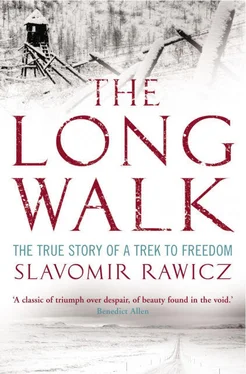

We picked out the best of the huts and decided to sleep there the night. On the earthen floor was a blackened, hard-baked circle with a few charred pieces of wood, and overhead there was a small hole in the roof. Here we built our fire, splitting up some bamboo for fuel and banking it up for the night with animal dung which Zaro carried with him.

In February we encountered our last village, just eight or nine houses snuggled in a hollow a couple of hundred feet above a narrow valley. Behind the village reared the forbidding rampart of tall hills over which we had struggled for two days. Across the valley, hazy in the light of a wintry afternoon sun, another range heaved itself up towards the clouds. The houses had, for Tibet, a rare distinction. They were the only two-storey buildings we saw in the whole country, or, indeed, since we had left Siberia. We had descended to a point west of and below the little settlement and had to climb up to it along a rough track. We were profoundly tired, miserable and hungry. Paluchowicz was limping on his right foot, the arch of which had been bruised when he trod on a sharp stone.

The Tibetans, when they understood by signs whence we had come and where we intended to go, showed amazement at our hardihood, or foolhardiness. We were gently ushered into one of the houses, made to sit down on low benches polished with years of use, fussed over, given steaming hot tea and fed with mutton and the usual filling oaten cakes. Paluchowicz was given some grease, possibly sheep fat, to rub into his sore foot. From all the houses men and children came to look at us. There was much smiling and bowing and slow nodding of heads. Undoubtedly our arrival was an extraordinary event and would long be a topic for wondering talk.

In this house was an excellent example of a building custom we had noted throughout Tibet — a flat-faced stone on which three or four lines of an inscription had been cut. This one had been built in near the door and about two feet above floor level. The Circassian had told us that these tablets could only be made by certain lamas and that the Tibetans set great store by them, for the words upon them were a holy injunction to the spirits of evil and misfortune to keep their distance. Our host, rather taller than the average Tibetan and aged, I guessed, about thirty, seemed pleased at my interest in his lucky stone. He came over, pointed to it and then to his left wrist, on which I saw a broad brass bracelet to which was attached a small metal box. This was, to me, a new variation of the prayer-wheel, and I think it is obvious the man was trying to show a religious connection between it and the inscription on the stone.

These people were skilled weavers. In the main downstairs room was a spinning wheel and a small loom, and the woollen material they produced was thick, warm and of good quality. The best examples of their work I saw were in blankets and bed coverings in gay and bold colours of red and yellow. The sheep which provided the wool were at this time in their winter quarters, a big dry-stone pound along one side of which were long, low stone sheds to protect them from the worst of the weather.

The link between upper and lower floors was a short, steep flight of rough-shaped stone steps leading out of a corner of the big lower room. There was no handrail and one entered the room above through a square aperture as though emerging from a hatch in a ship. Upstairs were the family sleeping quarters and a store for tightly-packed bales of wool. Here, in the warm, stuffy smell of sheep, we slept the night in cosy comfort while the wind moaned and whined around the thick walls outside. Daylight woke us gradually as it struggled through the tiny single window of thick mica stuff.

While we ate a substantial morning meal we were amused to watch the Tibetan householder going around our worn old sacks lifting them and feeling at the contents.

Said Zaro, ‘Perhaps he’s making sure we haven’t packed up the family silver.’

The Tibetan could not have known what was said, but he was pleased to see us laughing and joined in, completing his round of our belongings as he did so, finding out in the process that all we were carrying was an assortment of pieces of fur and fleece, and sticks and animal stuff for fire-making. When the investigation was over, he looked at us with some concern, pointed to the sacks and indicated the food we were stuffing into ourselves.

The American said, ‘He is worried because we are travelling without a supply of food.’

He went off into the little back room and we heard him talking to the womenfolk. Then he passed through and out of the front door, followed by a youth of fifteen or sixteen. They were absent about half-an-hour and when they returned they carried a young sheep freshly killed and skinned. The carcase was split down the back and for some hours the two women of the house busied themselves with the task of roasting the meat on spits over the open fire.

Meanwhile the man walked round us all and examined our cut and bruised feet. He took himself off up the stone stairs and brought down a bundle of raw wool. Demonstrating with one of Paluchowicz’s moccasins, he showed how the stuff could be used to insulate the feet against cold. He pulled out fistfuls of the wool and handed them round. The idea was excellent and I think we managed to convey our thanks to him.

When we left the little mountain hamlet we were loaded down with food, which included a complete side of the roasted sheep. Up to now we had kept whatever eatables we had been given in one sack, which was carried in turns. We decided at this stage to share the meat and flat cakes equally between us because of the danger of losing the lot if the precious single sack disappeared with its owner on one of the increasingly difficult climbs we were now encountering.

The Tibetan escorted us about half-a-mile on our way along a narrow track above the valley. Left to ourselves we should have dropped down to the lowest point and started on the stiff ascent on the other side in order to maintain our direction due south. He, however, gestured insistently southwest along the track and to each of us in turn indicated in the far distance the landmark of twin peaks which we understood we were to cross. He bowed us off on our journey, then turned and went back the way he had come.

‘God be with you,’ said Paluchowicz fervently, in Polish.

It was early afternoon and with what remained of the day we covered possibly ten miles of fairly easy terrain. That night, around a small fire, we sat talking for hours trying to assess our position and how much farther we had to go. When the conversation flagged, the extraordinary stillness and silence of the brooding mountains engulfed us. I had a feeling of great pity for myself and for us all. I wrestled with a desperate fear that now, with thousands of heart-breaking miles behind us, the odds might be too much for us. Often at night I had these bouts of despair and doubt. The others, too, I am sure, fought the same battles, but we never voiced our waverings. With the coming of morning the outlook was always more hopeful. Fear remained, a lurking thing, but movement and action and the exercise of the mind on the daily problems of existence pushed it into the background. We were now, more strongly than ever, in the grip of the compulsive urge to keep moving. It had become an obsession, a form of mania. Like automatons we set out each morning, triggered off by a quiet ‘Let’s go’ from one or another of us. No one ever pleaded for half-an-hour’s respite. We just went, walking the stiffness out of our joints and the chill of the dark hours from our bodies.

We rationed the food out thinly and it lasted, one meal a day, for over a fortnight. It was insufficient for the heavy climbing and the perilous descents in which we were now involved but at least we had the comfort of knowing we could not starve while it lasted. Several times we were caught out on the heights and had to resort to the lessons of our Siberian experience in making a snow dugout and holing up sleepless until the dawn of another day.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)