The war ended, and we returned to Hulatta. The lower camp was deserted. The kibbutz began resettling in a new place in the fields, a little farther away from the lake. The Arab village, Tleil, didn’t exist anymore, and the mud building blocks from its houses were taken for secondary use or were left to melt in the winter rain, returning bit by bit to dust and ashes.

It turned out that Aronchik didn’t die. I was taken to visit him. He was in a hospital in Haifa, on the slope of Mount Carmel. He sat on his bed with his leg in traction, and smiled at me with an obvious effort. Dvorah was also there, taking care of him. We returned to Hulatta, and another couple adopted me temporarily. After some months Aronchik arrived, limping badly.

SCHOOL STUDIES RESUMED. Somebody said that Shosh was the highest-ranking woman in the army and that David Ben-Gurion proposed that she become the staff officer for women in the newly established Israeli Defense Force. I know why she refused. She told me more than once that she opposed different military organizations for men and women. I was very proud of her.

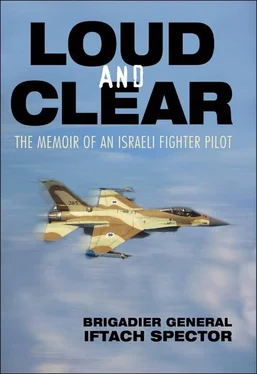

In the final photo of the Palmach, a moment before its dissolution, the staff officers stand in a half circle. Major General Yigal Alon is in the middle, and around him the men I admired: Uri Brenner, Nahum Sarig, Mulla Cohen, young Yitzhak Rabin, and others. Among them all, shorter than the men but an equal among them, stands Shoshana Spector, in a midcalf skirt with a duty belt around her waist. All the men look like serious sourpusses, but she has a wide smile, clearly refusing to give in to the general sad mood.

IN 1951 MY MOTHER RETURNED from America and took me with her to another kibbutz, Givat-Brenner, in the South. There, there was neither lake nor mountains, just orchards and burning sandy trails between acacia fences, and the kibbutz was a huge community, noisy and full of people.

My mother was a special person, very capable and with lots of personality. When she arrived at the kibbutz she was a woman in full bloom, about thirty-five years of age, extremely smart and good-looking. But she didn’t know how to compromise and never deferred to men. Once she told me that after she finished school in Ben Shemen she found work in the offices of the Jewish Agency, an organization that advised the British on issues involving the Jewish homeland, and actually functioned as a government of sorts. She was then a nineteen-year-old girl, and was sent with some documents to one of the bosses. When she entered his room her hands trembled and the papers slipped to the floor. The great man watched her, smiling, and said, “My girl, calm down. Perhaps you think I am a big shot, but when I go to the restroom my shit is as brown as anybody else’s.” She remembered this lesson and took pains to remind me of it every now and then.

A strong, single woman, she was an odd duck at Givat-Brenner. Men saw her as one kind of threat and women saw her as another kind. Like other war widows I knew later in my life, she radiated threat. Life in the kibbutz did not suit her. Indeed, though the kibbutz was a society of high ideals, in fact it was just a suburb full of petty, personal quarrels. Large clans controlled the social life at Givat-Brenner: The warm, vulgar Polish were different from the crafty Litvaks from Lithuania, and the Yekes—immigrants from Germany—were something else again. Shosh Spector, and accordingly I, didn’t belong to any of these cultures. We were outsiders—different.

In Givat-Brenner my own situation was rather better than hers. I was thrown into the seven-hundred-strong children’s society, to sink or swim among them. But I was young and still flexible. Actually, what happened to me at Kibbutz Givat-Brenner was similar to what happened to Shosh herself twenty years earlier. When she was fourteen, her father—who couldn’t support his family—sent her to a youth institution. There, in the children’s village of Ben Shemen, she found her way and her friends for life.

This is exactly what happened to me at Givat-Brenner. The beginning was tough, but eventually I made friends. The youth society I became a part of—the “brigade,” in the semi-military jargon of the kibbutz—was stormy, zealously Zionist, and naively socialist. So, like all the kids, I vowed to defend Israel, save the Jewish people, and fight for social equality and for peace and fraternity among nations. Like all of us, I was unaware of the contradictions among those conflicting goals. To find favor in the eyes of the girls, and perhaps to compensate for my incompetence on the basketball court, I became a “cultural promoter.” I became the editor, publisher, and sometimes the art director of our weekly magazine, which was displayed on walls. This was a wonderful periodical with stories and poems of local talents, such as “Captain John Marley Flies to the Moon” by Daniel Vardon, or political commentaries discussing the problem of who was going to inherit Comrade Stalin’s job when the black day would arrive. The editors bet on Georgi Malenkov, since he had no mustache. We were wrong. Khrushchev was clean- shaven, too.

On summer vacations I took every course I could get into: a month of premilitary scouting in which we traveled by foot some six hundred kilometers; a course in building model airplanes; a gliding course, and the next year piloting light aircraft. I led hikes with heavy backpacks to the three craters (unique geologic formations in the Negev Desert), and hitchhiked to Eilat on the Red Sea. Soon I was selected as a scoutmaster, and invested my evenings and weekends in my young pupils, teaching them to tie knots and make fires in the rain.

‡

SHOSH YEARNED TO LOVE ME, but the situation had become impossible for us. My mother’s social problem, and the fact that she was a stranger in this big kibbutz, threatened my standing in the children’s society. Sometimes she tried to make me her confidant and poured her toils and troubles on my head. She described her encounters with people (she was a great mimic), but this put me in an awkward situation: I had to choose whether to be on her side, or on the side of my friends. These people were their parents and elder brothers and sisters. So I listened, dissociating myself, and saw how hurt she was, but I couldn’t really sympathize enough. Soon I stopped listening to her stories and sealed myself off from her. I rolled up like a hedgehog toward my mother.

The hurt feelings between us became stronger. I began hiding to avoid being seen with her. Instead of going to her room after school, as was normal kibbutz custom, I went out to the fields or to the vacant sports arena, where I worked long hours on the horizontal bar and the parallel rings. I became the kibbutz shepherd. I took the animals out to pasture. Once in the fields, I spent many hours alone composing endless poems while my four hundred sheep ran wild and raided people’s gardens. Sometimes I woke up to the cries of furious farmers whose crops had been destroyed, and sometimes I got hit. I walked the fields and prayed for somebody to come and take me away from this place back to my real home, to Hulatta.

IN 1953, WHEN I WAS THIRTEEN, I ran away from Givat-Brenner and my mother. Before the running experiment, a dream was visiting me in the nights: I lay on a vast plain all striped in gray lines. Beyond it, heavy black lumps towered, their heads vanishing up. When I woke up I didn’t know whether this was my bed with the mattress and the lumps of blankets, or that I was on the coast of a huge marsh, and the lumps were the black mountains over it. Anyway, I felt I was home.

I decided, and at supper I filled my pockets with bread. At ten o’clock in the evening, while the kibbutz slept, I slipped out of bed and sneaked in the shadows to the entrance of the kibbutz. The road that led down to the highway to Rehovot was dark. I ran through the orchards crazily, dying of fear. I hoped to hitchhike north on the highway, to Dvorah and Aronchik and my sweet Ronnie in Hulatta.

Читать дальше