won’t do that. She would not understand your thanks. But I will think of something to say to her that will please her.’

He spoke to her and her face broke into a great smile. She went away and returned with a wooden platter piled with flat oaten cakes, handed them to her husband and spoke to him.

‘She wants you to take them with you,’ he told us. We shared them out gratefully.

There was one other parting gift — a fine fleece from the man, handed over with the wish that it might be used to make new footwear or repair our worn moccasins. We never did use it for that purpose, but later it made us half-a-dozen pairs of excellent mittens to shield our hands from the mountain cold.

He walked with us out of the village, pointed out our way. For the only time in our travels we received specific and detailed instructions of our route.

‘Some of the tracks you will follow will not be easy to find,’ he warned. ‘Don’t look for them at your feet; look ahead into the distance — they show up quite clearly then.’

He described landmarks we were to seek. The first was to be a crown-shaped mountain about four days distant and we were to take a path which would lead us over the saddle between the two north-facing points of the ‘crown’. From the heights we were to set course for a peak shaped like a sugar-loaf, which we would find to be deceptively far away. It might take us two weeks to reach it, he thought. More than that he could not from here tell us accurately, but eventually we should reach a road leading to Lhasa which at some point forked east to the city and south-west to the villages of the Himalayan foothills.

We left him there, a little knot of children at his heels. When we turned round he made a most un-Mongolian gesture — he waved his arm to us. The last we saw of him was a figure still waving a farewell.

Marchinkovas spoke for us all when he said, ‘These people make me feel very humble. They do a lot to wipe out bitter memories of other people who have lost their respect for humanity.’

For a few days we were on the look-out for Chinese troops, but we met no one and saw no one. We disciplined ourselves not to touch our oatcakes until the third day — we had three each — and then we spread out the eating of them as an iron ration. Our track was clearly marked and the way was not too hard. There were plenty of small bushy trees something like the dwarf junipers of Siberia which burned brightly and gave out good heat. At the end of the fourth day we camped at the foot of the crown-shaped mountain and started our climb at first light the next day. The ascent was long but not difficult and the crossing occupied us two days.

It had been fully a week since our last real meal when we came across a mixed herd of sheep and goats and found the two houses of the Tibetans who owned them. The day was warm and brightly sunny after the freezing temperatures of the heights. There were scattered bushes of a species of wild rose, attracting the eye with gay blooms of yellow and red and white.

The house into which we were taken by the Tibetan herdsman was in the same style as that of the Circassian but smaller and not so well equipped. But the courtesy and the hospitality was of the same impeccable standard. The family consisted of the man and his wife in their middle thirties, a woman of about 25 who could have been the wife’s sister, and four children whose ages ranged from about 5 to 16. We were given milk to drink on arrival and later two massive meals of goatmeat. By signs we were urged to spend the night and willingly accepted the offer. The whole family turned out to bow their farewells in the morning.

After about an hour’s walking Marchinkovas stopped to examine his moccasins and found the rocky going had worn a hole through one of the soles. We all sat down with him and had a mending session. All our shoes were in a bad state. Some of the repairs involved almost complete remaking.

The explicit directions of the Circassian led us unerringly to the looming bulk of the sugar-loaf mountain and over it. The crossing would have been easier for me had not my old leg wound just above the ankle started to break open. I made a bandage by cutting a length of the rough material from the top of my sack, but the wound remained sore and painful to touch.

For a well-accoutred tourist or explorer the country would have presented a picture of inspiring grandeur, range after range thrown up in some primeval convulsion of the earth’s crust. To us it was a country besetting our escape route with obstacles. Our suffering feet were the arbiters of judgment and Tibet was cruel to them. There were nights when in the dancing lights of a blazing fire I could have slept soundly, but my feet, punished on a rocky climb, kept me awake, throbbing, aching and protesting at the burden put upon them. Pulses of pain reminded me, too, of the spite of a German grenade fragment which I had not felt at the time it thudded home.

On the other side of the sugar-loaf we found a stretch of country which presented comparatively easy travel. In the distance, throwing back the sun’s rays we saw a lake about four miles in circumference. With visions of bathing and refreshing ourselves in its inviting waters, we hastened towards it. I tore my moccasins off and dipped both feet in. The cool water stung. Zaro cupped some of it in his two hands and took it to his lips. A second later he was spluttering and spitting it back. The water was salt, more strongly impregnated with salt than the sea, stiff with the stuff. I let my feet soak but I did not attempt to drink. We moved on to look for fresh water but after a few hours my ankle became so sore that I stopped to examine it. The wound was festering and I became racked with worry that it might halt me altogether.

Before the day was out we reached a fast-flowing river, chuckling over its stony bed. Here we drank and washed ourselves. The water raised goose pimples on our skins but the sun dried us and we felt better. Paluchowicz advised me to soak and rub my hessian bandage before replacing it about my ankle. I did as he said and hoped for the best.

We had deviated a couple of miles off our course to reach this river, which flowed, as far as we could judge, directly from north to south. For several days we followed it along. It made for easier travelling along fairly flat ground and we avoided the probing cold of the higher altitudes. In the end it turned on a sharp bend to the west and we swam it so as not to be diverted off our southerly course. My ankle was less troublesome, the skin showed signs of healing and the discharge from the wound had almost stopped.

We were in great need of food again and made detours if we thought a greener valley might support flocks and people. Marchinkovas had trod on a sharp spur of rock and was limping. We knew that we had to find somewhere to eat and to rest for a day.

THE WEEKS dragged on, October made way for November, the days were cool and the nights were freezing. Over long stretches of country too barren to support even sheep and goats we sometimes went for four and five days without food. There were bleak, mist-enveloped mornings when I felt leadenly dispirited, drained of energy and reluctant to flog my weary body into movement. We all had our bad days in turn. The meals we were so generously given were massive but we lacked fresh green-stuff. The result was that we continued to be ravaged by scurvy. But we counted ourselves fortunate that no member of the party suffered a major breakdown in health and the march went on. We swam turbulent rivers when we had to. We negotiated formidable-looking peaks which turned out on closer acquaintance to offer surprisingly little difficulty; we struggled over innocent-looking hills which perversely offered precipitous resistance to our advance.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)