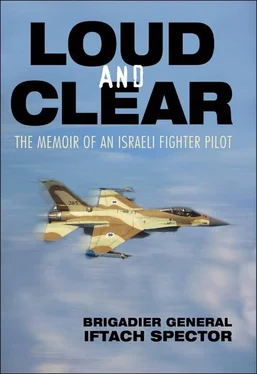

Brigadier General

Iftach Spector

LOUD AND CLEAR

The Memoir of an Israeli Fighter Pilot

We, veteran and active-duty pilots alike, who served and still serve Israel every day, are opposed to carrying out attack orders that are illegal and immoral of the type the State of Israel has been conducting in the Occupied Territories…

We, for whom the IDF and the Air Force are an inalienable part of ourselves, refuse to continue to harm innocent civilians…

These actions are illegal and immoral, and are a direct result of the ongoing occupation which is corrupting all of Israeli society…

We hereby declare that we shall continue to serve in the IDF and the Air Force on every mission, for the defense of Israel.

—The Pilots’ Letter to the Israeli Air Force, December 24, 2003

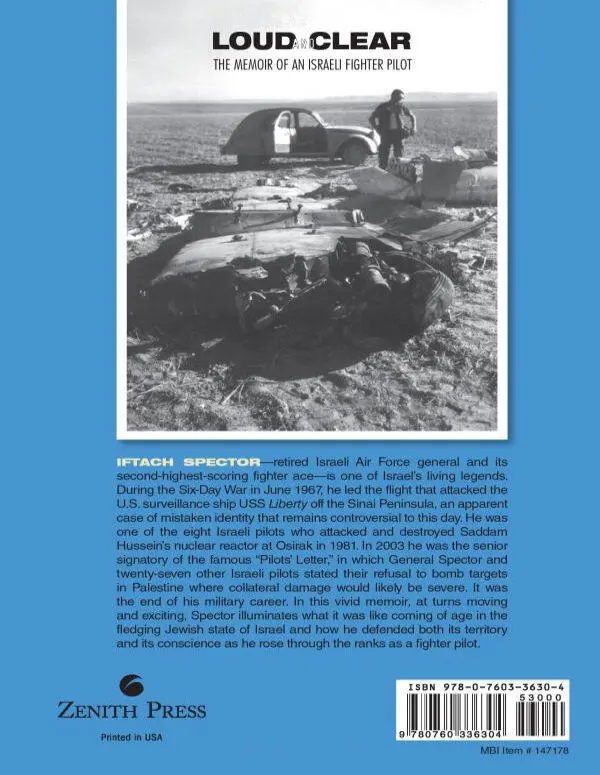

THE FIRST ISRAELI FIGHTER PILOT I ever met was Ladya. He peered at me through the grass and looked a little like cat food, reddish and granular. I collected him carefully in a cardboard box. Around us were low barbed-wire fences, and above stretched the open blue sky from which he had descended a few minutes before—passing over us with a roar, his jet rolling like a big black cross and at last slamming into the ground. Now, all around the ground was sticky and the air was saturated with the sweet smell of jet fuel.

One of my friends raised his head above the weeds and I saw his pale stare. Then I saw his back bend and heard gagging sounds. When I crawled toward him, my hand sank into a small, steaming pile. I looked at my palm—the dripping porridge of tomato pieces and white slime was not much different from the fiber and broken bone scattered around.

I vomited.

My gorge rose again forty-four years later, when the journalist in front of me combed his hair, checked his makeup in the monitor screen of the TV camera, and turned to interview me for this evening’s sound bite for Channel One. A pimple on his cheek drew my attention. Then I saw his expectant look.

“Sorry, what did you ask?”

“Brigadier General Iftach Spector, one of Israel’s greatest fighter pilots—are you a refusenik?”

“What?”

WHAT IS GOING ON HERE? My country is under attack. Terrorists with knives attack our citizens on the streets. At night, cars are hosed down with automatic weapons fire. Suicide bombers enter hotels, restaurants, and buses to subject women, children, old people, and babies to fire, shock, and a hail of shrapnel nails. Hundreds are killed, thousands injured. The country is covered with a grid of fences around public buildings, schools, and kindergartens. Armed security stands in the entrance of every mall, cinema, restaurant, and bus station. Security people and soldiers carrying weapons patrol everywhere, stand in doors and road crossings, checking hand luggage. But in spite of all this, the terror continues. And, of course, passive defense is not enough. The enemy must be attacked in his base, and so the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) and the security services are activated.

The IDF moves its center of gravity to the occupied territories. Our soldiers focus on “dealing with the civilian population,” breaking into houses, making arrests. Our soldiers smash walls and tear up floors, searching for weapons. Sometimes they catch terrorists and their handlers. When a home has been used in this manner, the family is evacuated and the house demolished. The IDF surprises the enemy time and again in the cities and in the villages, day and night. Sometime the operation ends quietly, and sometimes clashes occur in streets and on rooftops, with dead and wounded on both sides. Many terrorists and suspects are caught. The prisons are packed with thousands of Palestinians, and new prisons are being opened.

The Palestinians react with escalating savagery. Terrorists are caught—but new ones are born all the time, some of them mere children. The mullahs seduce them, promising heavenly virgins, and terrorists continue coming like zombies with their bomb belts. They launch homemade rockets that they manufacture in secret factories at night. In the mosques, on Fridays, they get their religion with an anti-Semitic flavor, justifying their abominable terror as “holy war.” It develops into a zero-sum game—either us or them.

I AM OVER SIXTY and am not an active participant in this war. For the past fifteen years I have done my reserve duty as a volunteer, teaching pilots. From the sidelines, I watched my country forced to defend itself against terror.

This is not a simple battle; the terrorists who face us wear civilian clothes. They emerge, strike, and go to ground among the civilian population. Our forces must hit the terrorists without harming the innocent population in which they immerse themselves, and this is a very complicated surgical mission. Still, it is clear that this distinction is very important—indiscriminate attacks on populations, besides being immoral, are forbidden by Israeli law, and turn the whole world against us. Attacks that cause collateral damage endanger our chances to resolve the conflict we are engaged in, and they tarnish our self-image and our way of life.

It is a tough war. I cross my fingers for the IDF every day.

THE AIR FORCE IS THE MAIN TOOL to do that important “surgery,” and for good reason. An airplane, soaring high over the conquered areas, sees without being seen. From on high it detects figures who can be identified as “bad guys” by somebody else, locks onto them, and fires on or bombs buildings reported by somebody as containing enemies.

And terrorists do get taken out, but the process is not perfect. Many noncombatants are hit as well. The ratio of combatants to noncombatants is 1:1—meaning for every terrorist we kill an innocent, and other noncombatants are wounded. This ratio is very bad. The terrorists are the ones who profit from the collateral damage. They, who target our children intentionally—exploit our misses to win the hearts and minds of the Palestinian population and world support. Sometimes, after a botched operation like this, it seems that the loss from the operation is greater than the gain. But this is the nature of war. And throughout this book you will hear about war.

ON THE NIGHT OF JULY 22, 2002, the “surgeon’s scalpel,” while excising a cancerous tumor, slipped deep into living flesh. A fighter jet was sent at midnight to take out a notorious terrorist named Salekh Shkhade. The fighter dropped a one-ton bomb on a house in a heavily populated suburb of Gaza. The bomb hit, and the house collapsed on all its inhabitants. When the dust cleared, it was found that fifteen women and children were blown to pieces together with the terrorist.

When that outcome was known, the world cried out. In Israel hard questions began to be asked. People wondered whether this was intentional, and began inquiring about the limits set upon the military. Officials began making excuses, explaining that they hadn’t imagined that so many people were living in that house. Knowing Gaza better than that, journalists dismissed this explanation. On the other side, the shrill voices of self-proclaimed patriots thundered in the streets and markets, “What the hell is all the soul-searching for? Woe to the villain and woe to his neighbor!” And if one listened hard, one could hear the thrill of satisfaction and the joy of revenge.

This bombing woke me from my long lethargy.

I have to confess that in the beginning it was not the moral question that troubled me. I saw in all this something different: What was happening to the operational standards of the IDF? “A terrorist was eliminated—great,” I thought and cheered, “Hooray for the Israeli Air Force. But why did you have to get such results in such a miserable way?”

Читать дальше