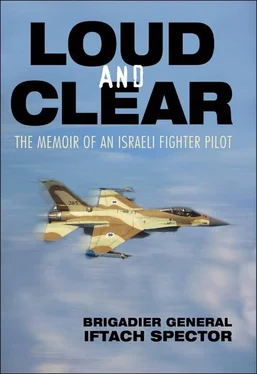

All pilots know the blackout phenomenon, when the g-load of turning acceleration forces the body’s blood down to the legs, leaving the head with diminished blood pressure. The first thing that happens is that vision becomes blurred, then totally lost, and the pilot becomes temporarily blind. Sometimes it can result in fainting. This is a similar phenomenon to what we experience when we get up too quickly after a long period of lying in bed. We sometimes black out. Recovering takes time—long seconds. Blacking out in flight can be real trouble. Fainting can be fatal.

“So when my vision came back,” I told them, “I found myself diving in a wholly different direction and not at the reactor’s yard. The reactor itself was way outside my line of approach, and I couldn’t get my bombsight on it. I thought about circling back and making a second pass, but I couldn’t forget we had orders. Ivry had absolutely forbidden us—the trailing section—to make a second approach. ‘One pass and out of there’ had been his order. Ivry hadn’t wanted a lone aircraft straggling ten or twenty kilometers behind the main force, getting everyone into trouble.”

Ivry nodded sternly.

“And I understood that. And also I wasn’t a wild kid anymore. I was a high-ranking officer and was supposed to set an example. There was no way out. I saw my target was out of reach, so I dropped my bombs on what I could in that Tammuz yard.”

I heard Nahumi gasp, and then he said, “Iftach, you have no idea the weight you took off my heart right now.”

All those years, as I hid my secret, Lieutenant Colonel Nahumi had been hiding his own secret. Nahumi, the commander of the second F-16 squadron, had led the second section of the attackers. I was his wingman. It came out now that he had blamed himself for my miss—he thought that the way he pulled up had interfered with my approach, and this was why I had missed the reactor. I hadn’t told the truth, and for twenty long years he kept his guilt inside.

Zeevik Raz said, “I’ll never forget Iftach’s face after we landed. I thought, Why is he so sad? The mission is done, and we are all back safely. What is that?”

And truly, I was very sad. And since then, whenever asked about this mission, I would answer, “Let me tell you about some other good misses. I have quite a few.” But in my heart I knew that missing the target was not my problem. The real stone that lay on my heart was not the missing, but the silence.

“I WAS SO HUMILIATED and ashamed,” I told them. “How could I miss such a big target, as big as Madison Square Garden? And so important?” For some inner reason the fact that my body had failed me was the worst part. I was a forty-one-year-old male. A psychologist might make a big deal about what had bothered me so much, but I just couldn’t share the fact that my body had betrayed me with anybody else.

“I buried this story, and you, my friends, are the first to hear it.”

Looking at Ali, who sat at the back of the room, I concluded my confession. “To this day, I hadn’t even told Ali, the same way I just kept her in the dark about the whole Baghdad mission. She never knew before the flight that we were going on that flight and that I was going there, too.” I looked at her. She looked up and sent me a quiet smile.

A GOOD WORD CAME FROM Duby. He, who had fought with me in the Yom Kippur War, on whom I inflicted many punishments when he was a young, wiseass pilot, was sensitive. He saw my face after we landed, approached, and said, “Iftach, your two bombs missed, but we stuck seven bomb loads out of eight in the bull’s-eye. As our commander, look at the final result. You should be proud.”

And again Raz recalled something: he produced the champagne bottle I had bought for the team after the operation. On it was written, in my handwriting, a mysterious mathematical formula that even Einstein couldn’t have grasped: “7/8=100%.”

All of us in the room laughed.

I knew some people thought I shouldn’t have flown that mission in the first place, and in hindsight they may be right. Some of them told me their opinion straight out. “High-ranking officers,” they proclaimed, “should manage, not fly.” There is some truth in that, but still I want to add something I didn’t say that evening. I had a friend from childhood, Daniel Vardon. He had personality for sure, and he also crawled into the enemy’s fire not once, but several times. Danny was decorated for heroism in battle not less than three times, the last of them after he was killed in the Six-Day War, when he tried to break through enemy fire to pull out wounded soldiers. He acted knowing his duty from inside, and doing without asking “What for?” and “How?” and “Why?” He didn’t pass the buck to others or bother his commanders with questions such as “Which way?” or “When?” or “Who?” I believe that even if there were radar screens in his time to sit behind and send others forward, he wouldn’t have used them. Danny was my example, and a reason for many things I have done in my life.

KAREN YADLIN SAT WITH folded legs on the table at the side of the room, among all the artifacts. Karen is also a character, and wanted to say something different, “to burst this heroic, happy macho bubble.” Her own secret began with the two-family house at Ramat-David housing. On one side the Yadlins lived, and on the other side the young family Ben Amitay.

Udi Ben Amitay was not there. One of the first F-16 pilots, he no doubt would have flown to Tammuz had he not been killed some six months before, in an aerial collision. Udi was the first loss in the new F-16 force. His widow, Esty, and their daughter, Maya, who was a just a newborn when he was killed, were there in the room.

Anyway, Karen, after asking for pardon from Esty and Maya, continued, “On January 20, 1981, I got home from work. In the parking place near our house I saw Spector’s big, black official car.”

What a mistake! I forgot Yak’s lesson from the War of Attrition that my official car should be kept out of family housing during daytime. I should have taken Ali’s red Beetle for that visit, but I didn’t. A few years later I made this mistake again: on my way back from Tel Aviv to Tel Nof, my last command post, I decided to visit Tali, Zorik’s widow and a very good friend. I drove my big, black official car into her parking lot without thinking about it. Her daughter, Ophir—yes, the same Ophir—happened to be home. She saw “Spector’s car” coming. When they opened the door I saw their faces. What an idiot I was! I should have parked two hundred meters away and walked to the house.

Anyway, back to Karen.

“I parked my car,” she continued, “but I couldn’t, just couldn’t, get out. I was in my ninth month. It was clear to me that it was either my husband or Esty’s. I won’t say what I prayed for.” Again she asked Esty’s pardon, and Esty nodded to her to go on. “Then suddenly Nahumi appeared from behind the house. He saw me sitting there and winked at me. So it was not Amos.

“There, for the first time,” concluded Karen, “I understood the burden of the ‘hero’s life.’ I realized that this way of life had its cost, that the risk was truly there. After three months”—and here her secret came out—“I squeezed out of Amos what all these preparations were about, what was the mission you were training for.”

Raz and I looked at each other, and then at Amos Yadlin. He kept quiet.

‡

I WAS VERY SURPRISED at the things coming out here. First Ofra Ivry, and now Karen Yadlin. Operation Opera had been top secret. Not just our lives were dependent on its strict confidentiality, but also the one chance to eliminate the nuclear threat to Israel.

The women had begun to talk, and I thought, “Uh-oh, what do these disclosures say about us?”

Читать дальше