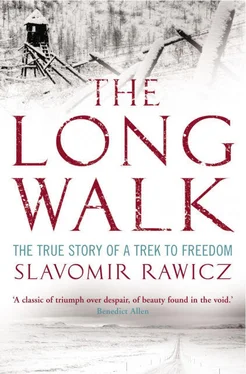

Marchinkovas one night started a discussion on the advisability of pressing on right through to the Himalayas. He thought we should consider going to Lhasa or some other city where we could live for a time and build up strength for the last stage. He was mildly supported by Paluchowicz. The rest of us were against wasting time. I was afraid such temporizing might soften the hard core of our resolution. The months had built up a compulsive migrant force in us, a rigid, driving habit of movement, and I wanted no interference with it until we had reached the final and complete safety of India.

The American put up the practical consideration that we might not find ourselves so warmly welcomed by the officialdom of a big city as we had been by the country people. There might be awkward questions, demands that we should produce papers.

Marchinkovas was not insistent on his idea. He had thrown it in to sound out opinion and was quite content with the outcome. It had not been a suggestion born of any sense of defeatism. Marchinkovas was as convinced of eventual success as the rest of us. We could not afford to think of failure.

It was about this time that we found a use for the strong wire loops we had brought with us out of the desert. We found our way blocked where the track over a hill had been broken away by a fall of rock. To get round we had to face the climber’s hazard of an overhang surmounted by a sharp spur. We made a ten-foot length of plaited thongs, tied it firmly to Kolemenos’s loop and had him from his superior height try to lasso the tip of the rock spur. It took a dozen throws before the wire settled over. Then, gradually, Kolemenos put the strain of his still considerable weight on the rope. It held firm. Zaro, as one of the lighter members, volunteered to go up first. He climbed with great care, not trusting absolutely to the rope but making use of what slight hand- and foot-holds there were. With Zaro tending the anchored end, we all made it quite easily, Kolemenos climbing last.

There was a well-spaced-out succession of unremarkable villages and hamlets, alike in their simple architecture and in the full measure of hospitality they accorded us. They presented no feature by which I can remember them individually. But there was one we found at this time that stands out sharp in the memory because of a most unlikely encounter.

The place was so small and so well tucked away, just six close-grouped houses, that we might easily have passed it by had not our route brought us just within sight of a corner of it. We were escorted in by a smiling young Tibetan who seemed to be unduly excited at the discovery that we spoke an unintelligible tongue. He led us with an unusual show of urgency to a group of men standing outside one of the houses. One of them was so much taller than the Tibetans with whom he was speaking that he immediately drew our attention. He turned with the others as we came up and we saw with surprise he was a European. Our escort performed the introductions and we saluted the villagers with bows, which were returned. The European inclined his head slightly. He scrutinized us so long that I began to feel a little uncomfortable.

This was a man of about seventy whose grey hair still retained traces of the sandy colouring of his youth. He was fully six feet tall and stooped slightly. He looked, despite his age, powerfully framed and well muscled. About him was the air of the man who has lived out of doors for many years; his strong hands and long, intelligent face were deeply tanned. His Tibetan-style clothes were topped by a thick, knee-length sheepskin surcoat, around which was a narrow black leather belt. It was difficult to see the colour of his eyes because the sun glinted off a pair of steel-rimmed spectacles, in themselves oddities in these surroundings. The Tibetans were standing round, looking expectantly from him to us and then back to him again. I thought it time someone broke the ice. I addressed him in Russian. I could almost feel the quickening interest of the local audience.

The tall man shook his head, paused and spoke — in German. Now Marchinkovas, Kolemenos and Zaro were as well versed in German as I was in Russian and delighted at the chance to exercise their skill. Paluchowicz and I knew enough to follow the conversation but I do not know whether the American could understand. I was struck by the stranger’s reserve. He spoke shortly and crisply, answering questions precisely and volunteering nothing. He told us he was a missionary, a nonconformist, who had come here with a handful of Europeans of the same persuasion. He had been travelling in China and Tibet for nearly fifty years. I think he was either German or Austrian.

For no apparent reason he switched to French. Zaro spoke the language extremely well and carried on some talk with him before they reverted to German. The Tibetans were listening in open-mouthed fascination at the flow of strange sounds. I had the strong impression that our new-found acquaintance did not like us. I think probably the cause of it was our appearance — the dirty matted hair, our torn clothes, our complete poverty. It seemed to me that in this and other villages he enjoyed a prestige as a Westerner built up and consolidated over long years. He might well have thought that the advent of six battered European tramps might weaken his reputation with the natives.

Zaro, who was doing most of the talking on our side, soon sensed that our arrival here was not entirely a pleasure to the stranger. It brought out the imp in Zaro. He answered the missionary’s questions with jaunty insouciance. He described us as ‘a group of cosmopolitan tourists’ and airily evaded an answer to the inquiry of where we had come from.

He looked frankly unbelieving when Zaro said we were travelling to Lhasa as pilgrims and in a few minutes there had developed an unmistakable atmosphere of mutual distrust. Only the Tibetans were enjoying the exchanges — and they did not understand a word.

‘You carry nothing with you. How do you live?’

Zaro replied, ‘Through the hospitality of the country. The people are very kind, as you must have discovered.’

‘But you are not able to eat every day in that manner?’

‘We take less than we need,’ said Zaro. ‘There are many days when we pull in our belts. We are used to it.’

Marchinkovas broke in to ask the missionary where he lived. The man pointed to a mule cropping grass a few yards away. ‘That is my mule. Wherever it stops, that is my home.’

Our entry into the village was about ten o’clock in the morning. The missionary sat with us while we ate — I remember particularly about this place that we were given rice and I wondered where it had been grown. He talked a little but it was a strained meal. He was puzzled by us and did not know how to tackle us. About three o’clock in the afternoon he announced that he would be moving on. We walked outside with him and he went off on a round of calls at the houses. He saddled his mule and looked round at us as he prepared to depart.

In German he said, ‘I wish you luck wherever you are going.’ We thanked him. He did not offer to shake hands. He said his farewells to the Tibetans and walked away, leading the mule.

The Tibetan who had made himself our host watched him go and then made signs to us, drawing himself up, thumping his thrust-out chest and flexing his muscles. He was trying to tell us, I think, that the parting guest was, or had been, a man of great physical prowess. I felt a spasm of regret that the meeting could not have been more friendly. With the barriers down between us, he could have told us so much we wanted to know.

The inevitable bunch of sharp-eyed, inquisitive children surrounded us as we made to follow our host back to the little house. One little fellow of about eight plucked at Zaro’s trousers. Zaro made monkey faces at him. The children, about a dozen of them, crowded laughing about him. Zaro did some more clowning and the children loved it.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)