MELANIE McGRATH

The Long Exile

A True Story of Deception and Survival in the Canadian Arctic

‘An Eskimo lives with menace, it is always ahead of him, over the next white ridge.’

ROBERT FLAHERTY

Preface

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Epilogue

Selected Bibliography

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

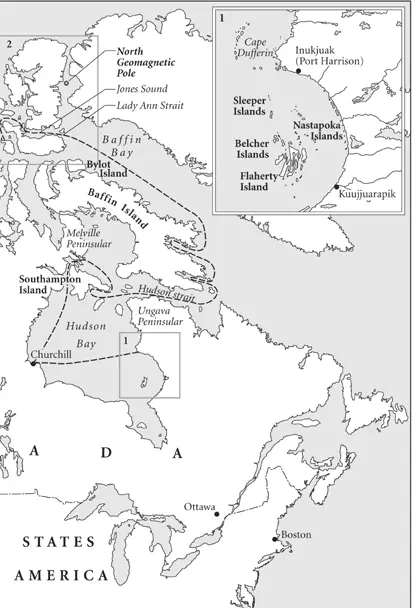

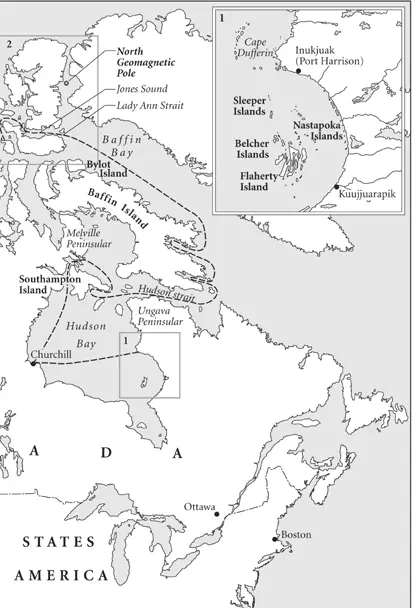

There have been many books written about the Arctic, mostly tales of explorers and derring-do. This book isn't one of those. It is rather the story of a movie and the legacy left behind by its maker. The film is Nanook of the North , which has been described by filmmakers as diverse as Orson Welles and John Huston as one of the greatest pictures ever made. Its Irish-American director, Robert Flaherty, arrived in the small settlement of Inukjuak on the east coast of the Hudson Bay in 1920 to make it. He filmed it in a year, but was haunted by it for the rest of his life. The movie's success helped colour the western view of Inuit life in the Arctic for generations. It does so today. Flaherty never returned to the Arctic, but he left a son there, who grew up Inuit. More than thirty years later, a group of Inuit men and women were removed from Inukjuak by the Canadian government and taken hundreds of miles north to the uninhabited High Arctic. Among them was Robert Flaherty's son. This book is as much about Josephie Flaherty and his family as it is about his father's movie.

It is often said that the Inuit have dozens of words for snow. While this is true it doesn't tell the whole story. The Inuit do have many words to describe snow, but they also differentiate between various kinds of snow those of us who don't live in the Arctic would see as being essentially the same. It's not so much that the Inuit have dozens of words for snow, as that, in the Inuit world, there are dozens of different kinds of snow.

There are also emotional differences in the way Westerners and Inuit view the world. Until very recently, emotions like envy or sexual possessiveness were so perilous to the equilibrium of the Inuit – living as they did in family groups, often separated from each other by thousands of square miles of ice and tundra – that they were vigorously discouraged. There was a time when expressing rage, lust or ambition was considered so threatening to the group's survival that persistent offenders were ostracised from the community and sent to their deaths on the tundra; some persistent offenders were even killed outright, often by their own families. For thousands of years, these threatening emotional traits were suppressed to such a degree that they were rarely felt among the majority. Other, more helpful traits crept in to take their place: modesty, patience, acceptance of group decisions and a sense of being not just bound to the group, but being an integral part of it, a vital organ in the family body. These are more common and more valued character traits among Inuit even today than they are among people living in large cities in the West.

Although it regularly occurs, we are not necessarily aware of a similar process of emotional editing taking place in our own lives. It's not hard to recall feelings those of us living urban lives have allowed to wither: a wonder and respect for nature, a feeling of being at one with the land, an inexorable identification with home and family, a sense of belonging. We may regret the passing of these feelings; indeed, if our appetites for nostalgia are anything to go by, we certainly do, but few of us would want to go back and live as our great-great grandfathers and grandmothers lived; nor must we in order to feel respect, even awe, for what our ancestors endured and the kind of people they were.

It is easy to feel disconnected from human beings to whom we are neither related by blood nor fate and with whom we share few cultural connections; people whose range of emotional expression and personalities may feel very different from our own or from anyone we know.

And so, when you read this story, bear this in mind; however many kinds of snow there are and however many words for them, they all, in the end, melt down to water.

In the early autumn of 1920, Maggie Nujarluktuk became a woman with another name. It happened something like this. Maggie was sitting on a pile of caribou skins. She had a borrowed baby in her amiut , the fur hood of her parka. A man was filming the scene. His name was Robert Flaherty. Maggie was about to pull the baby out of the amiut and set him to play beside a group of puppies as Flaherty had instructed, when looking up from his camera, he said, ‘Smile’, grinning to show Maggie what he was getting at and told her, through an interpreter, that he had decided to change her name. She laughed a little, perhaps conscious of his eyes, blue as icebergs, then lifted the baby into her arms, placed him beside her and pulled the puppies closer to keep him warm.

‘Well, now, Maggie,’ Robert said. He winked at her, wound the camera and lingered on her face. She watched his breath pluming in the chill Arctic air.

‘How's about Nyla?’ He allowed the name to roll around his mouth. ‘Yes, from now on you are Nyla.’

If Maggie minded this, she didn't say. She already knew she has no choice in the matter anyway.

Maggie Nujarluktuk was very young back then (how young she didn't know exactly), and very lovely, with a broad, heart-shaped face, unblemished by sunburn or frostbite or by the whiskery tattoos still common among Ungava Inuit women. Her thick hair lay in lush coils around her shoulders and her skin and eyes were as yet unclouded by years of lamp smoke or by endless sewing in poor light. Her lips were bowed, plump but fragile-seeming, and it was impossible to tell whether her smile was an invitation or a warning. Beneath the lips lay even teeth that were white and strong, not yet worn to brown stumps from chewing boots to make them soft. And Robert Flaherty had just renamed her Nyla, which means the Smiling One.

Robert Flaherty's movie had begun in something of a rush. Only three weeks earlier, on 15 August, the schooner, Annie , had dropped anchor at the remote Arctic fur post of Inukjuak, on the Ungava Peninsula on the east coast of Hudson Bay, and a tall, white man with a thin nose and craggy features had come ashore with his half-breed interpreter, introduced himself to the local Inuit as Robert Flaherty, and announced his intention to stay in the area long enough to make a motion picture there. The film, he said, was to be about daily life in the Barrenlands.

The stranger moved into the fur post manager's old cabin, a peeling white clapboard building on the south bank of the Innuksuak River and hired a few hands to help him shift his things from the shoreline where the Annie 's crew had left them. Among the expected baggage of coal-oil lamps, tents and skins were the unfamiliar accoutrements of film-making, lights, tripods, cameras and film cans, plus a few personal belongings: a violin and a wind-up gramophone with a set of wax discs and three framed pictures, one a photograph of Arnold Bennett, another of Flaherty's wife, Frances, the third a little reproduction of Frans Hals' Young Man with a Mandolin . The number of possessions suggested that Robert Flaherty was settling down for a long stay. Within a day or two of his arrival, he had hung his pictures above the desk in his cabin, lined up his books along a home-made shelf, rigged up a darkroom, setting several old coal-oil barrels outside the door to serve as water tanks for washing film, and found three young men he could pay to haul his water and supply him with fresh meat and fish. By the time a week was up, the cabin looked as though it had always been his home and Flaherty was busy assembling his lights and cameras and running tests. In the evenings, he could be heard humming along with his gramophone (he was particularly fond of Harry Lauder singing ‘Stop Your Ticklin' Jock’) or playing Irish jigs on his fiddle.

Читать дальше