And so, throughout the year when I wrote that book, I felt as if my clothes and then my skin were gradually peeled away. And in the end I found myself running around naked in the small, empty flat I was working in, looking for clothes to cover myself. This process extracted from me things that people don’t talk about, even things I never knew I ever knew. There were days when I fled my writing desk and ran into the street, being driven half crazy by the devil pushing my pencil across the page.

Time and again I decided to retake control of my book and to return it to the path I had chosen for it—just a simple war story—but Toledano wouldn’t submit. He was there, he had a forceful personality, and he wanted to speak. So whenever I returned to that small flat and the piles of scribbled pages, I found that my control of the situation was at best partial, and I couldn’t do with my hero what I initially planned. There came a moment when I considered killing him off, but I failed. It was Toledano’s fault that the entire book charged off in another direction, and other characters began their own revolution, and also tried to rewrite their stories through me.

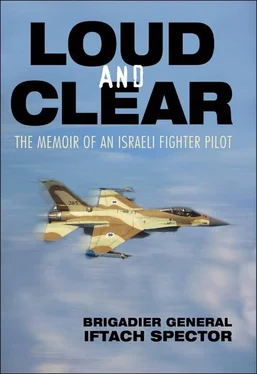

And I cannot blame anybody, because A Dream in Black and Azure came out okay in the end. At least that’s what people told me, and to this day occasionally people grab me on the street, call me up, or send letters telling me things about it and about themselves from its pages. That book even won me a literary prize. I was invited to share the stage where none other than the prime minister, Mr. Yitzhak Rabin, was waiting for me. So Yitzhak shook my hand again and again, and then he turned from me to the microphone and said in his deep bass voice, “Iftach Spector surprises us again.”

And, all in all, it was really nice, although I couldn’t remember any previous surprises I had given Mr. Rabin. And in truth, it should have been Toledano standing there on the podium before that big audience and getting an award, not me. Because it was Toledano who had surprised the prime minister no less than he surprised me.

Days and years later, I have decided that there is still something special in the first person: it is mandatory. And over it, together with it, comes the special flavor of authenticity. Now I realize that it was with good reason that for the hardest of Odysseus’s tribulations, Homer gave him the mike, telling him to speak for himself. The dilemma is clear: How does the poet get inside the head of the man who tied himself to the mast and listened to the singing of the Sirens until he went mad? And who, except the one who dared to descend to the underworld, could imagine the emotions and the thoughts that flooded him when he met his dead mother there?

SO NOW, HAVING STARTED another session with blank pages, I recall Toledano and think that though the word “me” irritates, it still has one exclusive quality: this word is at least clear and binding. Surely it’s much easier to blur things; obscurity would have made the telling much easier on me, but I fear that compromises may damage the final product. Take A Dream in Black and Azure . With all the praise and the award, who remembers it now?

Well, for sure, one man—a high-ranking officer in the IDF does. He swore, after I declared I would refuse to take part in war crimes, that he was going to destroy and annihilate my book. Erase it from under the sun.

When I heard about him and his threat, I was astounded. Initially I thought there might have been some mistake in the last edition that somehow insulted him personally. So I checked in my copy, and the text was okay. On reflection, I decided that the book had nothing to do with him, and the important thing to this person was just the proclamation of its annihilation. I thought that probably his reward would be an invitation by his superiors for a macho pissing with the wind, a hell of a promotion. If this was really the case, I salute him. This officer must be practical, a man of action, and surely he has the “right stuff,” a man with a great future. I am glad my book helped him to get there.

SO THIS IS MY CONCLUSION after all these deliberations: I have decided that my small odyssey will be told by myself, under my own name. I shall not compromise anything intentionally.

NOW HERE WE ARE BACK IN THE EARLY 1960s, at the Scorpions.

Two months have passed since our arrival; I haven’t yet passed my flight test. Yak himself was invited from headquarters and came down to the Scorpions to check out the trainees on the Super Mystere in aerial combat, one on one, against him.

Now it was my turn.

“Turn out,” he ordered. We separated, turning away and preparing for battle. Then he reversed direction and turned back toward me. He came nearer and nearer, the master battle tactician, and—wham!

We passed each other head on, at supersonic speed.

I ignored his wake turbulence rocking my ship and pulled up hard on the stick. My aircraft climbed vertically to altitude. He climbed, too, and we met again, this time at low speed, joining aggressively.

My Super Mystere shook under me, exactly like the Harvard a year ago, but this time I was not a kid anymore and knew what to do. Yozef Salant had already prepared me for this test.

“Don’t give him an inch. Yak wants to see that you know how to be aggressive.” And he continued his lesson, “Be careful of Yak. He is cunning as a Greek. He’ll offer you his tail like a whore, but if you take it, he’ll throw you forward all the way to Baghdad.”

And so I almost smiled when Yak waggled his tail at me, and instead of jumping on it, I pulled up over his aircraft and caught “a good seat on the veranda” over his head. Yak changed tactics, climbed toward me, and we circled again like two mad dogs till the red fuel lamp came on with a beep. I sighed with relief; it was over, and I hadn’t lost.

Yak led me back to land. When we were back on the ground, my feet hovered an inch above the tarmac.

In the squadron briefing room, after a glass of cold water, Yak uttered only five words that I shall never forget: “You impressed me some today.” I blushed, and looked around to see if anybody else had heard it. Hell, where was Zorik? Why, on this day of all days, was he not here, eavesdropping, as usual?

ON FRIDAY NIGHT, WHEN ALL the kibbutz youth were singing and dancing in the main dining room, I gave Ali the eye to meet me in the corner. Would she come? She was not mine yet.

She came, curious. I told her I had had a dogfight with Yak.

“So?” She didn’t get it.

“Yak,” I told her excitedly, “the man who broke all the rules, who opened new vistas in aerial combat. It was Yak who taught the IAF how to split and fight independently, in a coordinated way, rather than in tight pairs, like that.”

I demonstrated the meaning of coordination with my hands, and knocked over a stack of china cups. And as we crawled together on the floor collecting the broken china I whispered, unable to hide a quiver of pride from my voice, “I was his equal today. We came out even.”

In the shade, below the table, I stole a fast sniff of her neck.

For long time after this special flight, I believed I knew the secret of how to win in aerial combat. The lesson I learned from that flight was that it was all about aggressive handling of the aircraft. Just fly it to the limit.

Big mistake. Yak had been testing me that first semester, and I thought it was the whole story.

BUT NOT ALL IS FLYING, and not just Super Mysteres, either. The time was young and rough, and wherever there are men there are women, too. And where there are men and women, things that are better kept secret happen. Even I was finally roused from my long sleep by a woman. When this was over, the shy courting of my delicate flower changed gear. The time was ripe for decisions. It all happened one afternoon on a summery Friday.

Читать дальше